Just how effective is hostile environment training at protecting journalists?

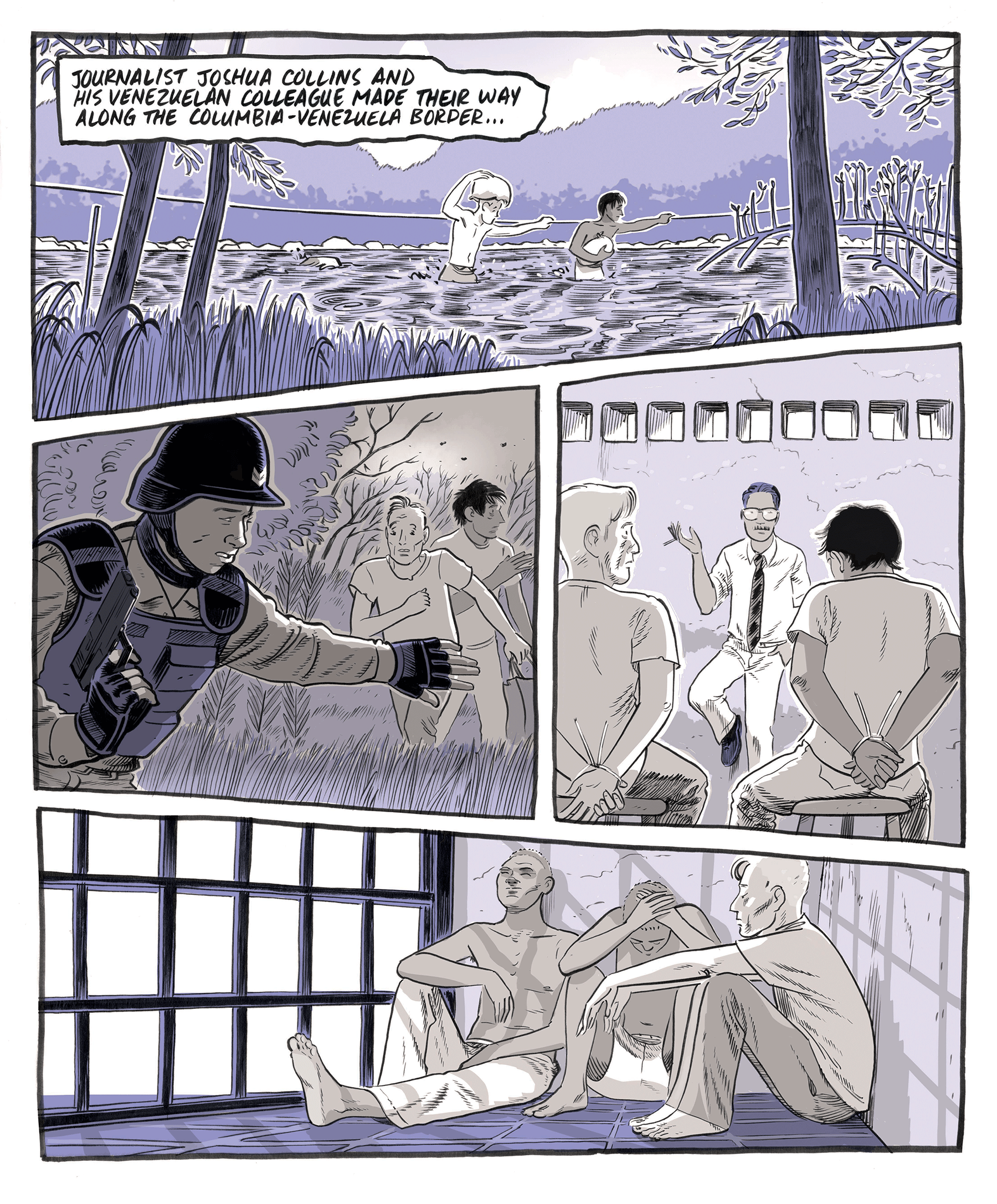

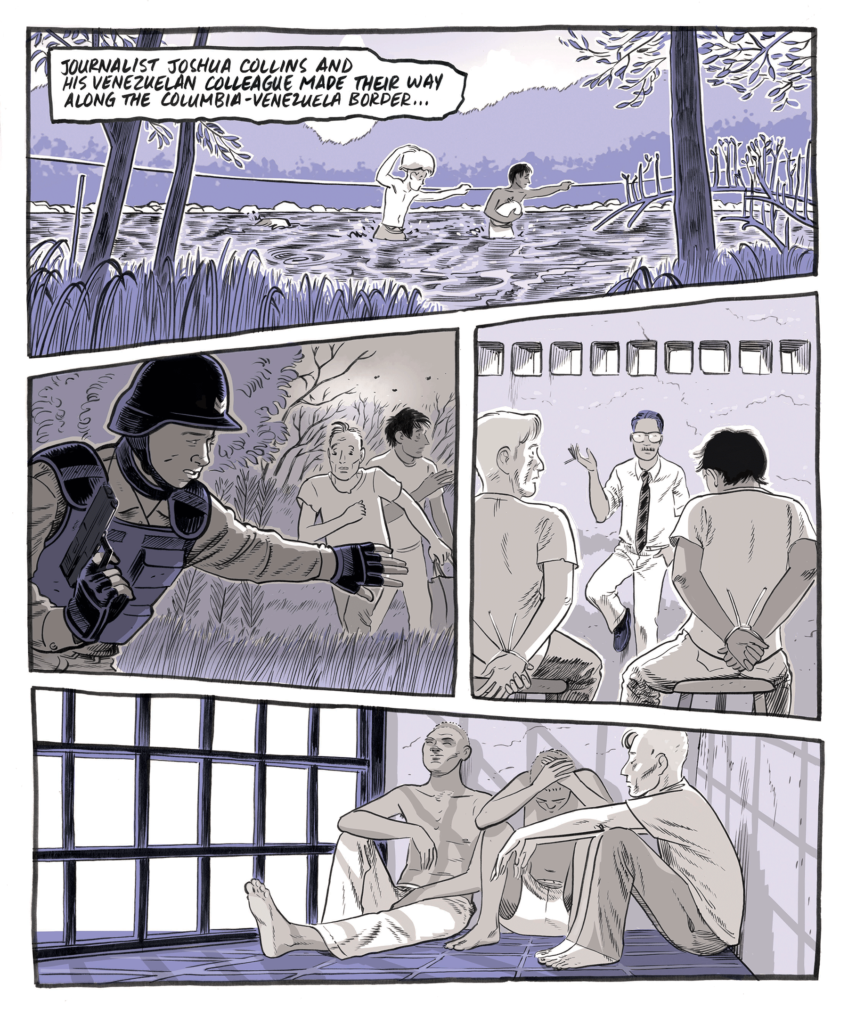

Joshua Collins is surprised when a Venezuelan national guard soldier pulls a gun on him. The freelancer thinks he’s standing in Colombia, but he’s accidentally wandered across the unmarked border into Venezuela, a country he isn’t legally allowed to enter. It’s July 2019 and he’s working on a story for Al Jazeera with a Venezuelan journalist. The guards arrest and detain both of them. A few hours later, the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service (SEBIN), Venezuela’s leading intelligence agency, shows up and questions the journalists. The agents threaten to send them to political prison in Caracas—Collins charged with espionage and terrorism, his colleague with sedition—unless they pay $10,000 (U.S.). They let the Venezuelan journalist go back to Colombia to get the money, while interrogating Collins in a concrete cell. “They were just trying to scare the crap out of me, and it worked,” he says later. “I was just trying to not have a heart attack.”

When the Venezuelan journalist gets out, he calls several editors and news organizations from Collins’s phone; three outlets get ready to run a story about a detained American journalist. Thirty-six hours later, the guards let Collins go, but they keep his camera equipment and warn him that any story he publishes may cause problems for his partner’s family.

After this close call, Collins said Al Jazeera wouldn’t hire him again if he didn’t do Hostile Environment Awareness Training (HEAT). HEAT courses teach people who work in war zones how to be safe. Typically between three and six days long, they include classroom lessons and practical scenarios covering first aid in the field, kidnap training, negotiating at checkpoints, and other high-risk situations. But each course is different because the industry isn’t standardized. And as situations like Collins’s pile up, it’s vital for journalists to be prepared, even if they aren’t going directly into war.

In the past decade, 702 professional journalists have been killed, according to an analysis from Reporters Without Borders, a non-governmental organization dedicated to protecting the freedom of the press. The report, called “World Wide Round-Up of Journalists, Killed, Detained, Held Hostage, or Missing in 2019,” found that 29 of the 49 journalists killed during the year were killed in peaceful countries and none were foreign correspondents, suggesting that reporters should be wary of more than war. The report also found that 389 journalists were (and still may be) detained. That number is 12 percent higher than the year before.

In an effort to keep these numbers low, more newsrooms are sending reporters to HEAT. In the United States, some National Public Radio reporters did a version of the training ahead of facing rowdy crowds at Trump events. Canadian journalists, including those from CBC and the Toronto Star, also do the training but few Canadian companies offer courses. More important, some reporters find the programs miss critical information. The training focuses on war zones and is usually run by military veterans; there is kidnap training, but no detention training; there isn’t psychological support or a major focus on how to cope with traumatizing events. So, journalists may leave knowing how to use a belt as a tourniquet, but not how to reduce their risk of PTSD.

Michelle Shephard is driving through the woods in a van with a small group of journalists. All of a sudden: gunfire. Armed men in balaclavas ambush the van, drag Shephard out by her ponytail and force a burlap bag over her head. The other journalists get the same treatment. After walking for some time, they lie down in the dirt. A bug crawls up Shephard’s arm and she tries to shake it off. Suddenly, a gun is digging into her head and she hears a deep voice bark, “Don’t move.” Shephard is on edge, even though she knew this was coming.

When the journalists watch the video of the ambush, the trainers point out what could get them killed in a real hostage situation. They catch one woman stumbling. “If they had to kill someone, they would have killed you,” the trainer says. Another man wearing suede combat boots learns, “Those look like military combat boots, so they might suspect you of being a spy.” The women discover that in some countries, being married but alone may lead to suspicion. They also learn not to wear diamond rings or jewelry; kidnappers will see an opportunity for higher ransom. “I would have to say for all the lessons,” says Shephard, “that one was the most sensational but maybe not the one that taught the most.” For her, the most useful lesson was the combat first aid.

Her mock kidnapping took place in 2006 in Virginia. Back then, Shephard was a national security reporter at the Star, an assignment she landed after covering the 9/11 attacks. David Walmsley, the foreign editor at the time, sent her for HEAT before she began reporting in countries like Pakistan, Somalia and Syria. As well as kidnap training, Shephard learned about first aid, how to read a compass (and how to find direction without one), negotiating at checkpoints, dealing with landmines, and deciphering where gunfire is coming from.

HEAT training has been around since at least the early 2000s. Canadian-based Tundra Group, which began offering the courses overseas in 2006, started doing them here in 2012. The company’s training facility is across 40 acres of secluded land in Staynor, Ontario. Before 2012, Canadians had to leave the country for training or wait for an international company to come to them. Sandro Contenta, feature writer for the Star and former foreign correspondent, has had both experiences. In 2012 he did HEAT in the Star’s downtown Toronto building. Ten years earlier, though, he took the course just outside of London, England, in a rural field. Then he headed to Iraq.

American airplanes bomb Iraqi soldiers on a cliff overlooking a Kurdish town right on the front lines. Contenta watches with a fixer and a Los Angeles Times reporter on a nearby slope. The ground under their feet shakes. When no more fire comes from the Iraqi side, they make their way down to the scene. All of a sudden, mortar shells start flying. The first one lands and explodes less than 100 metres away. Bombs fly overhead, so the team dives into a nearby ditch. Contenta looks over the edge and sees American Special Forces fleeing. If the military is getting out of there, he thinks, he probably should, too. His fixer leads them through a nearby field. Since it’s being farmed, it probably isn’t littered with landmines.

In situations like that one, Contenta felt that HEAT had best prepared him to handle a medical emergency. In training, he not only learned how to stop bleeding but how to construct a makeshift stretcher. Shephard found the medical training and self-care tips while in captivity, like pulling a thread from a shirt to use as dental floss, the most useful. For Collins, learning how to keep someone—or yourself—alive long enough to get medical attention was essential. His training also focused on the motives of guerilla fighters and others who’ve caused problems for journalists in the past. Although Contenta, Shephard, and Collins left training knowing how to deal with medical emergencies, which also happen outside of war zones, they missed out on vital lessons they would later learn on assignment. Contenta wants a meaningful emphasis on stress-coping mechanisms and mental health. “Even if you’re not the one who gets shot at,” he says, “you’re going to see people who have been shot or who have stepped on landmines and that’s very traumatic.”

Thomas Willard agrees. A former officer with the Norwegian Armed Forces, he’s now the head of global health, safety, and security training unit at The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) in Oslo, Norway. He designed his HEAT course with mental health professionals and other hostile environment experts. He thinks some companies delivering HEAT are cutting serious corners, notably psychological support. One of his top priorities is the trauma participants may experience or bring with them. “We need to make sure that we do not destroy people,” says Willard. The council enlists help from the California-based Headington Institute, which works with companies sending people, such as humanitarian relief workers, into war zones. “It’s not only about being in the field,” says Willard. “But it’s about how we think, how your mindset is regarding your own safety and security.”

The council didn’t always work this way. Willard revamped the program, which he thought was too focused on policy, after he joined the council in 2016. Now, his goal is for participants to turn their focus on themselves and their coping skills in stressful situations. A psychologist is available to the participants 24/7, and at the end of every day they do mental debriefs in small groups. They also get a reflection book to work in after every session. “This is a training about personal development, and your own awareness towards how you can be safe when shit hits the fan,” says Willard. The psychologist is also available after participants finish the course, with the understanding that stress may surface days, or even weeks, later.

The revamp came a few years after the NRC landed in legal trouble. In 2012, Steve Dennis was working for the council in the Dadaab refugee complex in Kenya. On June 29, he was travelling in a convoy with colleagues when a group of men started shooting at them. Several people were injured; Dennis was shot in the leg and his driver was killed. Dennis and three others were kidnapped and taken to Somalia. Four days later, they were rescued by a pro-Kenyan government Somali militia. After returning home, Dennis developed PTSD and depression. For several months, he tried to reach a settlement with the NRC, but the case ended up in court. In 2015, he won his lawsuit and was awarded $678,000; the council was found to have been grossly negligent.

“Obviously, they were all traumatized,” says Don Bosch. As the director of risk psychology and HEAT training at the Headington Institute, he works with the NRC to make sure HEAT participants are mentally prepared for threats. He describes the 2015 lawsuit as a “watershed moment for the humanitarian world.” Now, organizations are aware that the legal system can hold them responsible for not properly preparing and taking care of their employees in hostile environments. This is also a concern for Canadian newsrooms. Federally regulated corporations, including CBC, are required to follow training requirements under the labour code. CBC sends reporters to HEAT every three years.

Bosch trains people to actively cope during a scary situation, and not just deal with the aftermath of trauma. This is called high fidelity stress exposure training. “I basically start by saying, ‘Look, it’s one thing to be surprised by a real bad event out there in the field. It’s even worse to be surprised by what comes up inside of you,’” he says. Those surprises can expose people to dangers such as getting shot at a checkpoint. His training includes a questionnaire designed to pre-screen participants, a presentation on how the brain works in new circumstances and realistic stressful scenarios. “Why? Because the brain needs to get used to it,” says Bosch. Once they know how each participant reacts under stress, they can then teach them how to stay in control, which is personalized for each participant. Two common responses to stress are laughter and anger—responses that typically don’t go over well in conflict. “Okay, look, this is your physiological tendency,” says Bosch. “You can’t help it. It just is. But when you feel that coming on, bite your cheeks. Do something because laughing is going to put you in danger.’”

Dr. Anthony Feinstein was the first to publish research about the mental health of war reporters. In 1999, he was treating a frontline reporter with unusual neurological symptoms. They turned out to be stress related. “You’ve been unwell for some time, why have you not sought help earlier?” he asked her. “You don’t understand this profession,” she said. “If you reach out for this kind of assistance, essentially your career is over.” This experience inspired the associate scientist at Sunnybrook Hospital to study the mental health of war reporters, but he couldn’t find a single publication. He applied for funding from the Freedom Forum in Washington to start his research. Now a professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto, he has written two books on the subject and co-produced Under Fire: Journalists in Combat, a film that was shortlisted for an Oscar nomination. “I didn’t realize how dangerous the profession was,” he says. “When we started to tally the near-death experiences that these journalists had gone through, I found it astounding.”

Feinstein thinks the mental health landscape for journalists has changed: it’s better, and it’s worse. News organizations started taking his research seriously and he’s led seminars at The Globe and Mail, The New York Times, and CNN. “If possible, the environment has become even more dangerous for front-line journalists,” he says, “with the rise of ISIS and the fact that journalists are now regarded as high-impact hostages and high-profile hostages.” That danger and smaller budgets mean newsrooms are sending fewer reporters to war zones. But journalists still need more education about risks like depression, PTSD, and panic disorders.

Shephard and her team have been reporting for days in Guantanamo, where the army tightly censors photos. A public affairs officer looks through her camera. “You have to delete that,” he says of images showing the ocean. “Fine. Why is that a security risk?” says Shephard. The officer stares at her blankly. “If you’re going to tell me that this is a national security risk…tell me why,” she says. The two get into a heated debate before she deletes the photos. That’s when it dawns on Shephard that soldiers don’t question anything, or if they do, they don’t ask. “The military is trained to follow orders and not question authority and we’re trained, or we naturally do question authority,” She says she believes that soldiers and journalists are wired differently.

She thinks training about dealing with these situations would be helpful. But to do it properly would require a stronger mix of instructors—her trainers were all military veterans. “It would be a great course if you could devise one that would have a really good, seasoned, respected diplomat, or maybe somebody who had been in a non-government organization,” she says, suggesting Doctors Without Borders as an example. “A lot of foreign reporting is really closer to them than actually being military. We’re not armed, we’re not part of a group.”

Oscar Cosman Brøndum also believes that journalists face unique obstacles in the field. The head of training at Guardian, a Danish risk-management company that employs trainers with various backgrounds including military veterans, non-government organization workers, hostage negotiations, and reporters says, “Journalists are an interesting bunch of participants because, in their profession they sort of run in the opposite direction as everyone else.” With that in mind, the company started tailoring the training specifically for journalists. For example, Guardian teaches reporters how to stay safe without leaving crowds. The training also includes negotiating at checkpoints and surviving a hostage situation. “The examples we use in training shouldn’t be related to the military,” says Brøndum. Soldiers don’t have to do as much thinking for themselves as journalists and aid workers, so the scenarios revolve around traveling in a small group, or alone.

When Collins took his course, he was the only participant and his trainer was a military veteran. It lasted only three days, and oddly, included gun training. “I’m not sure why that was included….[I]t’s strictly prohibited for me to carry a firearm,” says Collins. “If I was caught with a gun on a job for any media company, they would never hire me again.” Plus, gun laws in Colombia are incredibly tight and Collins would have a hard time getting a license to carry one. Despite this experience, he still benefited from HEAT. But some journalists aren’t convinced.

When Martin Regg Cohn was the foreign editor at the Star from 2006 – 2008, he sent two veteran reporters to HEAT. He had done the training in London, England, during his second tour abroad in Asia, and although he had years of experience, he learned a lot. Thinking his reporters would feel the same way, he was surprised to get a different reaction. “They both vigorously opposed going,” he says. The two journalists believed they wouldn’t learn anything given their extensive experience in war zones. So, he made it clear they would not be sent abroad without doing the training, which was already mandatory. In particular, he thinks medical training is the most useful since resources are limited in the field. “If you’re in Afghanistan, in a minefield somewhere in the middle of nowhere, you can’t call the Toronto ambulance service,” he says. “So that was interesting, when you learn about how to deal with people’s guts coming out of their bodies.” Luckily, he’s never had to deal with guts coming out of any bodies. But the training is useful wherever journalists go—injuries happen in Canada, too.

Mohamed Fahmy is managing a team of reporters in Cairo, Egypt. They work in a makeshift office in a hotel room and are broadcasting stories about the military overthrowing the Muslim Brotherhood. He’s the bureau chief of Al Jazeera English and, as of December 2013, has been on the job for more than three months. That same month, the Egyptian authorities arrest Fahmy and two other journalists, Peter Greste and Baher Mohamed. They are accused of spreading false news and working with the over-thrown Muslim Brotherhood. The guards of Cairo’s Scorpion prison lock Fahmy up in a concrete maximum security cell with no windows. It’s freezing and he sleeps on the floor. Insects crawl around him. The possibility of a death sentence hangs over him for the 438 days that he’s detained. After two years of legal battles, including two trials and two convictions, Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi, president of Egypt, pardons Fahmy. He returns to Canada in October 2015.

The training he took a decade earlier didn’t cover being incarcerated or in jails. There was kidnap training, but that’s completely different. “You are still in a system,” he says. “You’re not in the hands of a militant group that is unpredictable, that can just kill you at any time.” He also learned nothing about the long-term mental health risks of being incarcerated or war reporting.

But even if journalists did receive such training, there are no guarantees and the conversation doesn’t end with HEAT. Contenta believes the newsroom culture surrounding reporters and PTSD has only recently started shifting. “I think they’re realizing the sometimes very deep impact that war zones can have on journalists,” he says. But even after HEAT training, and nine years in war zones, he’s still left with the question: how do we deal with the toll?

About the author

Grace Wells-Smith is a senior print editor at the Ryerson Review of Journalism. She is the assistant editor at The Dance Current magazine and is achieving her masters in journalism. Her features have been published by CBC and Intermission magazine. She is a former CBC investigative intern.