The former hierarchies of the journalism industry have crumbled by the weight of the digital realm, to be replaced by blurry parallel relations between journalists and readers.

The result is evident in the record 10,600 readers who participated in the Toronto Star‘s annual “You be the editor” survey. Administered by the Star’s public editor, Kathy English, the “highly unscientific, overly simplistic survey” served to provide insight into readers’ perspectives on the judgments made on to-publish-or-not-to-publish over the past year.

For example, 60 percent of readers voted that a cartoon presenting Toronto Mayor John Tory in bare-butt pants should have been published, which English now also agrees with. Fifty-five percent of the readers would have also made the decision to publish the Charlie Hebdo cartoons depicting the Prophet Muhammed. English disagrees: “it would be offensive and hurtful to Muslims in this community.”

Online journalism, in its many forms, has created a system of interaction that enables and encourages collaboration between reader and editor to discover, distribute and discuss the elements that create the best possible version of a news story. Today, the function of readers has surpassed that of being an audience, with technology fuelling their willingness to be heard and their capacity to be listened to, even on core matters of journalism ethics that the industry continues to debate.

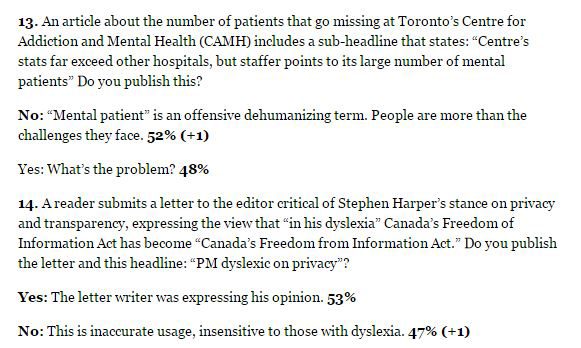

These include the examples English collated in her survey, especially those about issues relating to mental health stories, as shown in the image below.

“Neither of th[e]se references is in line with media best practices for writing about mental health,” writes English, “and, to my mind, neither should have been published in the Star.” I agree.

In fairness, English does recognize that “newsroom debate about what to publish is always deeper and more wide-ranging than what this light exercise in journalistic decision-making can depict.”

Yet in the digital age of journalism, what is considered good, thorough and balanced journalistic practice is often at odds with reader perceptions and expectations. That’s okay if journalists are aware that, while the hierarchy may have crumbled, they still make the final call on how to best tell the story to the reader, who can only play the role of editor. Survey results show that readers were aligned with the newsroom’s judgments in 12 of the 18 matters in question. I’m unsure what to conclude from that.

A day before the survey results were published, Mitch Potter, the Star’s foreign affairs writer, wrote how the decision to publish certain images of Syrian kids in conflict zones is important in defining whether the reader will perceive them with empathy or as furthering propaganda. “You, friends, are now the filter, every bit—if not more so—than those of us who used to be,” concludes Potter.

That’s a scary thought. The power of the reader is strong. The force of journalism needs to find a way to stay in line with, if not above, that.

About the author

Fatima Syed is the blog editor of the spring 2016 issue of the Ryerson Review of Journalism.