How the two founders of The Narwhal are employing robust investigative journalism and stunning visuals to re-energize coverage of climate change

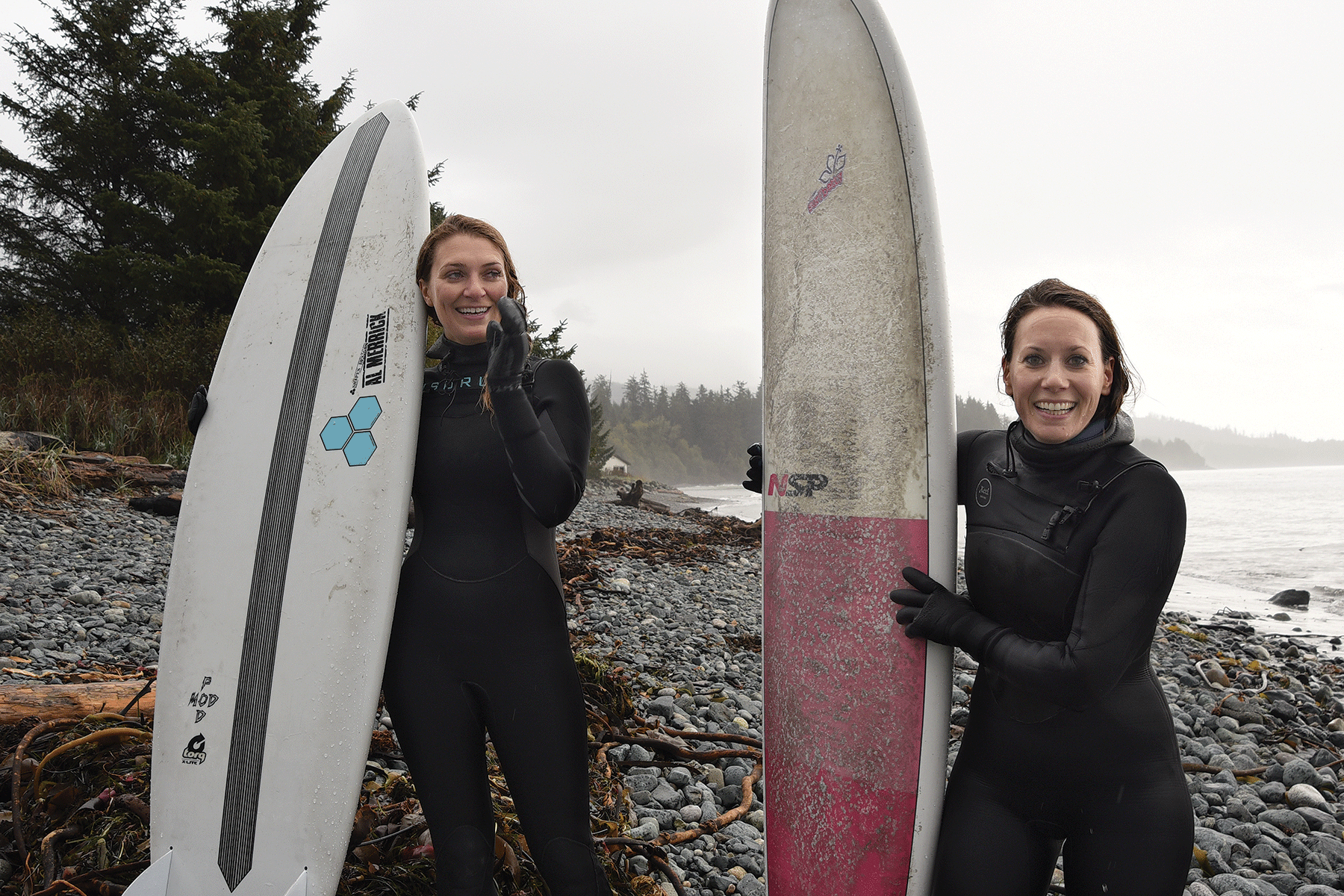

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”10″]T[/su_dropcap]he remnants of a typhoon sweep across Vancouver Island’s coastline the day The Narwhal co-founders, Emma Gilchrist and Carol Linnitt, head out for a morning surfing trip. With similar long hair and wide smiles, the two could be mistaken for sisters. The drive through Victoria’s suburban neighbourhoods quickly gives way to a windy road bordered by moss-caked rock cuts and dense forest. Mist clings to mountains in the distance. It’s a mid-October Thursday morning and instead of going to their co-working space in Victoria, Gilchrist and Linnitt are driving to Jordan River, a popular surfing spot about 70 kilometres west of Victoria. When we arrive, Gilchrist walks to the edge of the beach and looks over the water. “The way Emma surfs is so much like the way she runs The Narwhal,” says Linnitt. Gilchrist is positioning, patiently waiting for a wave, then paddling out in time. She is not out there to get pummeled in the waves. “You control very little, and it’s true in life too, you control very little. It is all about the conditions and being perceptive to the conditions and then being in the right place at the right time,” says Gilchrist.

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”10″]G[/su_dropcap]ilchrist and Linnitt believe now is the right time for an online investigative journalism magazine focused on the environment. So far they seem to be correct. Launched almost two years ago, The Narwhal has roughly 280,000 unique visitors to its site each month, including approximately 1,000 paying members, and it has attracted financial support from major international foundations devoted to environmental causes. It has also garnered multiple awards and nominations from groups such as the Canadian Online Publishing Awards, the National Magazine Awards, the Canadian Association of Journalists, and the Digital Publishing Awards.

Just how to cover the environment is something Gilchrist and Linnitt talk about a lot. “There’s no shortage of environmental stories to be written,” says Linnitt. However, they have chosen to focus on the extractive industry. “You won’t find us writing a lot about single-use plastic or something like that; where we’re much more focused is on the major power holders in society and in our democracy,” she says. “And we feel like that’s a place we can have a real impact.”

The Narwhal fills a void—covering stories on environmental and climate issues stemming from the energy industry in Canada, according to Chris Turner, author, journalist, and speaker on global energy transition. His most recent book, The Patch: The People, Pipelines and Politics of the Oilsands, discusses the impacts of oil sands in Northern Alberta. “I think [The Narwhal] really fills a need that a lot of mainstream outlets wouldn’t have the capacity or the expertise for,” he says.

In practical terms, that means an average of five stories a week, from short 1,500-word explainers to investigations upward of 3,000 words on subjects ranging from irresponsible mining practices to a close look at the people dependent on Canadian extractive industries.

Until recently, all of this was accomplished by four full-time staff members, led by Gilchrist, 35, editor-in-chief and executive director, and Linnitt, 35, managing editor. As editor-in-chief, Gilchrist checks large features and does big-picture planning for future The Narwhal stories. As executive director, she’s responsible for fundraising, hiring, public speaking, attending conferences, and developing digital strategy. Linnitt focuses on copy editing, fact-checking, communicating with freelancers, and calling sources if more comment is needed. She writes headlines and decks, and designs maps for pieces, along with posting articles on the website. Sarah Cox is the British Columbia reporter, and Sharon J. Riley the Alberta investigative reporter. Most of the content is produced by freelance reporters, photographers, and videographers, who cover mainly British Columbia and Alberta stories.

For the last two years, the publication’s staff remained the same as they steadily built an audience. But this spring, despite the current hostile media environment, The Narwhal will grow.

[su_quote]Open the website and you see striking landscapes that stretch across the screen—the idea is to tap into the reader’s feelings for the natural world through the use of beautiful images[/su_quote]

Gilchrist and Linnitt met while working for DeSmog Canada, a branch of DeSmog Blog, a global news site working to counter an “organized public relations campaign poisoning the climate change debate.” After graduating from York University with an MA in English literature, Linnitt began her career writing and doing interviews for the Canadian Expedition, a non-governmental sustainability initiative. In 2010 DeSmog Blog hired her to research a story on fracking for natural gas, then kept her on as energy reporter. In February 2013 DeSmog Canada launched and Linnitt appointed as managing editor and director of research. Interest in environmental issues was growing—the Northern Gateway pipeline was in its public hearing stages. “DeSmog Canada was growing really fast and we needed more editorial support,” recalls Linnitt.

In November 2013 Gilchrist, then the communications director at Dogwood, a non-profit environmental advocacy organization in Victoria, was recruited as deputy editor. She brought experience from her early career—in 2007 she had started the award-winning Green Guide, an environmental advice column at the Calgary Herald. At Dogwood she learned how to mobilize people to lobby the government. But there was a deeper impetus: Gilchrist had grown up in Valleyview, Alberta, knowing she had been adopted, and the search for her birth mother was, in part, what drew her to journalism. At the time, the Alberta government sealed adoption records and Gilchrist wondered why. This fueled a passion to investigate governments’ practice of securing documents.

At DeSmog, Gilchrist and Linnitt bonded over a shared love of surfing and music festivals. Soon, they turned to re-imagining how they could do environmental journalism, though neither can pinpoint when they decided to launch The Narwhal. At first, Linnitt was resistant to the change. After all, DeSmog Canada was doing well, gaining readers and recognition. The philosophy in a corporate strategy book called Playing to Win changed Linnitt’s mind. The idea was to shift to a mindset of winning rather than focusing on what could be lost. “I realized that all of my hesitations about the rebrand, even the potential changing the name, really came from a fear of losing.”

Gilchrist remembers when she thought of The Narwhal as a name for their new publication. It was just over a week before Father’s Day, 2017, and she had bought a “Canadiana” apron for her father. The apron had cliché Canadian icons on it: a Mountie, beavers, maple leaves, a moose—and a narwhal. Gilchrist texted a photo to Linnitt and asked her, “What about The Narwhal?”

“I had two immediate thoughts. I thought, oh, my gosh, that is an amazing idea and the other was it is too hip,” recalls Linnitt. She worried narwhals were a fad and she didn’t want to compete with online chatter about the beloved creature. But soon after their conversation, Gilchrist obtained the web domain for thenarwhal.ca. These “sea unicorns” don’t survive in captivity and are threatened by climate change and commercial fishing. They can dive deeper than 1,500 metres. “There were just so many overlapping metaphors with investigative journalism, in-depth investigative journalism about the natural world,” says Linnitt.

The name was approved by their board of directors, carried over from DeSmog Canada, in March 2018, just months before the May 14 launch. Linnitt’s concerns about losing members with a name change were largely unfounded. After five years operating as DeSmog Canada, they had 200 members. Eighteen months into life as The Narwhal, they had five times that number (1,000). “I think it was a smart rebrand for sure,” says Brendan Glauser, a The Narwhal reader and associate director of communications for the David Suzuki Foundation. “You create a brand around an animal that people can feel some pride around, feel some love for. You make it clear that you’re committed to protecting and restoring the natural world and that kind of vibe to that brand.”

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”10″]I[/su_dropcap]nvestigative journalism is a core part of The Narwhal’s content, but in an effort to reach a broader audience, they also employ high-quality visuals. “We really wanted the site to showcase the images—that was really huge,” says Gilchrist. “Because we don’t have advertising, we are able to design a site that is really visual and beautiful.”

Open the website and you see striking landscapes that stretch across the screen—the idea is to tap into the reader’s feelings for the natural world through the use of beautiful images, says Linnitt. “Canadians do have a strong shared value of the beauty of our natural environment, celebrating it. That brings people together; that is not divisive,” she says. Canadians earning a living from the energy sector are stereotyped as having a disdain for environmental causes, adds Gilchrist. “It’s so easy to characterize these things as really black and white, but everybody cares about water, everyone cares about the environment on some level.” Perhaps true, but they may not all be searching out The Narwhal, gorgeous photos or not. “The problem for any sort of specialty media is you usually end up preaching to the choir, right?” says Jack Knox, a columnist at Victoria’s Times Colonist and a Narwhal reader. “If you go grab ten Narwhal readers off the street…nine of them vote Green.”

Those who do find the site see environmental and energy stories divided into 10 categories, including news, investigations, photo essays, opinions, profiles, plus videos and a podcast. New stories are published about five times a week and each piece is punctuated with photos, and, at times, illustrations and maps. In the week of February 10, the stories that go up include pieces about the Wet’suwet’en opposition to the Coastal Gaslink pipeline and a feature on a proposed gold mine threat to Nova Scotia’s Atlantic salmon. The images often show readers remote locations—for example, BC’s hydroelectric project, Site C dam in the Peace River area of northeastern BC. Gilchrist says, “To appreciate the parts of the natural world that are being sacrificed, you need to see them.”

Each story lists an estimated reading time. Ben Parfitt’s investigative piece, “Inside BC Hydro’s lost battle to protect major hydro dams from fracking earthquakes,” around 3,300 words, is said to take 17 minutes. The Narwhal profile, “Iranian scientist spent her life fighting for Indigenous voices in conservation,” a 1,400-word piece by Jimmy Thomson, is described as an eight-minute read. “It helps people, I think, determine whether they want to read it right then or maybe read it later,” explains Gilchrist.

One of those long reads—29 minutes—a piece Gilchrist is particularly proud of, is 2018’s “Life After Coal,” by Alberta reporter Riley. A finalist in the labour reporting category at the 2018 Canadian Association of Journalists awards, the piece delves into the lives of six coal miners after the government phased out coal-fired electricity in Alberta. One describes how he worries about his grandchildren: “I’d like them to grow up in a world without having to put up with all this pollution and with climate change that’s causing worse storms….

I believe man has contributed to that climate change.” Riley explains, “There are all sorts of preconceived notions about how people working in various extractive industries are going to perceive the world, and having the chance to go and spend time with them and really talk about their feelings and their opinions—I think it brings a more complete picture.”

[su_quote]The apron had cliché Canadian icons on it: a Mountie, beavers, maple leaves, a moose—and a narwhal. Gilchrist texted a photo to Linnitt and asked her, “What about The Narwhal?” [/su_quote]

Since then, Gilchrist has embraced a journalistic practice called “Complicating the Narrative,” promoted by the New York-based non-profit Solutions Journalism Network. In 2018 and 2019 she attended two workshops, which she says provided “the language to understand how to report on conflict in a way that is productive instead of polarizing.” Another Riley piece, “After Oil and Gas: Meet Alberta Workers Making the Switch to Solar,” which appeared in October 2019, is a good example. A 2,900-word-long article, it focuses on three former traditional-energy-sector workers and shows how they might represent the thousands of others facing career change.

The Narwhal’s photography can be equally ambitious. In 2018 it won gold at the Canadian Online Publishing Awards for freelancer Garth Lenz’s “The Canadian Mining Boom You’ve Never Seen Before.” The 31 images include aerials of mountainous landscapes cut with mines and portraits of community members. Lenz says the piece took roughly $20,000 to put together. “It was very great for a small organization to provide the support to put me into relatively remote locations for a couple of weeks,” he says.

The Narwhal also produces a limited number of videos—last year it did 11—and two of last year’s, The Caribou Guardians and Coal Valley: The Story of B.C.’s Quiet Water Contamination Crisis, were finalists for the 2019 Digital Publishing Awards. The Narwhal also launched a podcast, Undercurrent, last year, and intends to do a second season.

Aerin Jacob, a reader and conservation scientist in Canmore, Alberta, appreciates The Narwhal’s visual approach. “I love that it’s beautiful. The website is nice to look at, the stories are easy to read because the format is really user-friendly. The photos are beautiful. It’s something that as a reader keeps you there.” The Suzuki Foundation’s Glauser praises the way in which the publication approaches its subject matter. DeSmog Canada seemed to be geared toward journalism “coming after oil and gas,” he says. “It’s not very good for bringing new people on side, changing minds.” Instead, The Narwhal is creating conversations, Glauser notes, “which I think is just a probably smarter way to go for really trying to make that kind of change.” Jacob also welcomes the variety of sources in Narwhal stories. “I like that The Narwhal tries to have underrepresented voices or have different voices tell their own stories.” But Lindsay Brown, a reader in Vancouver, mostly wants The Narwhal to keep government and businesses accountable. “I don’t need pictures and video. I want to see hard-hitting investigative journalism.” Brown says The Narwhal is one of the few media outlets scrutinizing the extractive industry in the province. It’s not just the public who praise The Narwhal for chasing environmental stories in a way that is not currently being done in mainstream media. Chris Turner says its stories are professional: “They don’t overstate the case for or against a thing. You can tell there’s due diligence in their reporting just by the final product.” Retired Mount Royal University journalism chair Ron MacDonald says, “I think mainstream journalism often underestimates its readers or listeners or viewers. One of the great things about The Narwhal is that it does not do that. It regards its readers as intelligent, concerned, committed, engaged people and it writes to them.”

There is evidence The Narwhal stories are reaching the government. According to The Narwhal’s Google Analytics, the November 20, 2019, story “‘Hidden danger’: Life for farmers living atop Alberta’s 400,000 kilometres of pipelines,” was read 118 times within the Alberta Energy Regulator, says Gilchrist. “United Nations instructs Canada to suspend Site C dam construction over Indigenous rights violations,” published on January 9, 2019, was read 167 times by the BC government, and the August 15, 2019, story “Canadian taxpayers on the hook for $61 million for road to open up mining in Arctic” was read 86 times at Environment Canada and 37 times at Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. After the story “‘Indicative of a truly corrupt system’: government investigation reveals BC Timber Sales violating old-growth logging rules,” was published on October 7, the issue was raised in the legislature on October 10. The reach of stories is reflected in social media. “When you just look at the kinds of people who comment on your stories, retweet them,” The Narwhal board member Candis Callison says, “you know, I think that there’s a broad base of support that isn’t just regional.”

Mainstream media have also taken notice, with The Walrus and the Times Colonist both republishing The Narwhal stories. “It’s kind of a symbiotic relationship. They can do deep dives into things that we can’t or don’t,” says the Times Colonist’s Knox. The pieces are usually provided at no charge as the goal is to reach as wide an audience as possible, says Gilchrist.

[su_quote cite=”Ron MacDonald “]I think mainstream journalism often underestimates its readers or listeners or viewers….[The Narwhal] regards its readers as intelligent, concerned, committed, engaged people and it writes to them [/su_quote]

That audience could increase with The Narwhal’s expanding budget. The 2019 revenue was almost $840,000, virtually double 2018’s figure, and Gilchrist and Linnitt expect this year’s number will reach $900,000. Reader support also grew, from $82,000 in 2018 to $230,000 last year, and the goal is to increase the number of sustaining members from 1,000 to 1,500 by fall. “I think there’s still a lot of untapped audience when you look at the possibility for us to expand into other areas in Canada,” says Gilchrist. Still, the majority of The Narwhal’s budget comes from grants. There were eight in 2019, including $157,200 from the Wilburforce Foundation, a Seattle-based philanthropic conservation foundation; $77,782 from the Boreal Songbird Initiative; and $59,947 from the European Climate Foundation.

Gilchrist acknowledges grant funding can come and go. “The reason that I’m not nervous about the grant side of things is because we’re building out the reader-funded side of things simultaneously. And that’s growing all the time.” And of course, its quality journalism keeps readers loyal to The Narwhal, yet with a healthy and growing revenue, the freelance rate—50 cents a word—could be higher. Don Genova, an organizer with the Canadian Freelance Guild, says a good rate for freelance writers is about $1 a word, though he describes The Narwhal’s fee as “not bad.” Gilchrist responds: “Ultimately we’re trying to balance producing as much impactful journalism as we can with the budget we can while paying people fairly.”

For now, The Narwhal plans to keep the freelance budget at $6,000 a month, but has more than doubled the staff. Four full-time positions—a senior editor, an audience engagement editor, a northwest BC reporter and a Yukon reporter—were added in early 2020. The two reporter positions are being funded through Local Journalism Initiative one-year grants, a Canadian government program to support the hiring of journalists in underserved areas. The editor position had been in the works for a few months. In November 2019, Gilchrist and Linnitt put out a call to increase membership by 150 people to hire a new editor and the campaign brought in 89 new members, boosting hiring efforts. Also, a part-time director of revenue and operations staff member started in February 2019. In addition, The Narwhal created a part-time BC reporter position for Stephanie Wood, a member of the Skwxwú7mesh Nation and The Narwhal’s first Indigenous reporter. She started February 5.

Early on, Gilchrist noted an issue with staff diversity. To help address this, she recruited two Indigenous board members: Toronto Star (now at The Globe and Mail) journalist Tanya Talaga and Candis Callison, a UBC associate professor in the graduate school of journalism, joined the board about two years ago. “When you are covering the environment, you cannot leave out Indigenous knowledge and Indigenous voices,” says Talaga. The Narwhal launched an Indigenous journalism fellowship funded by the Reader’s Digest Foundation, which provides $5,000 to fund a reporting project related to Indigenous communities and the natural world. The fellowship was awarded to Toronto-based Indigenous writer Kelly Boutsalis, who has written arts and feature stories for publications such as Chatelaine and Vice.

[su_dropcap style=”simple” size=”10″]O[/su_dropcap]n October 17, a man fixes a sign at a newly refurbished co-working space near Victoria’s Chinatown. The second floor of the former streetcar shed opens up to a skylight ceiling in a lounge with lemon yellow sofas. Linnitt points out a yoga studio down one hall and a reading nook with a fireplace in another section. The Narwhal’s two founders stop at a small glass-partitioned office where they hoped to set up a new headquarters, nearly six years after working for DeSmog Canada out of their homes. A week later, after Gilchrist, Linnitt, and Cox settle into a similar three-person space, they have The Narwhal logo affixed on the glass office wall.

Correction: This online version of the print piece published in the Spring 2020 issue of the Ryerson Review of Journalism was revised to correct inaccuracies. Emma Gilchrist was initially hired at DeSmog Canada as deputy editor in 2013 and became executive director in 2014. When DeSmog Canada launched they had no members. After five years operating as DeSmog Canada, they had 200 members and 18 months as The Narwhal, they had 1,000 members. The Narwhal recently hired a Yukon reporter not a Whitehorse reporter. Tanya Talaga was a journalist with the Toronto Star when she joined The Narwhal Board of Directors but she is now with The Globe and Mail.

The Ryerson Review of Journalism regrets the errors.

Beastly Books

Canadian publications and their pet names

Canadians’ love for nature is reflected in national symbols such as the flag and coat of arms, both bearing our emblematic maple leaf, along with the currency featuring caribou, beavers, and loons. This fondness for wildlife seems to extend to the publishing world. One of Canada’s earliest magazines, The Beaver, and more recently The Walrus, borrow a beloved creature for a name. Here are a few examples of journalism’s foray into the animal world:

The Beaver

The Beaver

Launched in 1920, it declared itself “devoted to the interests of those who serve the Hudson’s Bay Company.” Canada’s National History Society took over ownership from the HBC in 1994 but stuck with the tee-hee-inducing title until 2010, when it became the more prosaic Canada’s History.

Typical story (then): “Into the Arctic: Three Thousand Miles by Canoe Without Indian Guides.”

Typical story (now): “Riel’s Rebellion: The Dramatic Story of the Métis Resistance that Led to the Founding of Winnipeg.”

Tone: Earnestly educational.

Dogs in Canada

Dogs in Canada

Once Canada’s oldest continuously published magazine, it debuted in 1889, six years before Maclean’s. Though “devoted to dogs and their Canadians,” it was put down by its publisher, the Canadian Kennel Club, in 2011.

Atypical story: “Swiss tourists served shocking Hong Kong meal,” about how a miscommunication left a couple’s dog roasted and served for their dinner.

Typical story: “Gentle when stroked, fierce when provoked, that’s the Irish Wolfhound.”

Tone: Loyal to the end.

OWL

OWL

Now 44, kids mag OWL (for Outdoors and WildLife) has loosened up from the early days, when its idea of a fun article was how to make a jelly bean hang glider and the centrefold would feature, say, an octopus or a prairie dog.

Recent cool story: “Super School Hacks”: sprinkling baking soda on your socks to keep them from getting smelly.

Recent old-school story: “Smart like a PIG!” about how pigs are more clever than dogs.

Tone: Excitable—as many as 12 exclamation marks per page.

The Walrus

The Walrus

When The Walrus lumbered onto the scene in 2003, editor David Berlin explained the eccentric name by saying that a walrus is “able to go deep and be on the surface and be a bit curmudgeonly.”

Definitely a surface story: “Usuk Envy,” in the first issue, about the author’s impulse purchase of “a very large, very hard” walrus penis.

Quintessential story today: “The Making of Margaret Atwood.”

Tone: Aspiring Atlantic.

The Tyee

The Tyee

Launched in 2003 with a catchy tagline—“A feisty one online”—Vancouver-based The Tyee was an early web-only publication (Tyee is a Nuu-chah-nulth word for both leader and a spring salmon over 30 pounds).

First-ever crowdfunded story in Canada: Chris Wood’s 2006 “Rough Weather Ahead,” about faulty Fraser River dikes.

Story hinting at its political slant: “Put the Billionaires on a Rocket to Mars.”

Tone: Smart Left Coast

About the author

Karen Longwell quit her full-time journalism job in community news in 2018 to pursue a master of journalism. She is the visual editor at the Ryerson Review of Journalism. Her stories have appeared in the Toronto Star, National Post and in community newspapers across the country. Recently, she has been on the cannabis beat and is passionate about climate change, social justice and international issues. She works hard but is easily distracted by online cat videos and chocolate.