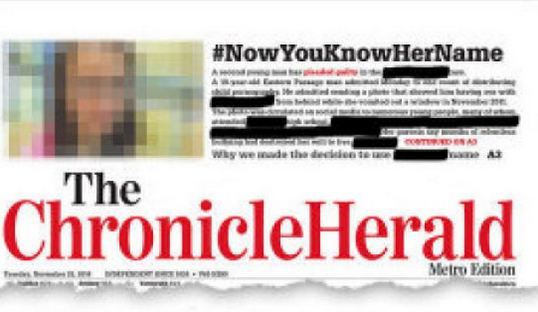

Nova Scotia’s The Chronicle Herald breaks the ban and publishes her name on November 24. Her father praises the Chronicle Herald for its decision and on Friday, he writes a passionate opinion piece on CBC.ca about his disdain for the lingering ban on his daughter’s name. For him, it’s about justice and opening up a conversation on sexual assault and cyber crimes by removing the gag that rendered his daughter silent, both in life and death.

The Chronicle Herald feels that it’s in the public interest to publish her name—it wants to accurately report the trial while enabling “free public debate over sexual consent and the other elements of her story.” In 2014, The Chronicle Herald, along with local CBC, CTV and Global affiliates, challenged the ban upheld by Judge Jamie S. Campbell which makes publication bans mandatory in all child pornography cases. “The issue isn’t whether I think the ban serves any purpose or makes any sense in the peculiar circumstances of this individual case,” writes Judge Campbell in his decision. He continues, “There is no discretion to be exercised. There is no provision that allows the judge to consider whether the imposition of the ban is in the public interest.”

Halifax police announce on November 25 that after receiving numerous complaints, they’re investigating a media organization for breaching the publication ban. To date, they’ve investigated seven cases where people have allegedly broken the ban; however, the Crown has yet to charge anyone. Chris Hansen, a spokeswoman for Nova Scotia’s Public Prosecution Service tells the Toronto Star that the Crown considers three factors when deciding whether to press charges: “the widespread publicity around the victim’s name, her parents’ wishes, and the judge’s own words on the purpose of the ban.”

Media lawyer Brian Rogers says that publications often inadvertently break bans. However, he’s worked on two cases where newspapers have intentionally breached them. For him, these are examples of publications deciding that there is a “greater public interest to be served.”

The Chronicle Herald refuses to remain silent. On November 25—a day after breaking the ban—it published an evocative editorial cartoon that shows the victim peering out from behind a mask. Huffington Post Canada led its homepage with an acrostic headline spelling out her name when a defendant in the case received a one-year conditional discharge after pleading guilty to charges of child pornography on November 13. People continue to share the hashtag #YouKnowHerName on Twitter and some frustrated Canadians are even tweeting out her name.

Her name may be [Redacted] in print and on air, but few journalists are remaining silent about sex crimes in Canada. A recent Toronto Star investigation led by Jayme Poisson and Emily Mathieu revealed that only nine out of 78 Canadian universities have a sexual assault policy and all 24 public colleges in Ontario lack one. Poisson and Mathieu share stories, photos and videos of real women who were violated and then neglected by academic institutions. Mere days after the investigation appeared, schools like Queen’s University and the University of Saskatchewan announced that they’re hastening the development of a comprehensive sexual assault policy for their students. The presidents of all 24 colleges also voted in favour of implementing similar policies.

Just as the ubiquity of a Nova Scotia teen is helping to shape Canada’s legislation around cyber-bullying, this exemplary piece of investigative journalism is positively changing public policy on university and college campuses. Yet, the coverage of this story pales in comparison to the one that’s resulted in charges laid against Jian Ghomeshi—arguably Canada’s biggest news story this year. In a National Post piece with the headline “I Knew About Jian Ghomeshi and never said anything. Am I complicit in his alleged abuse?” Slate’s Carl Wilson echoes many when he says that rumours of sleazy sexual behaviour circled Ghomeshi for years. While “everybody” knew, writes Wilson, no one did anything about it. Though the coverage is mostly reactive, it gains further legitimacy when alleged victims come forward and reveal their names to say that CBC’s wunderkind abused them.

People are becoming more aware of how prevalent sex crimes are in Canada. We know they’re largely ignored and underreported. Yet many of the stories written are reactive—only brought to light when a victim can be identified. Journalists can write story upon story on horrifying statistics, but for some reason it often takes a face and a name to make them feel real.

When discussing her case, she may be “a victim in a high-profile child pornography case.” Yet, people know her name, and now, some journalists aren’t afraid to use it. Canadians are talking about and engaging in discussions about consent, sexual assault and cyber crimes. “She used to say, ‘I love my name, but I can’t find it on anything!’” recounts her mother on Facebook. Now, in spite of a publication ban, her name—and legacy—is everywhere.

About the author

Amy was an online handling editor on the 2014-2015 masthead.