What drives the Post Millennial is not journalistic principle but the old-fashioned grab for money and influence

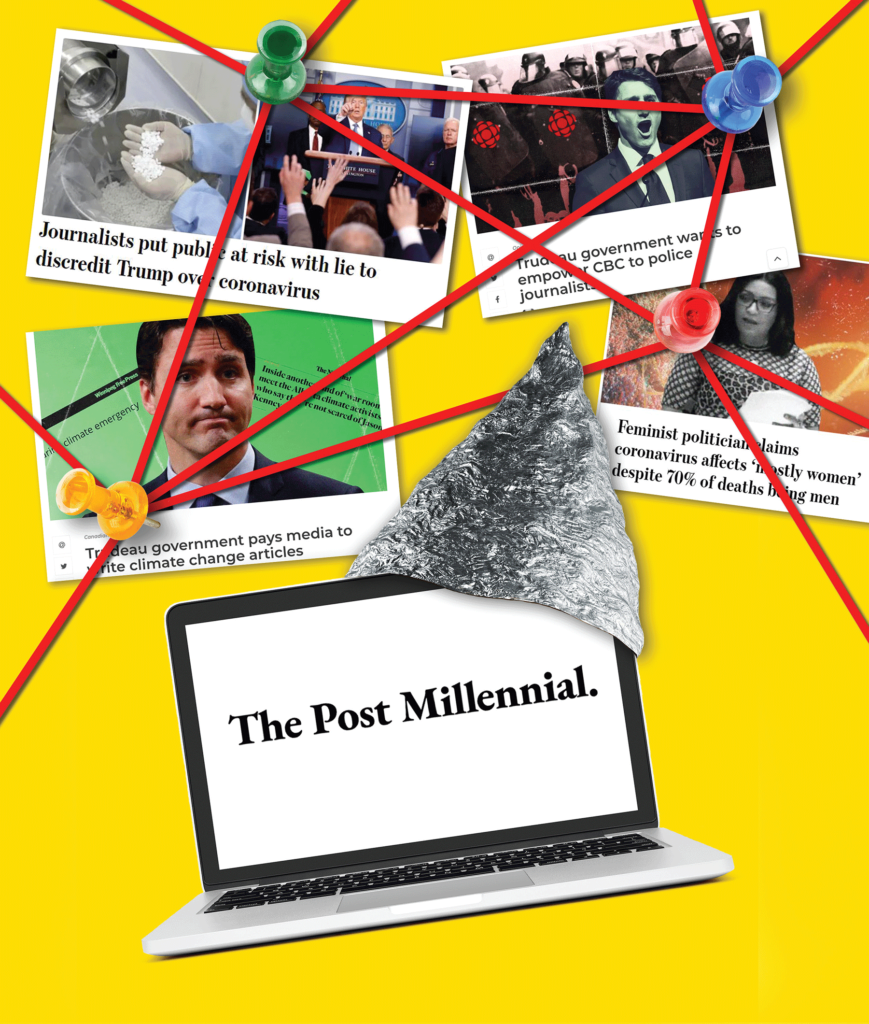

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”10″]I[/su_dropcap]t is shortly after 3 p.m. on August 22, 2019. The sun’s rays are streaming into the brick-red, open-concept space at the Centre for Social Innovation in Toronto, Emma McIntosh’s base of operations as a reporter for the National Observer. She is sipping a cup of coffee at her desk on the fourth floor when her phone begins to alert. It’s a mild tweet storm and McIntosh is, sort of, prepared. As the Observer’s misinformation and disinformation reporter, she’s used to seeing activity peak around political stories. But this seems different, personal. As she thumbs through her Twitter notifications, she sees traction building around her latest article (published earlier that morning) on the checkered ideological history of one of the Post Millennial’s senior editors. The publication responded to her story with one of its own, and the photograph that leads the piece is a doctored image of McIntosh. Someone has grabbed her headshot from the digital profile for her previous role as investigative reporter for the Star Calgary and photoshopped a tin foil hat onto her head. A cork board pinned with upside-down images, like the Illuminati symbol, has been superimposed behind her, the images on it connected with red string. The Post Millennial wants to get a message across to its readers: pay little attention to McIntosh’s writing—she’s a left-wing nut, a conspiracy theorist. The right-wing website is hitting back. After all, one of its editors is the focus of the Observer story, published as part of its Democracy and Integrity Project, which began during the run up to the 2019 Canadian federal elections, and continues to investigate “disinformation and the rise of hate.”

McIntosh’s piece ran with the headline: “He used to work for a site that promoted racists—now he edits a Canadian news outlet.” It centres on Cosmin Dzsurdzsa, at the time a senior editor at the Post Millennial, pointing out his past editorial affiliations: Free Bird Media, a website known for giving up digital real estate to commentary from far-right Canadian figures, and Russia Insider, a pro-Kremlin site. McIntosh also reports Dzsurdzsa’s former bio on the Post Millennial’s website states that he was previously a “researcher on the Oxford English Dictionary,” but found the dictionary’s publisher had “no record” of his employment.

The Post Millennial’s response is speedy. The publication’s then editor-in-chief Seyed Ali Taghva writes that McIntosh has written a “lazy, disingenuous guilt-by-association” hit piece; the Post Millennial hadn’t answered her questions because “none of her questions were worthy of response.” Taghva also writes that McIntosh’s article is “gross and unworthy of publication” because it attempts to deplatform Dzsurdzsa through his past associations. “The National Observer’s attempt to hit us was another swing and a miss by a left-leaning, pearl-clutching media outlet desperate to discredit us as we grow.” (Nowhere in his blistering attack on the National Observer did Taghva respond to the allegations about Dzsurdzsa’s employment status with the Oxford English Dictionary.)

McIntosh watched her Twitter account as the comments ballooned. Jonathan Kay, a former editor at The Walrus, whose mother Barbara Kay often writes for the Post Millennial, is cited in the website’s response to McIntosh. One of Kay’s tweets was embedded into the story. “Here’s a @NatObserver reporter writing in defence of antifa street thugs. We all oppose fascism. That doesn’t require us 2 support assholes who beat the crap out of reporters they dislike. Antifa is the worst possible advertisement for the anti-fascist cause,” Kay tweeted. One Post Millennial reader also emailed McIntosh calling her work “reprehensible” and “truly disgusting.”

“They want to send a message that if you criticize them, they will come after you,” says McIntosh. “This is not normal behaviour for a news outlet….I can see how, to a person who’s not versed in media, it can seem like a blow for blow.”

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”10″]E[/su_dropcap]mma McIntosh’s article followed a path laid out by a number of mainstream news organizations that have reported on the Post Millennial. Earlier that year, in June, CBC published an analysis: “Canadian news site blurs line between journalism and “conservative pamphleteering.” Later, in September, The Globe and Mail published reporters Robyn Doolittle and Greg McArthur’s investigation into connections between partisan network Ontario Proud and professional party fundraisers. In it, they unearthed a connection between Ontario Proud and the Post Millennial (they share a human resource—and strategist—in Jeff Ballingall). These articles were concerned with the growing use of the website to promote Conservative Party ideology and build public support against the Liberal Party (Kathleen Wynne, provincially, in 2018, and Justin Trudeau, federally, in 2019). The Post Millennial was the media arm of this exercise, a publication that presents as a journalism organization but follows few principles when it comes to reporting, writing, and disseminating factual stories.

Disinformation (the purposeful spread of false information) and its growth on digital platforms and websites is a significant issue impacting the practice of journalism today. In “Beyond Facts,” which was included in the November 2019 edition of the Columbia Journalism Review (CJR), devoted to the rise of disinformation and our response to it, editor Kyle Pope wrote that—in the American context—the upcoming presidential elections of 2020 will be “a contest that will be about a lot of things, no doubt including how and whether the traditional arsenal of journalism—accuracy, fairness, dedicated observation—is a match for the army of nonsense assembled against it.” He concluded, sadly, that in the fight put up by partisan propaganda and the world of social media trolls, “it looks to me like disinformation is winning.”

[su_quote cite=”Emma McIntosh”][The Post Millennial] wants to send a message that if you criticize them, they will come after you. This is not normal behaviour for a news outlet [/su_quote]

Pope’s concerns are about online warfare in relation to the landscape of U.S. politics, but the problems discussed in the CJR issue have a global reach. In a digital, borderless era, disinformation has become easier to spread, with numerous bad actors and public figures pushing their private agendas to massive audiences online. Coupled with the decline of local journalism—in the ten years between 2008 and 2018, many newspapers were either shut down permanently or were absorbed into existing newsrooms following a merger or acquisition—the growth of political platforms masking as news outlets is compromising the institution of journalism, as well as the ability of journalists to serve the public. Using the technology tools they have at their disposal, a wide range of actors—corporations, opportunists, and politicians—are able to spin the news in their favour, for political and/or financial gain.

Ontario premier Doug Ford helped legitimize this landscape in Ontario, as the Ryerson Review of Journalism reported in its Spring 2019 issue. His communications team denied interview requests from traditional news outlets. Reporters stationed at the provincial political headquarters, Queen’s Park, found themselves shut out. Instead, Ford bolstered his own platform, Ontario News Now, a partially taxpayer-funded Progressive Conservative Caucus website, that used “news’’ in its name, and hosted a communications executive. By the time Ford had completed his first year in office, he had appeared in more than 100 videos featured on Ontario News Now, according to an investigation by The Canadian Press. The vehicle allows the premier and his party to control the messaging presented on a public platform and spin the narrative in a favourable light, avoiding hard questions that journalists would ask. On Ontario News Now headlines read like promotional copy, pushing the premier’s initiatives without clear analysis. Case in point: “Ontario’s nuclear industry is a global leader in producing life-saving, cancer-fighting isotopes.”

Donald Trump’s upcoming presidential campaign is a prime example of how online news disinformation can have real world impacts. While researching his piece, “The Billion-Dollar Disinformation Campaign to Reelect the President,” for The Atlantic, staff writer McKay Coppins created a new Facebook account and liked the official pages of key influencers on the right: Donald Trump, Ann Coulter, and Fox Business, for example. The tech platform’s algorithm offered him some curated options based on his demonstrated interests. Coppins encountered headline after headline of false or misleading information promoting ideas that the campaign wanted to push into the public arena: like “Democrats are doing Putin’s bidding,” or “That’s right, the whistleblower’s own lawyer said ‘The coup has started…’”

“I was surprised by the effect it had on me,” writes Coppins. “I’d assumed that my skepticism and media literacy would inoculate me against such distortions. But I soon found myself reflexively questioning every headline.” His research led to his conclusion about “illiberal political leaders around the world.” Coppins says, “rather than shutting down dissenting voices, these leaders have learned to harness the democratizing power of social media for their own purposes—jamming the signals, sowing confusion. They no longer need to silence the dissident shouting in the streets; they can use a megaphone to drown him out. Scholars have a name for this: censorship through noise.”

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”10″]T[/su_dropcap]he spread of disinformation necessitates a network of operatives. In 2020, these operatives rely on occupying online space, running virtual production lines ripe with partisan content. In Canada, websites like the Post Millennial come under the scanner, drawing publications like the Globe, CBC, and the National Observer to investigate their legitimacy. Luring large audiences, they present readers with a hybrid mix of re-reporting and right-leaning propaganda. Collectively, they contribute to a culture of news disinformation by posing as legitimate journalistic organizations, despite poor practices, shady ethics, and concealed business models.

Established in 2017, the Post Millennial declared itself “Your reasonable alternative” to mainstream media. However, according to the online independent media outlet Media Bias/Fact Check, which classifies publication biases and deceptive news practices, the Post Millennial has a right-wing bias. It points to the Post Millennial’s use of inflationary headlines as deceptive. (Example: “HOT AIR: Trudeau’s climate hypocrisy will stall the green movement,” “HYPOCRISY: Alberta couple given tickets for walking on CN land while blockaders get free pass” and “Canada is broken because Justin Trudeau broke it,” all of which are tagged “Canadian News”).

I set out to do something similar to Coppins when I began to research the Post Millennial. I signed up as a reader in October 2019, dishing out $10 a month (it has now been raised to a $15 subscription tier) for access to its content, getting a pass into its members-only back end. I wanted to understand why readers were drawn to its work. I also wanted to know what I was paying for. What kind of content would I get in return for my contribution?

The Post Millennial says its goal is to “accurately and adequately report Canadian news events as they unfold and progress, and to share this reporting with as many Canadians and citizens of the world as possible,” according to its “About Us” page. The website is visited an average of about two million times each month, according to SimilarWeb, a website analysis tool.

Of the two men who founded the website, one—the editor who penned the piece on McIntosh, Seyed Ali Taghva—is no longer there. The other, Matthew Azrieli, is its chief executive officer. Neither have an academic connection to journalism. They met through a mutual friend who knew they wanted to start their own digital news media outlets. Taghva, 24, a self-proclaimed entrepreneur, and McGill University labour and industrial relations student, met Azrieli, a Berklee College of Music graduate with a degree in songwriting, in Montreal over lunch at a Korean restaurant to discuss their personal and professional ambitions with one another, according to Taghva. “I didn’t know anything about Matthew at the time,” recalls Taghva. “He told me his family built houses. I told him mine did too, not realizing the difference.”

It turns out Azrieli’s family had built quite a few houses. His grandfather, the late David Azrieli, was an Israeli-Canadian real estate tycoon and philanthropist. In 2015, the Azrielis were Canada’s 13th wealthiest family, with their net worth an estimated $5.83 billion, according to Canadian Business. The duo thought they could employ their diversity and combination to good effect. Both consider themselves immigrants: Taghva an Iranian Muslim and Azrieli being what Taghva calls “a mega-Jew.” Collectively they could develop a “pro-diversity, pro-small market organization” to dominate this space.

It sounds potentially sinister but the master plan might have been a little haphazard.

Azrieli had already purchased the domain name ThePostMillennial.com so they decided to go with that as their name. Azrieli purchased the domain because he had “joked around” with his then girlfriend, now wife, about owning a media property. “I found the idea of me getting involved with media to be innately funny for some reason, and that’s what inspired me to try getting into it,” he says.

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”10″]T[/su_dropcap]hese website mavens don’t consider themselves journalists, that much is clear. But how would they enter this space and prove their legitimacy? In its piece on the Post Millennial, CBC put the microscope, among other things, on the website’s ethics page. Read independently, this seems sound. It outlines the policies on how to report on sexual assault, general ethical guidelines, and equipment renting. The terms, it turns out, were mostly a mish-mash of guidelines copied directly off the websites of four prominent legacy publications: The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Globe and Mail and the Toronto Star.

But copying—through a cut and paste job—isn’t the extent of the concern. The publication’s ties to platforms like Ontario Proud and Canada Proud (platforms marketing conservative ideas that were founded by the Post Millennial’s chief marketing officer, Jeff Ballingall), are too. That connection alerted Craig Silverman, a BuzzFeed News journalist, who has spent several years documenting the rise of misinformation and fake news in the digital sphere. Ontario Proud was credited by outlets like CBC and Toronto Life for helping Doug Ford’s political win. Both platforms receive funding from private investors.

“There isn’t an example where I can think of in the past where something that describes itself as news organization has a direct link to an overtly political distribution network, where they have shared executives, and where the financial success of that newsroom is really dependent on producing material that generates appeal for that partisan network,” says Silverman.

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”10″]A[/su_dropcap] team of seven core researchers at Ryerson University have been at work collecting and analyzing data for a project called “Digital Archetypes of the Canadian Right.” By analyzing the way right-wing media platforms covered the 2019 federal election, the team has dissected the readership of websites like the Post Millennial, and the impact of their content on those who come across it.

Right-wing news media platforms like the Post Millennial are not a new phenomenon. But experts like Melody Devries, a researcher and digital ethnographer for the Digital Archetypes project at the Infoscape Research Lab at Ryerson University, worry that they are impacting the already fragile credibility of media organizations by posing as partisan news outlets. This means the Post Millennial works to get a clear, political point across and influence the actions and beliefs of its readers, says Devries. “When you look at all of their articles, you can gain an idea of who not to like from that article,” she says. Her work mainly consists of the analysis and archetypal characterization of the social media profiles of those sharing right-wing media links.

There is a distinction between endorsing candidates, as mainstream partisan media publications have typically done, and pushing a political agenda. They also cover other candidates in a way that is not quite so emotionally spun as, say, the Post Millennial’s harping reportage around Trudeau, says Devries. This is proven through how the Post Millennial chooses to cover and frame stories, she notes. Devries gives the example of a hypothetical right-wing-organized rally which becomes violent. The Post Millennial, she says, may, despite their use of neutral language, choose to frame the story by saying a left-wing “social justice warrior,” (or SJW as it is commonly referred to online) was equally, if not more, violent. It gets a political message out, she says, that the social justice warrior is the problem. This is because, while traditional conservatives engage with and share online content, a neoconservative “is likely to engage with the content more, chew it up and spit out its arguments in a way that is meant to conceal how far right it is,” says Devries. “A lot of the Post Millennial articles as well, they infer racial politics while not actually talking about it,” she says. They do this through publishing stories about topics, like Don Cherry’s firing from Hockey Night in Canada last year following his comment about how Canadian immigrants (whom he referred to as “you people”) do not wear poppies. However, in these articles, the Post Millennial will sneak in ideas about Canadian identity and Canadian pride. “These are coded words for white Canadian,” she says. This includes an opinion article published in October titled, “A response to Don Cherry’s firing from a daughter of immigrants,” in which the author says her white Polish-immigrant parents proudly wear their poppies every year, and that those upset by Cherry’s “you people” comment, are people who will “search for any minuscule thing to be outraged about so they can shut down anyone that doesn’t follow their PC rules.”

[su_quote cite=”Pat Perkel”]There’s a difference between being partisan in your opinion and in your editorial standing and your view of the community, as opposed to your news [/su_quote]

These ideas and stories by the Post Millennial and other platforms like it are often found online in Facebook groups like that of the Yellow Vest movement. The movement, which originally began in Canada as protests against a federal carbon tax and Canada’s involvement with the United Nations (UN), has since included vocal sentiments around immigration.

Last January CityNews shared a video of a self-proclaimed white nationalist, wearing her yellow vest over a black ‘White Lives Matter’ T-shirt, at an Alberta rally. The woman, when confronted by the reporter about the mixed messages and racism within the Yellow Vest movement, responds confidently, “Yeah, absolutely, I’m a white nationalist in their movement.” When asked again how she thinks other Yellow Vesters feel, the anonymous woman shrugs and shakes her dyed red ponytail beneath her brown ball cap. “They don’t really seem to mind,” she says.

Still, the “Digital Archetypes of the Canadian Right” team concluded that while media groups like the Post Millennial and others did not influence the election outcome as was the case with similar groups in the U.S., they still influence the spread of violent far-right ideologies. The conclusion was clear, says Devries: The Post Millennial is “an insidious product of contemporary reframing of far-right ideas.”

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”10″]F[/su_dropcap]or Azrieli and Taghva, launching the Post Millennial was also a business opportunity. The two had identified a gap in the news production market: the absence of a flourishing right-wing media content hub. “On the centre-left there’s a media company at every standard deviation,” Taghva says. “On the right, it’s sort of like nothing, nothing, nothing, nothing, Fox News. Then nothing again, then Breitbart.” (Taghva ignores the presence of a range of existing right-wing publications like Rebel, Toronto Sun, and the National Post). He continues, “The one place in the media industry that’s just completely nonexistent, where companies don’t exist, is the real centre-right. There’s this giant media market opportunity that no one’s really talking about.”

The Post Millennial isn’t transparent about its funding. Azrieli says none of his family’s money is invested in the website, and that revenue comes from subscriber contributions, ad revenue, and “private investors.” (They won’t reveal the names of those investors.)

Fenwick McKelvey, a professor at Concordia University who specializes in algorithmic media and communication, says websites like the Post Millennial are gaining ground and financial success in part due to a polarizing media environment in Canada. Because right-wing websites function more on emotional triggers, they have a recognizable rhetoric and may vilify opponents in order to publish online hate and spin in an unprecedented way. This, he says, “becomes a means to outrage its audiences and channel that emotion into donations.” The approach serves two functions, says McKelvey: creating a ripe advertising climate for financial gain, and pushing a conservative political agenda. These websites have come to recognize that by effectively creating things that look like stories, they can build a sustainable advertising-based business model.

Anthony Burton, who along with Devries is a researcher at Ryerson’s Infoscape Lab, is concerned about how emotional approaches to online content are used to garner clicks (and therefore advertiser dollars) online.

Burton believes that websites like the Post Millennial establish dangerous practices through their approach to online content. “[They’re] engaged in the capitalization of news and making a product that is directly engaging with social media reaction…to make money. There is this deeper fundamentals of journalism—and truth—[question] that we believe in as a society. That’s getting violated and it’s all in the name of making a few quick bucks or riling someone up.”

Azrieli and Taghva owe some of their success to the collapse of the local media market in Canada. This market gap provided an opportunity. “Some of the biggest stories we write are weather articles,” says Azrieli. This is driving large populations of rural communities, for example from Alberta and Saskatchewan, to the website. “There are towns in Alberta where 30 or 40 percent of the population are viewing us every month,” adds Taghva.

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”10″]J[/su_dropcap]ournalism, as a profession, isn’t regulated. Nothing like the Institute for Chartered Accountants exists as it does for chartered accountants. Nor anything like the Canadian Bar Association as there is for lawyers. But the industry deals with ethical and other problems either individually through in-house public editors, like Kathy English at the Toronto Star and Sylvia Stead at the Globe, or externally through a membership-based organization called the National News Media Council (NNMC). The NNMC has more than 500 members but the Post Millennial is not on that list. As a third-party ethics body, the NNMC rules on complaints about journalistic practice and publishing, publishing decisions based on complaints filed with it. Despite not having membership status, readers have filed complaints against the Post Millennial. One complaint arose when the website reported the RCMP has taken definite action against the Liberal government over the handling of the SNC-Lavalin scandal. This, it turned out, wasn’t true. The mistake has since been amended, though, unlike other media organizations, the Post Millennial made no correction note or retraction of its earlier statement.

Brent Jolly and Pat Perkel of NNMC say since we are in an increasingly polarized political climate, it is even more important to hold those claiming to be journalists to account, and not act on hidden agendas. “There’s a difference between being partisan in your opinion and in your editorial standing and your view of the community, as opposed to your news,” says Perkel. “Understanding ethics is something much more than just posting it. It’s about internalizing what it actually means and actually holding yourself to those standards,” says Jolly.

It also means being responsive when you’re caught out. Silverman was at work in his BuzzFeed office last year when he came across a problematic Post Millennial headline: “Reports of shots fired in Manitoba as police search for manhunt suspects.”

Silverman, who tracks fake or misleading stories, came across this one and began to investigate. No other news publication or local law enforcement had reported anything about shots being fired. Following his practice of informing the public on Twitter about a case of misinformation, he tweeted: “You can see how The Post Millennial quickly pushed its story out via big large network of FB pages it and its staffers control. In this case, people were misinformed.” Those large social media networks included Ontario Proud.

“It really seemed like this was something that had been rumoured in the early stages of what was going on, but had not panned out at all,” says Silverman. As was the case with McIntosh’s piece, Taghva’s response was quick. Silverman says Taghva tweeted a defence of the article, citing Spencer Fernando as another website that had reported the same news. But, Spencer Fernando, like the Post Millennial, is another right-wing website that claims to do journalism. The Post Millennial also embedded a Global News video into the article, which claims a potential sighting of the suspects. Taghva later deleted his tweets.

When I met up with him in November, I asked Taghva about this online conversation over tea at a Persian cafe in Richmond Hill. “Honestly, fuck Craig Silverman,” he told me. “He’s lying. We did adjust it and the article was changed,” he says. “We quoted a journalist from Global News on the ground saying what she heard from people.”

[su_quote cite=”Melody Devries”]When people start assuming these types of news sites are valid as sources of information, then that’s one step in the slippery slope to believing more conspiracy theories [/su_quote]

In fact, the Post Millennial didn’t alter the most relevant viral part of the article: the headline, which remains online, a documentation of its misinformation about the shootout. (The Global News citation Taghva mentioned is incorrect.)

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”10″]T[/su_dropcap]he thing is, the Post Millennial does have an audience.

It emerged out of a sense of rejection or isolation from the mainstream media, asserts McKelvey. “Certain viewpoints are not well represented….There’s a liberal media bias.” Because many right-wing political perspectives are not represented in mainstream media, the barrier for entry into the space is lower, he says, making room for players to abuse the space through poor journalistic practices.

Patrick Lane, a 55-year-old hotel and restaurant manager of the Bayshore Inn Resort & Spa, is a proud consumer of the Post Millennial. On an overcast May day in 2019 following unrelenting showers, the usually-vibrant blue lakes of Waterton Lakes National Park, Alberta, appear faded. Inside the hotel, which occupies a prominent lake-facing spot at the edge of Waterton Avenue, the gloomy mood carries over into the kitchens of the establishment.

Lane and his team are digesting information about the federal (Liberal) government’s announcement of a $595 million media bailout package to help support struggling news organizations in Canada. Lane is disgusted. “Are they going to bite the hand that feeds them?” He asks about the news media which will receive bailout funding. A Conservative, he is nervous about the future of news in the country. He is already skeptical of government funded news organizations like CBC.

Lane says he feels like he is living in a dystopian world, akin to George Orwell’s 1984. In this dystopia, Trudeau and the Liberals are the problem. One of his employees from mainland China assures Lane he’s on the right track: this is the beginning of state-controlled media, not unlike the power exercised by the Chinese government.

Since the bailout was announced, Lane’s trust in websites like the Post Millennial has only increased, especially since it wasn’t on the list of recipients. Other Post Millennial readers with whom I spoke share Lane’s views. Like Heather Hauka, a 40-year-old nurse and single mother, who bemoans the loss of neutrality in news and is also suspicious of CBC’s leanings. “[It] feels like these days we don’t have the option to tune into any kind of neutral news reporting because it doesn’t exist.”

While she would prefer unbiased reporting, Hauka isn’t sure that is humanly possible. “The next best thing,” she says, “is to be clear about what angle you’re representing and then let people filter through what you’re saying based on that.” She started reading the Post Millennial a year ago. Along with Lane, she believes the Post Millennial can be trusted to give accurate, often right-positioned, news.

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”10″]S[/su_dropcap]ites like the Post Millennial can be “stepping stones” for Conservatives and those who are apolitical, into believing further right and more extreme conservative rhetoric. “When people start assuming these types of news sites are valid as sources of information, then that’s one step in the slippery slope to believing more conspiracy theories,” says Devries.

The growth of such ideas concerns Evan Balgord, the executive director of the Canadian Anti-Hate Network, a non-profit organization which researches and reports on online hate groups. Right-wing adversarial websites like the Post Millennial contribute to a kind of open hatred, he says. “It’s not like somebody reads an article from the Post Millennial and goes out and assaults somebody, that’s not how it works,” he says. “There’s an entire ecosystem that basically feeds the same lie over and over again, because hate groups could not exist without conspiratorial thinking.”

“There’s outlets that feed these conspiracies and feed this hatred of ‘the other,’ and their effects are more diluted than a direct cause and effect. They play on an ecosystem where someone will get radicalized by consuming a variety of media within that ecosystem, and then may go out and do something about it,” says Balgord. This is especially prevalent in the comment sections of websites like the Post Millennial, where you can visibly see the kinds of feelings stirred up by these articles, he notes. For example, in the Facebook comment section of the Post Millennial’s story “Woke Twitter claims it’s racist to call coronavirus ‘Wuhan virus,’” one user commented, “Why are the ‘woke’ so apparently braindead? Asking for a friend,” while another wrote “I’ve been calling it the Kung Flu. Is that ok?” Another fan responded to this comment “fru not flu.”

Other posts like “WATCH: International Women’s Day protestors accidentally firebomb themselves after trying to burn Mexico’s National Palace,” commenters wrote, “They missed the kitchen?” and “Sending a woman to do a man’s job.”

While it is not impossible for journalists to be activists, they must always be journalists first, says Perkel, the executive director of the NNMC. Journalism, according to her, is about the age old motto of holding the feet of those in power to the fire. But it’s hard to do when you are advocating for a specific cause for the purpose of monetary gain.

When I met with Taghva in November 2019, he told me he was a lifer at the Post Millennial. “It’s hard to see me leaving. It would have to be at a very nice premium for my time,” he says, referring to if someone were to buy his company shares. In January, Taghva resigned from his position as editor-in-chief of the Post Millennial. A month later, he accepted a position as Managing Director of Digital Media at ZeUCrypto, where he promotes an encrypted email service called Mula, which he says is a “tool to take back control of your personal data.”

Earlier, he had told me his critics are actually just jealous of his own growing business success. “Everyone who says my team isn’t made up of journalists can go fuck themselves. This exclusive idea of what it means to be a journalist, I don’t adhere to,” he says. Instead he describes the Post Millennial as “a bunch of hooligans in Montreal getting wasted and writing intense articles.”

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”10″]T[/su_dropcap]he Observer reporter who was at the receiving end of Taghva’s temporary wrath, doesn’t buy this idea. “No one who is a reporter is writing advocacy pieces,” says McIntosh. “I think there’s some crucial firewalls that don’t exist.”

“They’ll attribute themselves to being young and learning, and it doesn’t make it any less wrong,” she says. “You can’t be like, ‘Oh, sorry, we’re getting our shit together.’ It doesn’t work that way when you’re a real journalist. Things have real consequences.”

About the author

Sarah Do Couto is the co-chief copy editor at the Ryerson Review of Journalism. She is a Toronto-based writer interested in people, art, internet culture and all things taboo. Sarah is also the current editor-in-chief at Her Campus Ryerson and a self-proclaimed grammar nerd.