Anya Zoledziowski sweats as she reads over her drafted email for what she thinks must be the hundredth time. She is a freelance journalist from Edmonton pitching her story, an in-depth look at how non-Black audiences should ethically consume hip-hop music, to the American publication Flood Magazine. The small voice in her head nags repeatedly, that the pitch won’t get accepted. She questions whether or not she is worthy of such an opportunity.

Still, Zoledziowski powers through and presses send. Days later, after a vicious period of constantly refreshing her inbox, she receives an acceptance for her pitch from Flood. She is in disbelief. Now there is a new hurdle to overcome: Zoledziowski worries if her work will be good enough to deliver to her editor. Again, she wonders whether she deserves the opportunity to write this piece.

This cycle repeats each time she pitches a new story to a publication.

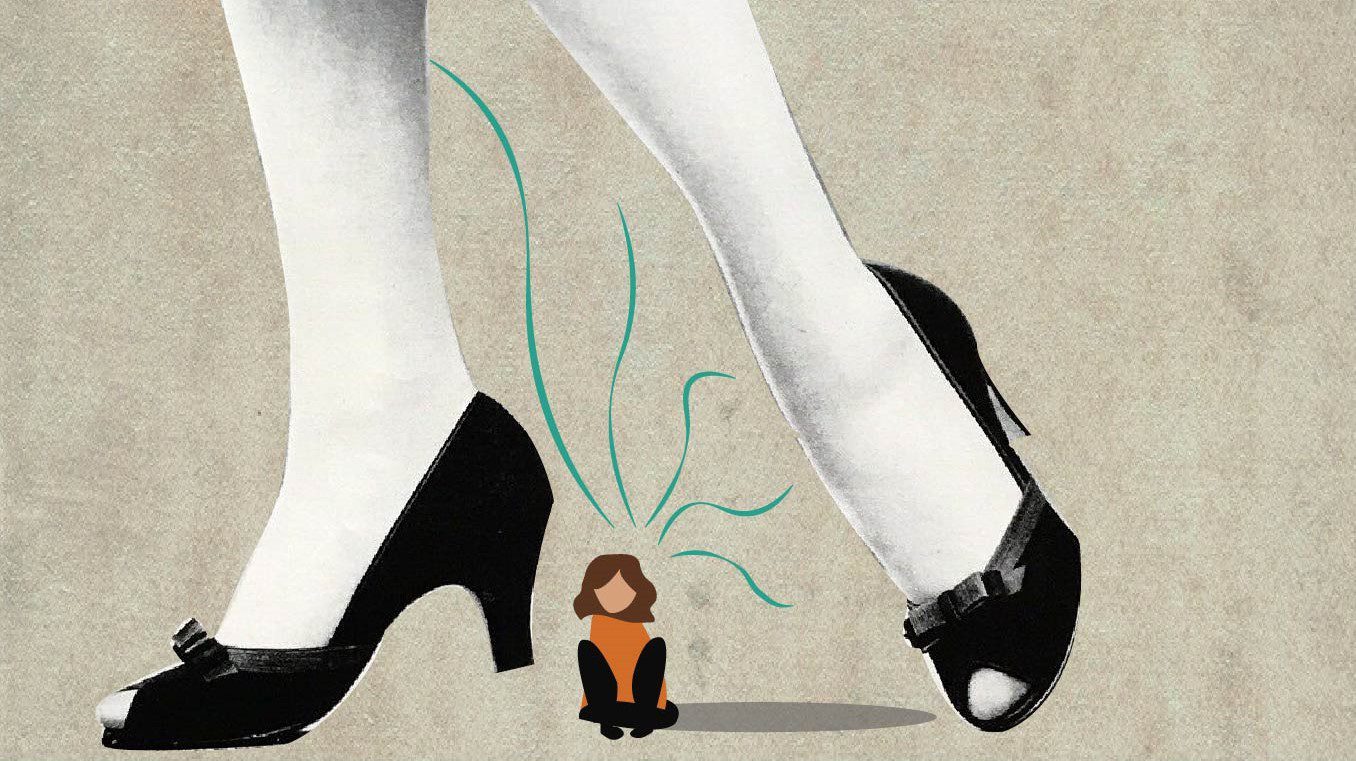

Zoledziowski is not alone in experiencing professional self-doubt. In 1978, psychologists Pauline R. Clance and Suzanne A. Imes coined the term “impostor phenomenon” to describe the “internal experience of intellectual phoniness.” In their study, Clance and Imes noted that this state of mind is more intense among a tested sample of high-achieving women, like those in law, anthropology, nursing, and teaching fields. In recent years the impostor phenomenon, now better known as impostor syndrome, has become a buzzword online, used by young professionals who fear they are undeserving of their successes.

A 2013 study examining the effects of impostor syndrome on minority undergraduates — including African-American, Latinx American, and Asian-American college students — found that racialized groups experienced high rates of impostor syndrome. Ethnic discrimination and a lack of representation contributed to feelings of self-doubt and placed a person at a higher risk of mental health issues, according to the study.

Zoledziowski says increasing competition in newsrooms can contribute to imposter syndrome. She also notes that intersectionality—a concept of complex discrimination based on converging social or political identities—can exasperate these experiences for women of colour in the newsroom. She identifies as a mixed-race person with Polish and Armenian roots.

“When you’re a racialized woman, you’re fighting against stereotypes associated with your skin colour, your hair texture, your accent, potentially, as well as your gender,” she says. With more hurdles to overcome, Zoledziowski says it becomes harder to remedy all of them, particularly in the workplace.

Shree Paradkar, a race and gender columnist at the Toronto Star, says she has experienced impostor syndrome in her professional career. When Paradkar returned to the Star after her maternity leave in 2011, she wanted to be promoted to the digital desk at the publication. Later on, she got the job and was even given the shift she preferred as an early morning page editor. Still, she didn’t feel worthy of this opportunity.

“I just believed it was a coincidence that I got it; that they had nobody else who could fill that and that’s why they gave it to me,” Paradkar says. She channelled her anxiety into her performance, believing she had to work twice as hard to prove herself.

Paradkar says this impostor syndrome comes from her experiences as both a woman and an immigrant from India working in Canadian newsrooms. “If I say one thing and a male says the same thing or a white woman says the same thing, that is noticed before what I’ve said is noticed,” she says. “That means I have to say that so much louder to be heard.”

Paradkar doesn’t feel impostor syndrome about her abilities now, because she knows how hard she had to fight for her current position but she still continues to face impostor syndrome on a personal level.. However, she still recognizes that there is work to be done—not just for her, but for the other racialized women in the industry.

“I’m very aware that as a brown person, yes, I’m racialized, but what I face is nothing compared to what black people face,” she says, based on what she’s observed. Instead of allowing these feelings to lessen her own experiences, Paradkar uses her platform to amplify black voices in media.

Shanon Lee, an activist against sexual violence and contributor for Forbes and the Washington Post, says as a Black woman working in the media sphere, she is no stranger to impostor syndrome.

Lee says she constantly reminds herself to “play big, not small” within her career in order to be seen. With this mentality, she says she often accepts opportunities she may not have initially wanted, just to ensure there is a Black woman in the room and that her perspective is heard. This way Lee can share her voice and experiences with those who may be unaware of the prejudice she and other Black women face.

“Sometimes the only reason why someone has a certain level of opportunities or visibility is because they have self-confidence,” Lee says. “They believe in themselves. They believe they should be there.”

Some women of colour do not experience impostor syndrome, like Karyn Pugliese, an Aboriginal Peoples Television Network (APTN) journalist and the National Director of the Canadian Association of Journalists (CAJ). She is of Algonquin-Italian descent and says that working in a space with other Indigenous women has made her feel more comfortable.

She says she has never experienced impostor syndrome in newsrooms because of the diversity in her workplaces and because her parents raised her to be confident.

“Whenever I got the job I always felt like I’m perfectly capable of doing this, and if I don’t know how to do it, I’m perfectly capable of figuring it out,” she says.

Pugliese also notes her experience is unique, because she spent most of her working life at APTN, where all her colleagues were also Indigenous. In mainstream newsrooms, women of colour may face a host of challenges.

“Outside APTN I’m very aware that it’s a different challenge being an Indigenous woman and getting your voice heard and being taken seriously,” she says.

There are ways to cope with impostor syndrome and conquer these feelings of inadequacy. Zoledziowski and Pugliese both suggest young journalists who experience impostor syndrome reach out to organizations and mentors to vent and discuss their feelings. Organizations like Canadian Journalists of Colour, Didihood, and the Canadian Association of Black Journalists have created spaces to facilitate this.

“Even if you’re just sharing stories and you’re just getting stuff off your chest, but you’re doing it in a really safe place, that’s really helpful,” Pugliese says.

For Paradkar, the key to overcoming impostor syndrome is to be okay with one’s mediocrity. “That doesn’t mean be mediocre, but accept the idea that sometimes you are not perfect,” she says. “Yes, you will make mistakes, that’s what humans do, move on.”

Correction: A previous version of this article stated that Anya Zoledziowski is from Toronto. Zoledziowski is from Edmonton. The RRJ regrets this error.

About the author

Sarah Do Couto is the co-chief copy editor at the Ryerson Review of Journalism. She is a Toronto-based writer interested in people, art, internet culture and all things taboo. Sarah is also the current editor-in-chief at Her Campus Ryerson and a self-proclaimed grammar nerd.