Twenty-year-old Keltie Byrne was tidying up the pool area after the 1:30 p.m. show at Sealand of the Pacific in Victoria, B.C., when her rubber workboots skidded on the wet pool deck, sending her into the pool. As a dozen spectators watched, she tried to climb out. But the marine park’s orcas dragged her underwater. Despite being a competitive swimmer, Byrne had no chance against the persistent orcas Haida, Nootka and Tilikum. To the whales, unaccustomed to having trainers in the pool, Byrne was the most interactive toy they had ever played with. She resurfaced and cried for help twice. Ten minutes later, she surfaced again, but was still. She had drowned.

Twenty-year-old Keltie Byrne was tidying up the pool area after the 1:30 p.m. show at Sealand of the Pacific in Victoria, B.C., when her rubber workboots skidded on the wet pool deck, sending her into the pool. As a dozen spectators watched, she tried to climb out. But the marine park’s orcas dragged her underwater. Despite being a competitive swimmer, Byrne had no chance against the persistent orcas Haida, Nootka and Tilikum. To the whales, unaccustomed to having trainers in the pool, Byrne was the most interactive toy they had ever played with. She resurfaced and cried for help twice. Ten minutes later, she surfaced again, but was still. She had drowned.

On February 20, 1991, journalists wrote about the first person to be killed by orcas at a marine park. Barbara McClintock, then-Victoria bureau chief for The Province, arrived on the scene around 3:30 p.m. and gathered with other reporters in a parking lot overlooking the marina. From their lofty vantage point, they watched the recovery efforts and tried to piece together the story. At this stage, Sealand employees were dragging a weighted net along the bottom of the pool, trying to recover Byrne’s body from the whales, which kept it away from the crew for two hours. “You could see a ‘something,’” she says now, “which later you realized was a body.”

Unable to get closer to the action, the reporters had little to work with. No one could verify the story—even with witness accounts, the police were reluctant to release any particulars to journalists. The coverage of the accident was sparse at first, with details added as reporters gathered more information. No one knew how or why this had happened, and the shallow news items reflected that. McClintock’s vaguely worded article appeared in The Province the next day with the lede, “A whale trainer was dunked to death by three killer whales yesterday.” Police hadn’t even identified the trainer, and the story relied solely on one witness to provide any details or context of the accident. The result was a jarring 162-word article on the front page with the final line that read, “Then the whales became quiet.”

Over two decades later, Liam Casey recalls the enormous audience for “Inside Marineland,” the Toronto Star investigative series that was published in 2012. Casey’s colleague, Linda Diebel, wrote several stories in which eight whistleblowers claimed that Marineland failed to adequately care for its animals. Diebel, who spearheaded the investigation, made allegations claiming that Marineland’s water filtration system caused the animals serious health problems; dolphin skin fell off in chunks; Smooshi the walrus had an inflamed flipper, a chemical burn apparently caused by the water; six of seven seals were either blind or had serious eye problems; two aggressive belugas attacked and killed a baby beluga named Skoot. Later, Casey joined Diebel to pen an article that alleged Kiska the orca seemed lethargic and lonely in her concrete pen.

In addition to garnering widespread public interest, however, the series drew the ire of Marineland; its owner, John Holer; and Holer’s lawyers. Three months after two articles were published in 2013 about orders given to Marineland by the OSPCA to address problems first identified by the Star‘s investigation, Marineland sued the Star; in its statement of claim, Marineland denied the range of allegations in the Star series, saying its water filtration system is not substandard, nor are its animals neglected in any way. The Star stood by the allegations, and filed a statement of defence in response to Marineland’s lawsuit. The lawsuit was outstanding at time of publication.

Readers devoured the Star’s Marineland stories, which were part of a momentous shift in the way reporters cover animal issues. Today, animal-related journalism is becoming a blockbuster business, drawing a big audience and encouraging news outlets to devote scarce resources to the coverage, including more senior reporters. Thanks to the emergence of enterprising animal stories and high-profile documentaries, there is an acute awareness of animal welfare issues that didn’t exist a couple of decades ago. Interviews with reporters, experts and activists show that there is more serious interest in, and greater knowledge of, the problems animals face. But since the subject matter inevitably has soft and fluffy connotations, the animal beat still risks being perceived as less-than-serious journalism.

***

Our Five Favourite Canadian Animals

While the quality of animal journalism has improved dramatically over the past two decades, cute and cuddly still goes viral. Here are the stories behind five of the nation’s most popular critters.

Darwin

After running free in an Ikea parking lot dressed in a shearling coat, Darwin became a social media sensation in 2012. Last year, Yasmin Nakhuda gave up the legal battle for ownership of the Japanese macaque. He’s now in a sanctuary.

Lucy

Elephants need social interaction and Lucy, who has lived at the Edmonton Valley Zoo since 1977, is one of the few living alone in captivity in North America. Game show host Bob Barker has publicly called for Lucy’s relocation to a sanctuary.

Trevor

Yukon’s “death row dog” sparked controversy when a judge ordered him euthanized following a year-long court battle in 2012. The Whitehorse shelter Trevor had lived in considered him too dangerous after he bit several people.

Luna

After separating from his pod and becoming attached to the people of Nootka Sound, B.C., Luna starred in The Whale, a documentary produced and narrated by Ryan Reynolds about the animal’s life and tragic end.

Er Shun and Da Mao

News outlets have extensively covered these two zoo pandas since their arrival in 2013—from their China-to-Toronto voyage to their “bear-boganning” videos. Should their planned breeding succeed, expect to see even more of this panda family.

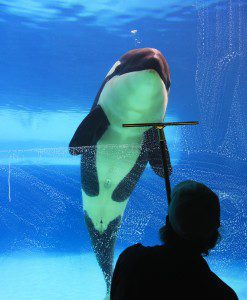

Tilikum, one of the whales involved in Byrne’s death, would help change the way journalists cover animal tragedies. The orca was moved to a new home at SeaWorld Orlando in 1992, almost one year after the incident with Byrne, and Sealand closed its doors forever by the end of that year. On a summer morning in 1999, trainers at SeaWorld Orlando found Tilikum with a nude body of a deceased male draped across his back. Canadian newspapers linked the man’s death to Byrne’s, and coverage included details that had been missing in the initial news reports about her death. In 2010, another trainer named Dawn Brancheau died in the pool with Tilikum.

This time, the coverage wouldn’t be so scattershot. After Brancheau was dragged underwater to her death, Tim Zimmermann, a correspondent at Outside magazine, wrote a 9,000-word feature that appeared in the July 2010 issue. Zimmermann’s “The Killer in the Pool” examined the 45-year history of keeping whales in captivity and the accidents that transpired in that time, focusing mainly on incidents involving Tilikum. Instead of simply recounting events, Zimmermann sought experts to explain how and why these types of incidents occurred. “If you want to try to get an inkling of what captivity means for a killer whale,” he wrote, “you first have to understand what their lives are like in the wild.” He pursued the most qualified sources, including Ken Balcomb, a marine biologist who had been tracking orcas for almost 35 years, and Don Goldsberry, who captured orcas for aquariums and notoriously hated reporters.

Zimmermann’s work had a depth of detail missing from much of the previous reporting. For example, he compared Sealand to McDonald’s and SeaWorld Orlando to a five-star restaurant, with its 220 acres of custom marine habitat. At SeaWorld, “there were seven different killer whale pools, including the enormous Shamu show pool, and seven million gallons of continuously filtered salt water kept at an orca-friendly temperature between 52 and 55 degrees [fahrenheit]. There was regular, world-class veterinary care. Even the food was a custom blend, made up of restaurant-quality herring, capelin and salmon.” Without having to look beyond this one magazine article, readers with no previous understanding of orcas could receive a close-up look at a controversial issue. Zimmermann provided enough depth and detail to allow his readers to draw their own conclusions.

Tilikum’s story would eventually find a wider audience beyond the magazine. After reading “The Killer in the Pool,” documentary filmmaker Gabriela Cowperthwaite started a project of her own—the 2013 film Blackfish, starring Tilikum, with Zimmermann billed as associate producer. After making a scant $2 million during its theatrical release in the summer, the documentary was viewed by nearly 21 million people when CNN aired it on television that October.

Blackfish became a rallying cry against the billion-dollar industry of marine parks. Since the film’s release, SeaWorld has published open letters criticizing the documentary’s claims that marine parks are harmful to orcas and refuting allegations that the park attempted to cover up facts about Brancheau’s death. A section of SeaWorld’s website is dedicated to arguing that Blackfish is propaganda. The documentary opened a Pandora’s box, prompting questions about the morality of keeping cetaceans in captivity.

After Blackfish made the rounds in Vancouver, National Post correspondent Tristin Hopper had an “icky” feeling about SeaWorld aquariums—and a news hook for a feature. Hopper reported that shortly after the documentary appeared on Netflix, supporters of the film converged on the Vancouver Aquarium in Stanley Park, rallying to get rid of the beluga whales kept there. Soon after, the Vancouver park board put an end to the breeding programs of most whales and dolphins at the aquarium.

This Blackfish effect was not the first time animal journalism had gone Hollywood. Grizzly Man (2005) told the grim story of a man who trusted grizzly bears too much; The Cove (2009) exposed the slaughter of thousands of dolphins in Japan; and Project Nim (2011) was about the attempt to break the barrier between human and chimpanzee. These documentaries are commercial productions made for entertainment, but after watching them, millions of people became knowledgeable on topics they might not be otherwise drawn to. Animal rights advocate Lesli Bisgould fought long and hard to convince reporters to cover stories about the issue. “It took a long time to get these ideas into the public consciousness,” she says. “But people have now seen these images that are too ugly to forget.”

***

Despite the attention that big stories attract, animal journalism still struggles to be taken seriously. Early in the 1990s, editors at The Vancouver Sun put out a call for new column ideas. Reporter Nicholas Read approached them with a concept close to his heart: a regular missive about animals and their welfare. To his great surprise, the Sun decided to give it a try. Read wanted to do something important, since he believed nobody was writing in a serious way about animal issues at that time.

His column, “The Ark,” ran once a week in the Sun beginning November 1, 1991. When John Cruickshank became editor-in-chief four years later, he reduced the column to biweekly appearances. In an email, he explains his thought process behind the cut. Cruickshank felt he needed to make the Sun look more serious in order to compete with The Globe and Mail. “I thought a pet column was kind of flakey. Readers told us they valued it. Live and learn,” says Cruickshank, who is now the publisher of the Toronto Star. Read now teaches journalism at Langara College in Vancouver, and he notes that many reporters’ mindsets regarding animal stories have changed: “People who run news organizations have recognized that they are popular, but they could and should be better.”

That popularity comes with a price—the internet is saturated with critter content that is neither newsworthy nor beneficial to the cause of animal welfare. Bisgould calls it a “chicken or the egg” situation, asking, “Is it the media’s fault for giving us these stories or is it our fault for eating them up?”

The problem isn’t just the steady stream of inconsequential cat photos. According to Casey, animal stories get covered by journalists because they are quick and easy to do, and there is an appetite for them.

In a news clip aired on CTV Calgary last September, a small black bear cub can be seen on a golf course with its mother and two other cubs lounging in the background. The reporter’s voice chimes in, “This oh-so-cute bear cub was caught on camera over the weekend trying to capture the flag at Mountainside Golf Course in Fairmont, B.C.” The cub grabs the flag pin and runs in circles before taking one of the golfer’s balls into the woods. It was, according to the reporter, “a front-row seat to a once-in-a-lifetime show.”

After the network aired the video, other news organizations followed suit and it went viral. CTV Calgary’s managing editor, Dawn Walton, says, “Every time there’s a bear in a tree, it’s always a top story local media covers.”

Eric Taylor, professor of zoology at the University of British Columbia, believes that “fluff” pieces such as the bear video trivialize wild animals and are not newsworthy. As the chair of the federal government’s Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, Taylor can’t find humour in the “fluff” until other important issues get the coverage, readership and action they deserve. Frivolous animal pieces serve primarily as entertainment and as a way to increase gate revenues at zoos.

There will always be coverage when a new exotic animal arrives at the zoo or when a newborn animal gets a name. Rob Laidlaw of Zoocheck Canada, an organization that works to protect wild animals and improve conditions in captivity, says these stories reinforce an idea that it is acceptable to treat animals like surrogate humans.

For others, including Michelle Cliffe, a communications officer for the International Fund for Animal Welfare, the upbeat animal story is a news item that people can relate to. “We are bombarded by bad news,” she says. “Sometimes you need those little things that connect you in a positive way.” The appeal may also lie in the opportunity to see animals that only exist in the wild.

***

Although no outlet appears to have dedicated reporters on the animal beat, news organizations have lately shown a willingness to put more resources into such coverage. Kim Elmslie, communications and advocacy manager for the Canadian Federation of Humane Societies, says journalists are taking more time to listen to animal welfare groups and understand complex issues. “When there was a trainer who came out with a series of accusations of things going on at Marineland,” she says, “the Toronto Star really seized that issue.”

In 2012, Diebel received information from a whistleblower claiming that something had gone seriously wrong the previous fall with the water at Marineland. After publishing multiple stories following months-long investigation, Casey, then on contract with the Star, joined Diebel in her 11-month investigation.

It was a major undertaking to convince Marineland employees to violate their confidentiality agreements and speak about the private, seemingly impenetrable company. Since Diebel and Casey published their multi-part investigative series and

ebook, three of the 15 whistleblowers have been sued by Marineland for defamation.

Elmslie says she was impressed by the articles and the depth of the journalists’ expertise. The investigation is a prime example of a news organization that was supportive enough to dedicate the funds and reporting resources to properly cover animal issues. In 20 years, Cruickshank has gone from cutting one paper’s animal column to funding months of full-time work by two reporters on a substantial investigation into animal welfare.

Despite the lawsuits, widespread scrutiny of orcas in captivity is finally making headway in Ontario. At the end of January, the provincial government announced plans to ban the acquisition and sale of orcas. The new rules include guidelines for tank sizes, bacteria content, noise and lighting, appropriate social groupings and other regulations for handling marine mammals. If Ontario passes the legislation, it will be the first province with specific standards for these animals.

Little did Casey know an assignment he received in 2011 as an intern would eventually contribute to more groundbreaking journalism. His editors at the Star sent him to Niagara Falls for a story in the summer of 2011. After a custody battle, a St. Catharines judge had recently ruled that Marineland’s captive orca Ikaika must be returned to SeaWorld Orlando.

“SeaWorld alleged that Ikaika had some mental health issues,” Casey laughs. “As a joke, they told me to go and see if he looked depressed.” Not knowing what a healthy or depressed whale looked like, he went to the courthouse in St. Catharines and pored over boxes of records from the case.

He found out that Ikaika was Tilikum’s son, and the story he wrote was a cautionary tale questioning whether Ikaika would cause any fatalities with his aggression, as his father had. Soon enough, both an investigation into Marineland and the story of Tilikum’s tragic life were engrained in the minds of millions.

These are just some of the many stories that have helped usher in a sea change in the quality of what once was shoddy reporting. The challenge now for Canadian journalism is to maintain the momentum toward influential animal stories. Maybe all it takes is a good, hard look at a warm and fuzzy subject.

A previous version of this story incorrectly stated that the OPSCA claimed Marineland failed to adequately care for its animals, and that both Liam Casey and Linda Diebel spearheaded the investigation into Marineland. It was, in fact, eight whistleblowers who made the claim. Casey joined the Star‘s investigation months after Diebel first began reporting on Marineland. The story also incorrectly stated that six sea lions—not seals—were blind or had eye problems. The Review regrets the errors.

About the author

Aimee was the head of research for the Review's 2015 masthead.