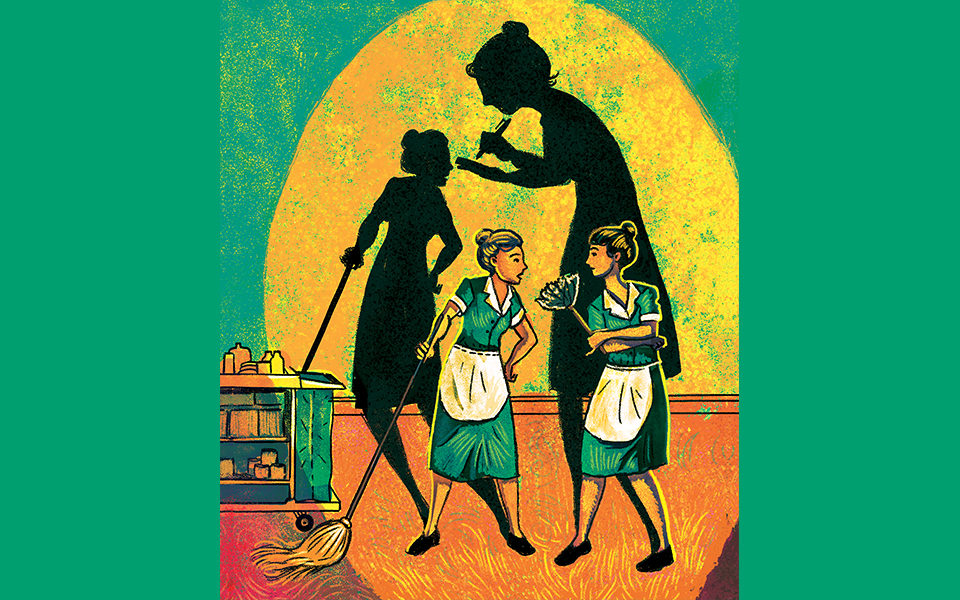

Toting pails, rags, cleaners, mops, and a vacuum, she walked into her third house of the day. Mopping her way through the sparsely-furnished foyer, she came to a halt at the pile on the floor. Upon scooping it up, it became clear the tenants had left it untouched for days until she, the maid, would come. The dog poop was dry and light.

“That’s the kind of detail that makes it come alive,” says Jan Wong, Globe and Mail veteran, award-winning journalist, bestselling author, and now associate professor of journalism at St. Thomas University in Fredericton, New Brunswick “I don’t think I would have gotten the detail if I had just tried to interview a whole bunch of maids.”

It started as a simple story about public policy and minimum wage: Could Canadians really live on $7.75 an hour? To find out, Wong immersed herself for one month back in 2006. She and her two sons moved into a $750-per-month basement apartment. Working for $9 an hour—though the math showed she was being paid far less—she successfully illustrated what it was like to live below the poverty line. They lived on cheap carbs (in 10 days, she dropped six pounds). And she worked crushing hours, scrubbing the toilets of Torontonians.

For Wong, her minimum wage series was uncharted territory. The Globe had not done many undercover stories, and she felt as though she was navigating an ethical “minefield” alone. “Generally speaking, you must be constantly aware of conflicts of interest, of rules, and of when to break those rules. It’s not something that can be carved in stone. A reporter must assess each circumstance each time,” says Wong.

The Canadian Association of Journalists’ ethical guidelines say reporters “may go undercover when it is in the public interest and the information is not obtainable any other way; in such cases, we openly explain this deception to the audience.” The question is not whether undercover journalism should be done, but how one can diminish sources’ feelings of betrayal or invasion of privacy; after all, journalists are sometimes immersing themselves in people’s lives for weeks or months.

As David Studer, CBC’s director of journalistic standards and practices, explains, the guidelines set out lofty principles. It’s left to journalists, their editors, and people like Studer to apply these principles during each new undercover project. Journalists navigating the murky ethics of undercover journalism are creating their own rules and reasoning—and coming to very different conclusions.

Of all the concerns plaguing undercover journalists, revealing personal information about unwitting subjects is one of the most pressing and perplexing. For his 2004 book, Down to This: Squalor and Splendour in a Big-City Shantytown, Shaughnessy Bishop-Stall dedicated a year to undercover immersion journalism. His book revealed deeply personal details about the squatters who lived in Toronto’s “Tent City”—filthy, garbage-filled, unused lakefront property, populated by homeless people. During his time immersed in Tent City, he created his own ethical rules to follow. One was telling subjects he trusted that he was writing a book, and they were a part of it. He would scribble into his notebook in front of them, or remind them that he was jotting down their conversations and actions when he was alone in his ramshackle hut. Of course, it’s not clear they really believed him. In a place like Tent City, many people are working toward their breakthrough—a novel, a screenplay, a memoir.

Before the book was published, he contacted his closest Tent City friends to ask if they wanted to use their real names. Bishop-Stall only included first names, but knew that those who knew the residents could likely still identify them from their descriptions. As part of the publishing process, he consulted with a legal team. They advised him to change the names of a few residents who had committed serious crimes, to protect himself against being subpoenaed in a potential lawsuit. No one that was contacted asked for a name change, but even now Bishop-Stall struggles with accepting their decision. He wrote that one source, Karen, smoked crack cocaine while pregnant. Eddie, another resident, told Bishop-Stall that he had been sexually abused at school. Changing their names might have offered a psychological softening they might have needed. Choosing to be completely transparent revealed the harsh reality of his subjects’ lives.

Not everyone will take kindly to the personal details that are included, and the results can be costly. Wong and the Globe were sued by the Nitsopoulos family for deceit and invasion of privacy after Wong described their Thornhill home, according to the Canadian Legal Information Institute. The Ontario Superior Court ordered the Globe to pay $9,160 in legal costs. The Globe also tacked an apology onto the end of one of Wong’s articles.

Kate Fillion, a former Maclean’s editor-at-large and author, went undercover early in her career, and wrestled with the question of how much to reveal about her involuntary subjects. In 1990, at the age of 25, she spent a total of three weeks over a two-month period observing life as a student in a Scarborough, Ontario high school—the cliques, the racism, the homework. Each teacher who taught her knew she was a journalist, and was aware that once she left high school for good, she’d write a Toronto Life feature about her stint. She felt particularly guilty criticizing Mr. Stevens, the pseudonym for a popular, respected and confident teacher, who she felt had given up on challenging his students.

Fillion went undercover to provide a first-hand perspective of high school through the eyes of a student, and in doing so brought awareness to the pitfalls of the Ontario education system. Her review of Stevens was swift and clear, leaving readers to come to a decision themselves: “Once he used an entire period to cut strips of paper with our names on them and pull them out of a bag to determine the date on which each student would deliver an oral presentation. Twice we’ve been given 35-minute tests on 10 vocabulary words.” She revealed that there are no safeguards for students who want to receive the highest education possible: “Curriculum guidelines and teaching credentials, for instance, provide zero protection from teachers who are lazy, untalented or just burnt out.” After spending a significant amount of time as a student, she knew he wouldn’t expect her tough observations.

Having the teachers of her classes know she was a journalist was a requirement demanded by the principal. However, this created a gap in anonymity among staff, and created the possibility of professional ramifications for Stevens. His subject, grade level, and detailed behaviours were all reported, making him easily identifiable by other staff members. This in turn could threaten his reputation and career. This was the reality Fillion had to accept.

Fillion let the principal read the final article. To her surprise, he didn’t ask for anything to be changed: “I think he wanted an objective observer’s opinion of his school for all the right reasons: curiosity, and the desire to make improvements where possible. I’m not sure he’d let a journalist in again, though.” She remembers him wondering how Stevens would react, but she never found out.

Al Tompkins, a journalist and teacher at the Poynter Institute, says revealing as much about sources as possible gives context for their actions and motivations. Wong’s writing included personal details about Maggie, the pseudonym for a maid featured prominently in Wong’s series. Having known Maggie, Wong says she would not have been pleased with the depiction of her obsessive need for perfection and her abusive marriage.

Stephen Ward, founding director of the Center for Journalism Ethics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, says that personal information about sources should only be revealed if it proves to be a pertinent element of the wrongdoing. This, for instance, might mean including private details about a source if a journalist is reporting on abuse. However, Ward adds that journalists should clearly state the private details act as evidence in the story.

Lisa Taylor, an assistant professor at the Ryerson School of Journalism, doesn’t support releasing personal information of subjects considered innocent. Some of the details in Wong’s piece were gratuitous, says Taylor, and had the “potential to hurt the people whose interest you’re supposed to be looking out for.” Hurting someone like Maggie, she says, can’t be justified because Maggie was an unsuspecting and blameless character. Contrariwise, Wong says that the personal details about Maggie became essential to reiterate that sedulous Canadian women were working brutal, low-paying jobs out of necessity—and to help readers relate to and respect them. “I tried to mitigate the invasiveness of the story, while still keeping compelling details so readers would engage with the issues,” says Wong. “So many people came up to me and said, ‘Hey, I will now always offer a cup of coffee to my housekeeper.’”

Sources and readers don’t always agree with journalists when weighing the potential harm to individuals and the public interest of a story. Bishop-Stall assumed there would be people featured in his book who wouldn’t like their depictions. There were a few physical altercations and threats of showing up to readings that never amounted to anything. Bishop-Stall set out to report a first-hand experience of Tent City, not to glorify or sugar-coat the people who live there. Bonnie, a tenant from Tent City, was “pissed off” when the book came out. Bishop-Stall attributes this to possibly being uncomfortable seeing herself through a different lens. Ethically speaking, subjects can’t edit the narrative or their past actions, but that doesn’t mean journalists should disregard a subject’s safety or psychological well-being. Bishop-Stall empathized with the people in his book; if the consequences of his writing weren’t ones he could live with, he’d take specific details out. In his case, he wrote the details first and thought of the implications during editing. “The whole point of going into places like these is that it is uncharted territory. You know, the whole point is you’re shining a light into corners that people don’t know about,” says Bishop-Stall. “You don’t even know what the ethical questions are until you’re inside them.”

And much of the fallout of what’s included in the book can’t always be predicted. “Ironically, most of the backlash was from people who weren’t even in the book,” says Bishop-Stall. “It’s never, ever, ever the people who you think are going to be upset by it.”

The Toronto Disaster Relief Committee was his strongest opponent. The committee had made a film on Tent City, Shelter From The Storm, released in 2002, and filmed in December 2001, which featured Karl, the “mayor” of Tent City, who Bishop-Stall describes as “a genuine neo-Nazi and one of the worst people I’ve ever known.” Bishop-Stall expressed no need to protect Karl, and his writing directly contradicted the committee’s portrayal. Cathy Crowe, co-founder of the committee and street nurse, says residents of Tent City felt betrayed and that his book damaged their chances of employment, schooling, and their family relationships. According to Crowe, one resident attempted to secure legal counsel. Crowe acknowledges and supports the benefits of undercover journalism, but she feels Bishop-Stall prioritized profits over ethical journalism by including many raw and private details.

Geoffrey Turnbull, a journalism instructor at the University of King’s College, in Halifax, says Bishop-Stall’s decision to offer name changes on an individual basis can be justified on an individual basis. Betraying the trust of someone who is acting in a harmful way toward the public, as Karl was toward Tent City residents, is not unethical. However, he adds, subjects that are faultless deserve to be sheltered from harm whenever possible.

Turnbull also says it’s important to recognize that Bishop-Stall dedicated a year of his life to immersion journalism. He didn’t live in a shack for a week and write what he saw. He lived all the dirty details: the unemployment cheques, the drug use, the rat infestations. Bishop-Stall had to keep these guidelines in mind all the while living in a dangerous place, where the struggle to survive could outweigh his moral compass. He grappled with doing the right thing, staying alive, and maintaining journalistic integrity.

The conclusions Bishop-Stall drew about whether people deserved privacy were not based on one or two encounters, but hundreds. In this way, undercover journalism can be more ethical because reporting decisions are based on a journalist’s comprehensive analysis of sources’ personalities and concerns.

Undeniably, how long journalists spend in the field is another ethical dilemma to consider prior to undercover work. If too short, they’re appearing to “slum it” for a story and they may not get the intricacies of the struggles people face, or why they act the way they do. But according to Tompkins, spending too much time risks them building the kind of trust that causes people to be overly vulnerable, and to feel incredibly betrayed when the story comes out. Taylor says a year would be enough time to provide a broad understanding, but it’s not feasible for most journalists or news organizations, she adds. There is simply not enough funding. Without that liberty, journalists may have to accept—and disclaim—that they aren’t providing a full picture if they choose to continue with an undercover story. To combat inherited privilege, Taylor suggests journalists focus the story entirely on the subjects, and omit personal reactions. Taylor adds that too many details make a subject more susceptible to recognition and embarrassment.

Hypothetically, creating a composite character would reduce the risk of a subject being exposed or uncomfortable while describing the details of a particular life. But that choice also carries ethical challenges. Wong shortens the time frame for immersion, or undercover journalism, saying anything less than a month of hard work is unacceptable. Her month working undercover as a maid gave her carpal tunnel syndrome, a side effect she still lives with to this day.

When journalists dip into the world of undercover immersion journalism, they have the potential to blur the line of editorial independence. Ward says undercover reporting is a balancing act between gathering enough information to initiate action and minimizing harm to citizens. The longer you spend immersed in a story, the more likely you are to get personally entangled.

Fillion thinks personal involvement comes with a price. She became a sympathetic listener to another student, a troubled teenager with a difficult home life and seemingly absent parents. When he confided in her, she became concerned about his safety and the risk of self-harm. “I found myself in an uncomfortable grey area where I could no longer pretend to be a teenager,” she says. She told him she was an adult and directed him toward counsellors, but lost his trust.

Feeling she had crossed the line as a journalist, she excluded him from the story. Retrospectively, she can’t think of another way she could have handled the confusing situation: “My job was to try to talk to the kids and find out about their lives, and this particular kid was so thrilled to have anyone listen.”

Bishop-Stall featured himself heavily in Down To This. His meticulous work was only made possible by becoming a Tent City dweller, and living the day-to-day life known by other tenants. Out of friendship and a sense of obligation, Bishop-Stall went to visit Jackie and others a few times after the book came out, but he eventually stopped. Fourteen years after his book’s publication, only a handful of the people he considered friends in Tent City are still alive. It became too hard to revisit that life, but it continues to have a lasting impression on Bishop-Stall. He still thinks—and talks—about it often.

Revealing the truth to sources is another major ethical conundrum that undercover journalists wrestle with. Coming clean, says Ward, isn’t necessary. When Wong left maid work, she left behind the maids, too. She never contacted Maggie again. Though she wanted to confide in her before the series ran, lawyers at the Globe advised against it, fearing an injunction that would halt publication.

When she left high school, Fillion told the teenagers she’d befriended that she wasn’t a student, but instead an adult who was checking things out. They never bothered to ask why or for what, or who she really was. Instead, they just found it “hilarious that [she] passed.”

Ward says a journalist doesn’t have any obligation to inform in advance, as long as the story has been done properly. Allowing a right of reply, he says, is only a good idea if including the response would boost the narrative, and doing so wouldn’t put publication in jeopardy. This changes person-to-person, and largely depends on moral blameworthiness. According to Ward, the ethical rules for how powerful and influential people are treated are different than those for ordinary citizens. If a journalist exposes and names someone powerful—the head of a corporation or a government official—giving a right to reply is ethically sufficient, says Ward.

Undercover journalists have a responsibility to the communities they infiltrate, says Turnbull. Their reporting should initiate public debate, and ideally, social or political change. It remains a personal decision whether to keep in touch and provide support for sources after publication. Wong says reporters aren’t social workers, instead their “contribution to society is illuminating problems.”

There’s no rulebook for undercover journalism. There’s no definitive guide that could be applied to every case. Every time, it’s the work of a journalist and an editor that answers the burning ethical questions that could break a story—and its subjects.

“Undercover can never be perceived as simply unethical or ethical. You have to see, well, what is the story, what are you doing. Why did you do this. It is a case-by-case basis,” says Wong. “I don’t think there is a template.”

In Disguise

Jan Wong, Kate Fillion and Stephen Ward choose their favourite undercover stories

One of Canada’s most illustrious journalists has a soft spot for the classics. Jan Wong says Ten Days in a Madhouse by Nellie Bly is one of her favourite undercover books. In the story, Bly is admitted to Blackwell’s Island Insane Asylum to expose abuse and neglect, unbeknownst to staff. Nickel and Dimed, by Barbara Ehrenreich, is another favourite. The book explores welfare and the working poor. Ehrenreich, much like Wong, presented herself as an unskilled woman looking for a job and trying to make ends meet.

Kate Fillion says there’s no contest. The 1961 book, Black Like Me, by John Howard Griffin, changed the course of her life. At 11 years old, she read Griffin’s tales of segregation in the Deep South, and it inspired her to major in Black American history in university.

Though controversial at the time, Stephen Ward always liked the undercover sting investigation known as the “Mirage Tavern.” The “Tavern” was a bar bought by the Chicago Sun-Times in 1977. They used it to investigate city officials who were shaking down local businesses and accepting bribes—all of which was documented on camera.

—Emma Bedbrook