If you weren’t paying close attention, you might have mistaken the first four weeks of Doug Ford’s term as premier of Ontario for an extended stint on the campaign trail.

Though the province’s 26th premier was sworn in on June 29, the Conservative government’s relationship to the media was reminiscent of pre-election chaos for the duration of the legislature’s rare summer session, which ran from July 16 to August 14.

While ruminations on Ford’s similarities to another populist businessman-cum-politician south of the border have been floating around since before the election, other elements of Ford’s administration have garnered speculation that his political legacy might be running parallel to former prime minister Stephen Harper’s. Eight ex-Harper staff and MPs joined the Ontario PCs , including Ford’s campaign manager Kory Teneycke and communications director Melissa Lantsman, both of whom played key roles in the Harper government.

At the RRJ we’ve identified three thematic similarities between the Harper and Ford governments’ media strategies. Both restricted journalists’ access to officials in the government and maintained a distance from the press, showed limited transparency, and found new ways to control the narrative, establishing independent media operations.

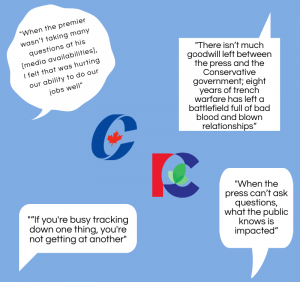

By the end of Harper’s term, his former chief media spokesperson Andrew McDougall said in a post on CBC’s website, “There isn’t much goodwill left between the press and the Conservative government; eight years of trench warfare has left a battlefield full of bad blood and blown relationships.”

Infographic: Alanna Rizza

During the summer session, it seemed as though the Ford administration was heading in a similar direction. One sticking point for many journalists in the first month of the new government was the restriction of questions and interference during press conferences. Journalists were often only allowed to ask four or five questions and were frequently cut off by clapping from Ford staffers.

Rob Ferguson, a political reporter for the Toronto Star and interim president of the Queen’s Park press gallery, confirms that the clapping seems to have stopped for now and that Ford is taking more questions from reporters.

Ferguson attributes the tensions during the summer sitting to a delayed transition out of the campaign trail mindset. “[The clapping] started during the campaign and it came over into the government,” Ferguson says. “I think the government realized that it wasn’t helping them.” Ferguson seems hopeful that the initial ‘Ford Fever’ has run its course after the House resumed earlier this month.

“I’ve heard from some Conservatives in the hallways that, ‘Hey, we’re a government now. We need to look like a government,’” he adds.

Other journalists, like Jessica Smith-Cross of QP Briefing, credit the improved access to journalists who raised concerns on social media.

“Several members from the press gallery publicized what was going on,” Smith-Cross says. “We took videos of the staffers clapping, which circulated on social media and then I think that had an impact on the decision from the government to change the approach with the clapping.”

Though these changes seem to bode well for future government-media interactions, Ford’s relationship with the media has been unusually restrictive from as early as April, when he made the unusual decision to forego a media bus on the campaign trail.

QP Briefing reporter David Hains tweeted that the PCs failing to provide a media bus would make it more difficult for journalists to ask Ford questions on a daily basis during the campaign.

Where reporters and officials interact is also key to building a routine relationship. Though most prime ministers use the National Press Theatre across from Parliament Hill for news conferences, Harper often refused to use this venue. According to the non-partisan outlet, FactsCan, he only made seven appearances at the theatre over his 10 years as prime minister.

Similarly, Ford’s Conservatives have shifted their use of the media studio in the legislature—where previous governments and the Opposition traditionally hold their press conferences—to holding all press conferences and media availabilities in the Ontario Room, located across the street from the main legislative building.

Both Harper and Ford also prefer to message their audience directly, investing energy and time into new media platforms.

In 2014 the Harper government launched its own information service, premiering a short-lived service called 24 Seven. These were promotional videos on the Conservative party’s website providing behind-the-scenes access to the former prime minister’s daily life (his cross-country travels and family outings, for example) while highlighting a bulk of Tory achievements.

When Doug Ford was on the campaign trail he created the Ford Nation Live platform to connect with voters. In July this year Doug Ford’s team extended this investment, which advertises PC party feats in the form of minute-long “broadcasts.” The videos often feature Lyndsey Vanstone, Ford’s deputy director of communications, interviewing the premier and his staff on issues including buck-a-beer and the Better Local Government Act.

Like 24 Seven, Ontario News Now is taxpayer-funded and blasted by critics as propaganda.

“In my time here, governments of all stripes have always put out itineraries for the premier,” Ferguson says, referencing past premiers such as Mike Harris and Dalton McGuinty. But media still doesn’t have reliable access to Ford’s daily activities, making coverage more difficult. “We tend to get a heads up when he’s doing an announcement, but we don’t really get a bigger sense of what he’s doing,” Ferguson says.

Smith-Cross says hiccups with media access are expected with changeovers in government, but when politicians don’t give reporters a chance to hold them accountable, it makes their job much harder.

“Right before everything kind of blew up with the clapping, when the premier wasn’t taking many questions at his [media availabilities], I felt that was hurting our ability to do our jobs well,” she says.

Expending more energy to get answers to basic questions also has the potential to distract journalists from digging deeper into the things they cover. “If you’re busy tracking down one thing, you’re not getting at another,” Ferguson says.

With files from Alexa Taylor