Tanya Talaga has been working at the Toronto Star for twenty years—first as a city reporter, covering breaking news around Toronto, then joining the national desk in the early 2000s. Today, she’s the Star’s Indigenous affairs correspondent.

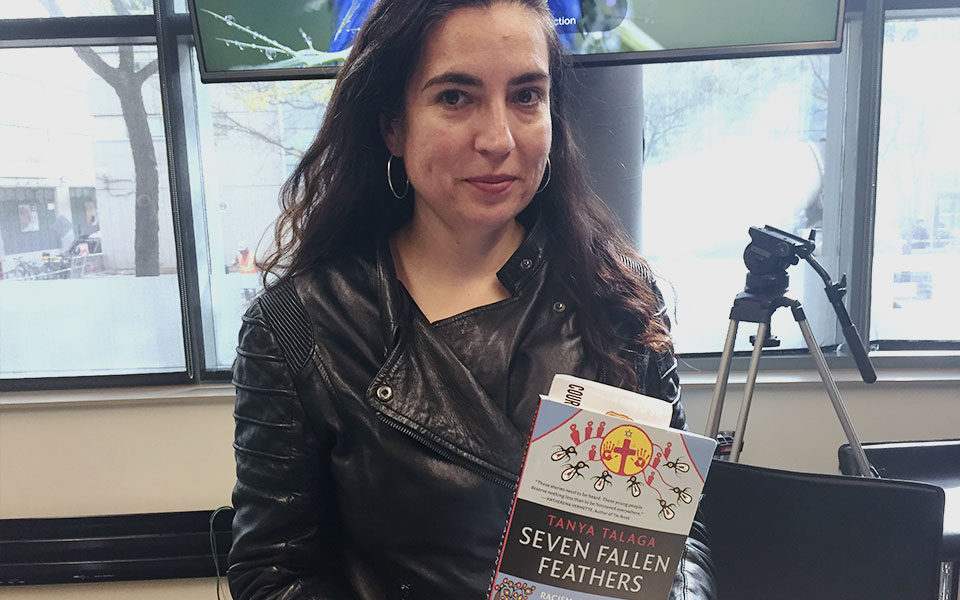

Her first book, Seven Fallen Feathers, published Sept. 30, looks into the unexplained deaths of seven First Nations youth in Thunder Bay, Ont. Five of the seven bodies were found from 2000 to 2011 within the rivers that run through and surround Thunder Bay. A 2016 inquest into the deaths ruled that three of the cases were accidental and the other four causes of death were undetermined.

In the book, Talaga looks into the complex legacy left behind by the residential school system and how it has shaped the city of Thunder Bay and the Northern communities that these children all came from. She’s been investigating the Thunder Bay deaths since 2011 and since its release, Seven Fallen Feathers has earned critical acclaim: It earned a finalist for the 2017 Hilary Weston Writers’ Trust Prize for Nonfiction.“There seems to be a lot of awakening as a result of her book…people are really paying close attention,” Former Regional Grand Chief of Ontario, Stan Beardy said.

Listen to Tanya Talaga read a selection from her book below.

How did you get into journalism?

I grew up in Toronto and I went to the University of Toronto… I was the news editor of the Varsity. I was part of Victoria College at the University of Toronto. I started at the Strand [Victoria College campus newspaper]. I volunteered and I just learned it. I went from there to the Varsity. It was a really, really good spot for me because I never went to journalism school.

Have you always been able to focus on Indigenous issues in your reporting?

There wasn’t a lot of appetite for Indigenous news in Canada, other than the stories on the chief that embezzles money. It was like that in Canada for a long time. It wasn’t until Idle No More and when the Truth and Reconciliation Commission came out that people started to have more of an appetite, and news organizations started to have more of an appetite for Indigenous news.

I think that the TRC really opened people’s eyes to this country’s history and the 94 calls to action really did mean something to people. All of a sudden the newsmakers, people that controlled the papers and the TV stations and radio stations, it was in their face. And part of the reason why… was probably [younger people that were] going up and tweeting, asking questions, creating their own space on Twitter and on Facebook. That helped move it.

In cases where a child has been killed or gone missing, how do you approach the situation as a reporter – how do you call that family?

It’s really hard. I’ve done it a lot. When I first started [with the Star] I was a city reporter and that sort of gives you the grounding and the basis to be able to do stuff like that often. So that, sadly [is] not a very good answer, but that kinda helps — but it doesn’t because you know it’s hard every time you have to do that. Every time you have to pick up the phone, you just never know.

In the north, I usually call somebody else first. Like a band council member or the chief of a community or somebody at NAN (Nishnawbe Aski Nation). I back into it so I’m not cold calling. It’s just better that way I think. You can be respectful that way and still get the story.

Do you think it’s true that Indigenous journalists bring a shared experience to their work that is unique to their lived history in Canada, accounting for systematic effects of colonization?

That’s very true. You have relatives that you never knew you had because they got taken away by Children’s Aid and then they’re showing up to family reunions. But you feel that weighed history. It’s a responsibility. It’s like when I was standing in Thunder Bay and realized – you gotta do it. You just have to [start writing about what’s happening to Indigenous youth from northern communities in Thunder Bay].

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

For more with Tanya Talaga, stay tuned for the Ryerson Review of Journalism’s Spring 2018 issue.