Tyler Brûlé and Andrew Tuck launched Monocle in 2007 as a global, general interest print magazine. Many people were skeptical of a magazine going against the tide–launching print in the alleged digital age. But Monocle’s circulation numbers continue to grow at a fast pace. “As circulations were in decline for a number of magazines, we just grew,” said Brûlé when speaking at Ryerson University on November 10. “Even through the darkest hours.”

The magazine’s success is linked to the idea that people in the digital age still want the tactile experience of a physical book or magazine. Tuck referred to the science behind reading, and the way reading in hard copy is an entirely different experience from reading something on a screen. He said it’s this tactile experience that we yearn for, as it’s something that breaks us away from the norm. “There’s a really magical moment where we relax and say, okay, the book isn’t going away, magazines are not going away,” said Tuck.

Tuck tied this idea into the return of the record player. He talked about people going to work and listening to digital tracks on their phones but then coming home and putting on a record. As the world becomes more and more digital, it awakens a new hunger for the exact opposite. Tuck said you can’t only live in one of these worlds, so while people today are constantly depending on technology, they still want aspects of the world without digital.

Brûlé and Tuck say that it’s especially young people who are seeking this escape from technology, this tactile experience. Brûlé said this pressure for magazines to go fully digital is mainly affecting older generations in the industry, who are afraid of looking out of touch and are trying to look current. But Brûlé said youth want a variety of experiences, and writing for print and reading magazines in print provides that opportunity for a tactile, more personal experience.

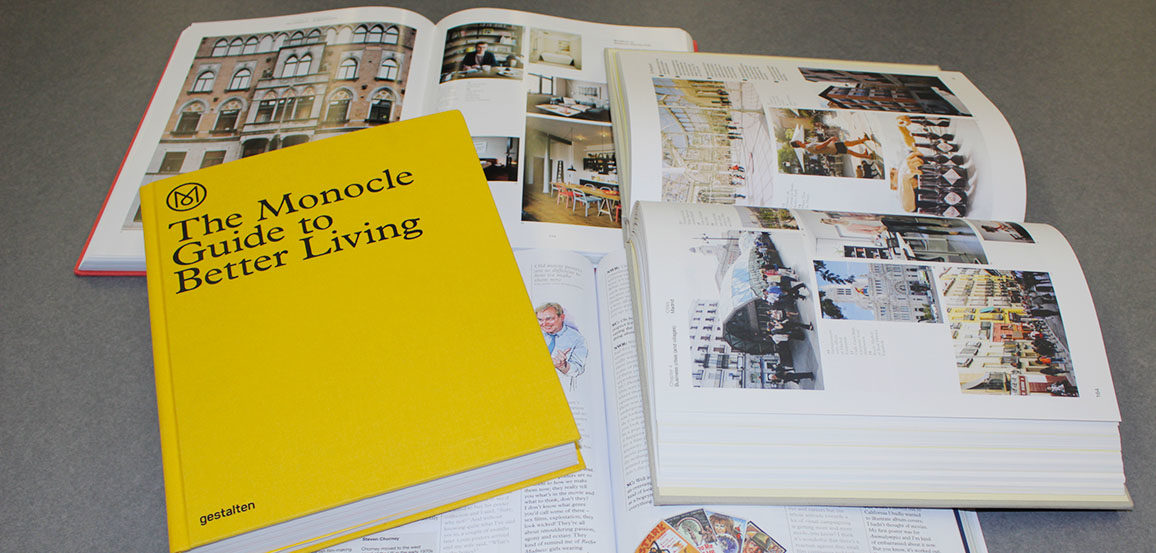

Though Monocle has a wide range of other elements in addition to print, such as travel books, cafes and conferences, it is not on social media. Brûlé and Tuck say this strategy is to form a deeper relationship with readers. “It doesn’t feel like we’re hiding away,” said Tuck. “For our audience, it doesn’t feel like the right fit.” While other magazines have Twitter accounts for readers to reach out and tweet at them, Tuck said this strategy usually doesn’t connect readers to the editors. At Monocle, there’s a genuine community, which is based on shaking people’s hands and forming a personal relationship.

“It’s quite amazing that we’ve all been seduced by the digital era,” said Brûlé. But the magazine knows there is no expiration date on print, that there’s still a need for print in today’s world. “Monocle is one of hundreds of brands that are beginning to understand that, and don’t believe that there’s a tsunami coming that’s going to wash us all away,” said Tuck. “We’re going to be here, we’re going to make money, we’re going to tell stories and we’re going to continue to surprise people.”

About the author

Sydney Hamilton is Head of Research on the Spring 2016 issue of the Ryerson Review of Journalism