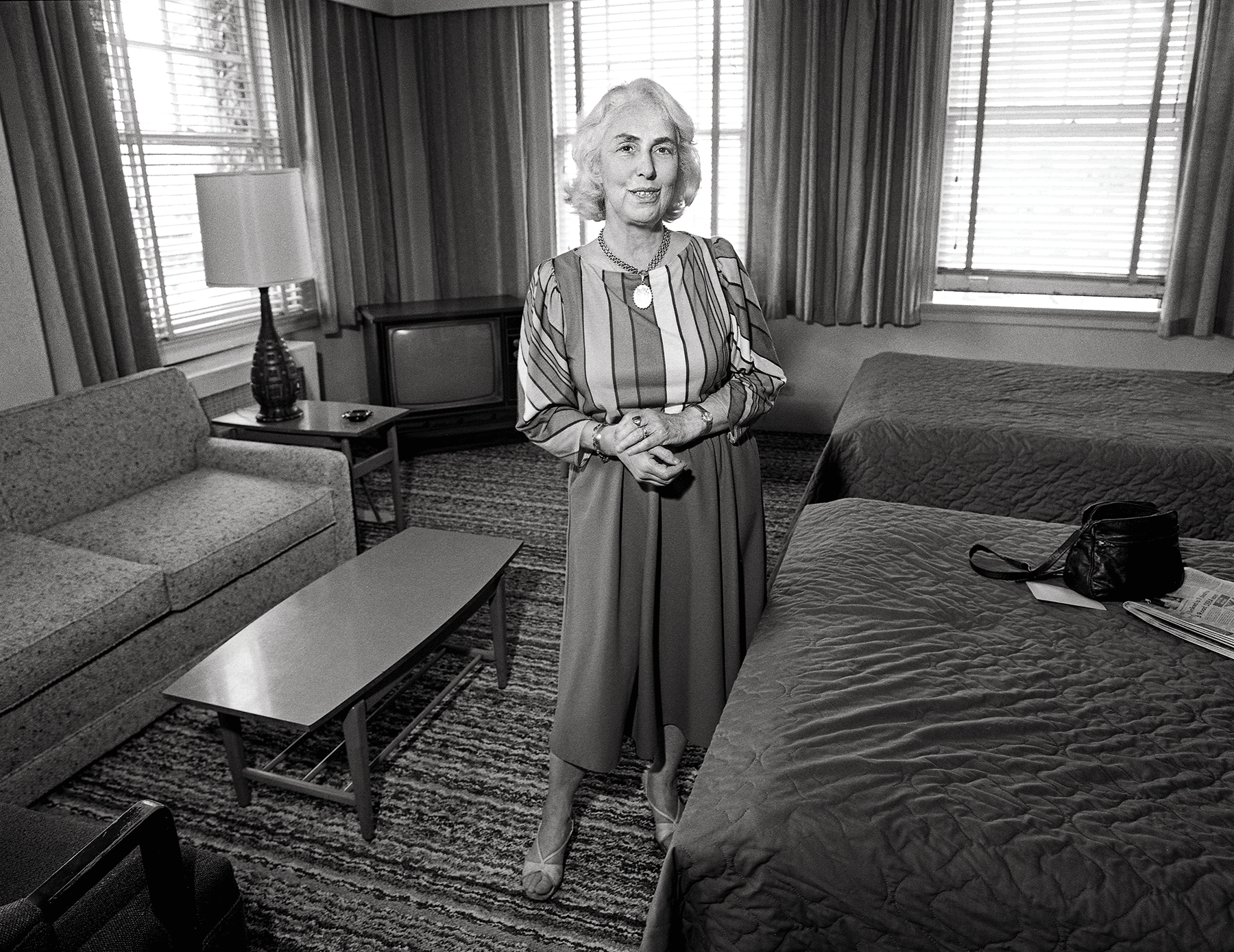

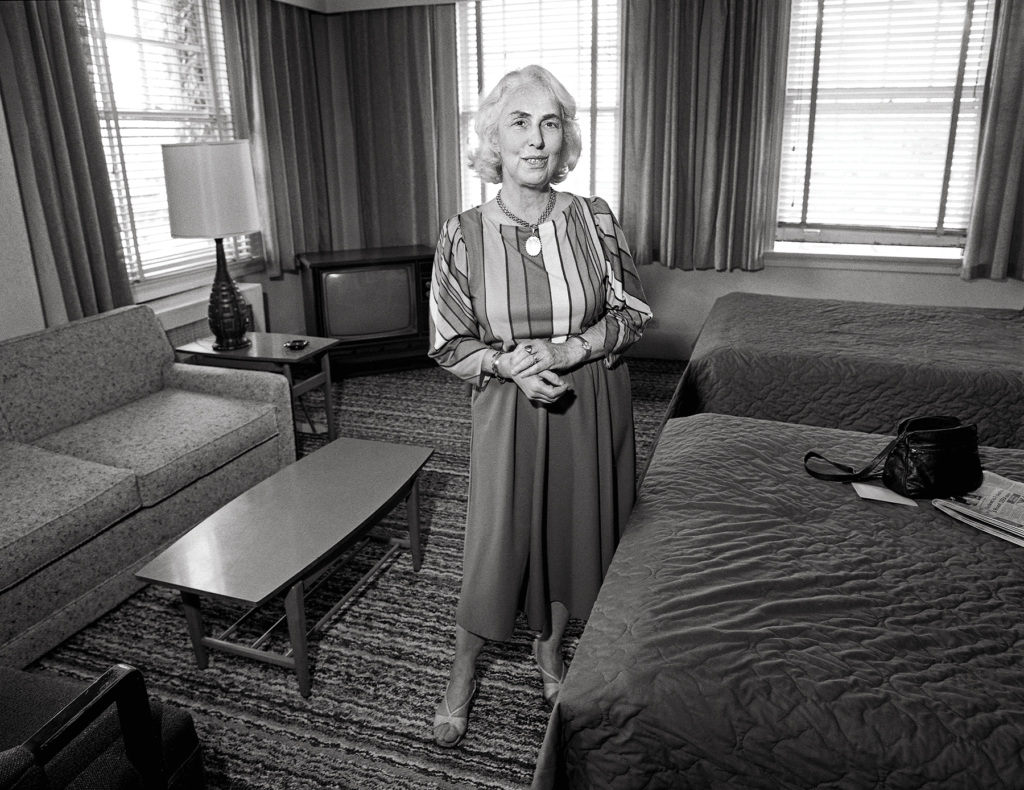

The vivacious writer Edith Iglauer explained Canada to Americans and vice versa

We waited in the living room in a sort of funereal silence. Ten minutes later the doorbell rang and everyone sat up very straight. I was conscious of the clicking noise my heels made as I ran to the front door in our small hallway. I don’t know what I expected, but there Pierre Trudeau was, there he really was, standing outside, with a big smile. As always when I saw him, I was startled by the brilliant blue of his eyes, accentuated by a cool blue shirt. The customary red rosebud in the lapel of his immaculate blue business suit matched his red tie.

The broken elevator, the RCMP watching the cook, and the soggy raspberries were some of the highlights Edith Iglauer recalled in “The Prime Minister Accepts,” her 2007 memoir of meeting the Canadian leader for Geist magazine. A dinner long remembered by Iglauer, with its spectacular menu of carved roses of beets and turnips, potato balls, finely sliced lamb, tomato aspic, and avocado salad (that presented an opportunity to show off the family’s silver dinnerware), great conversation, and a surprise guest, Barbra Streisand. The dinner, in November 1969 in New York, occurred months after the New Yorker published Iglauer’s profile of the newly elected fifteenth prime minister of Canada, “Prime Minister/Premier Ministre.”

Trudeau had been a difficult interviewee, evasive on purpose, both physically and in his answers, admitted Iglauer. “I had suggested that on the trip I would just observe but not try to interview him if he would give me a one-on-one session in Ottawa when the tour was over. The trade-off appealed to him. For the eight days we were travelling, we had a pleasantly informal, joking relationship,” wrote Iglauer. The piece, published in the July 5, 1969 issue of the New Yorker, was one of Iglauer’s early major encounters with Canada, a place she came to love and call home.

Born and raised in Cleveland, Iglauer studied at the Columbia University School of Journalism in New York. Her father, a department store executive, owned a cabin in the country thirty miles outside Cleveland. “She would go to the countryside every weekend to a little cabin in the woods,” says Iglauer’s son, Richard Hamburger, a theatre director based in New York. The time with her father was important to Iglauer, and they would often go horseback riding and walking. “She really actually liked being in the world of men,” he says. She knew from the get-go that writing and finding stories was her life’s work, according to an obituary her longtime friend and editor at Geist, Mary Schendlinger, wrote in The Tyee. “I found a journal that she had written when she was 16 years old,” says Hamburger. “She always wrote—that’s how she thought.”

“You should always listen to the small, still voice at the back of your mind” was Iglauer’s motto in life and in writing, according to Howard White, her publisher and stepson. She was a vivacious, hardworking woman. Her insatiable curiosity for life and high energy sustained her through 101 years, before she succumbed to pneumonia on February 13, 2019 at a hospital in Sechelt, B.C., near Vancouver. She handled controversial, challenging topics that focused on New York life and Canadian culture, first for the New Yorker and then for Geist, as well as in her several books. Iglauer’s adventurous spirit and affinity for nature predetermined her later infatuation with the Canadian landscape.

Before Iglauer moved to Canada, in 1974, she had been a professional journalist and author for 55 years. Iglauer began her career by joining a collective of women journalists who met each week with Eleanor Roosevelt to receive White House briefings in the early days of World War II. “Mrs. Roosevelt by then was a heroine and an inspiration to women everywhere, and was especially well-known in Europe. Bringing her press conferences to the attention of my superiors, and then covering those conferences was and is a high point in my life,” wrote Iglauer in her resume. She then served as a war correspondent in Yugoslavia for the Cleveland News in 1945, along with her husband and fellow writer Philip Hamburger, who was on an assignment for the New Yorker. While she was reporting for the News, according to Jay Hamburger, Iglauer’s other son, who is also a theatre director and the co-founder of Theatre in the Raw in Vancouver, she took danger in stride. “She was shot at,” says Jay. “Her car was in front of my father’s—but none of this deterred her.”

Iglauer married Hamburger on December 24, 1942, after they met in the Columbia School of Journalism. After the war, Iglauer wrote a series of features for Harper’s Magazine, from 1946 to 1952, on the design and construction of the headquarters of the newly formed United Nations. She then joined the staff of the New Yorker in 1961. “This was where she made her greatest mark,” says White.

The New Yorker Years

In her 1979 book, Inuit Journey, Iglauer wrote:

The trail now took us down the center of the river, winding in and out among massive icy boulders. We moved along so rapidly that we soon closed ranks with the other teams, and were travelling, five sleds together, in a long line. The only sounds were the scraping of the sled runners on the ice and the barking of the dogs. The night light was a beautiful deep blue. When I had begun to think we were going on forever, we turned a bend, and I could see the outlines of a large log building ahead, with smoke coming from a pipe on top. We had arrived at the George River community hall.

The passage is from the book but was originally written for the New Yorker in a 1962 story, “Mr. Snowden and the people.” The New Yorker stories depicted the formation in Ungava Bay, Quebec of the first Inuit-owned and run co-operatives to produce and promote their own artworks. In the book version titled Inuit Journey, Iglauer wrote an introduction and epilogue appraising the situation anew.

Although she wrote about other topics that centered on issues in New York City, Canada became Iglauer’s beat in the New Yorker. There was no competition for it, which suited her fine. Her son Richard says that her love for the outdoors and adventure motivated her interest in Canada and Inuit art. The origin of her fascination with Canada, in terms of writing about the country and its people, dates to her choice to write about Inuit sculpture. Writer and designer John Houston had put together a collection of Indigenous work from the North, and she was assigned to report on the exhibition. In addition to viewing the sculptures, she extensively researched the topic, and her fascination for Canada grew. The Globe and Mail reporter Tom Hawthorn wrote, “She wrote often of the Canadian North and expressed a sympathetic yet unromanticized view of the hardships faced by Indigenous inhabitants whose centuries long survival in a pitiless landscape had become perilous with the arrival of interlopers.”

Iglauer herself made the arduous journey of traveling the length of a 325-mile road above the Arctic Circle, as it was being built, a journey through ice and snow, from Yellowknife to Great Bear Lake. She later described her journey in her 1975 book, Denison’s Ice Road. “Which is pretty crazy stuff when you think about it, because the ice can melt and trucks can fall through,” says Jay. She recounted many adventures in the book and also suffered from frostbite. “That was serious,” says Jay, “because as time went on, we had to be very careful of her circulation.”

Iglauer being tasked with physically difficult writing assignments set her apart from most journalists. “Edith was very outspoken about the difficulty of being a female journalist throughout her entire career…and resisted being assigned to ‘women topics’ of cooking and homemaking,” says White. “She preferred to go out and beyond, like to a war zone or to the Arctic.” Due to gender discrimination at the New Yorker, she chose Canadian subject matter because no men were interested in pursuing it. They preferred more high-profile territory like New York and Washington. Before she left the New Yorker, Iglauer wrote one of the first science-based exposés of air pollution in New York in the 1960s, which helped change the clean-air law in the city. She successfully pitched ideas to her editor, William Shawn, according to a piece by Mona Lee in Senior Living Magazine. She questioned why raspberries were available in winter and why the New York air smelled, and also wrote about the years-long process by which the foundations for the World Trade Center were laid in Manhattan. She wrote a series of profiles of the artist Bill Reid, the writer Hubert Evans, Iglauer’s friend and neighbour, and most notably, the architect Arthur Erickson, “who has performed the sizable feat of adorning the North American landscape with some of its most admired structures while remaining almost unknown in the United States.” Iglauer always took the high road in her writing. Even though she made a life for herself in Canada, she thought her writing conveyed the truth about the United States to Canada and vice versa, according to Ian Austen of The New York Times. “‘The still small voice of truth,’ Iglauer said, ‘is what I hear when I am writing,’” writes Austen. It was one of the reasons she was trusted by the people she wrote about, according to White, and why she got access to these people.

The Sunshine Coast

In her 1988 book, Fishing with John, Iglauer wrote:

Nothing John has said about his boat prepared me for the first sight of her. She looked so tiny—scarcely bigger than a large rowboat. Where was this grand ship I imagined? Was it for the sake of this shabby little vessel that John hovered around radios when he came to Vancouver, listening to every weather report, dashing for the ferry to get home and make sure his boat was tied up securely, at the hint of an approaching storm?

Iglauer divorced Hamburger in 1966. In 1973, she was sent on an assignment from the New Yorker to report on British Columbia’s salmon fishery in Vancouver, and met John Daly, a salmon fisherman. Her initial intention was to remain for a short stay, but she ended up staying in Garden Bay on the Sunshine Coast of British Columbia for the rest of her life. After a mutual friend suggested Daly and Iglauer meet and do an interview, the two fell in love, married in 1974, and moved aboard his 41-foot salmon trawler, the MoreKelp, which led to her writing a memoir, Fishing with John. Daly died of a heart attack in 1978 in Manitoba at a trapper’s festival, while they were dancing. “He died practically in her arms,” says Jay Hamburger. The book depicts Iglauer’s time spent on Daly’s salmon trawler and her growing love for him and this life. The memoir was listed for the Governor General’s Award for nonfiction and adapted into a television movie, Navigating the Heart, starring Jaclyn Smith and Tim Matheson.

When White, a publisher, met Iglauer in 1973, the phrase “very exotic” came to mind, “turning up in this small village, which is populated in these days mostly by commercial fishermen and loggers.” White continues, “She had the manners and dress of a well-educated and established professional journalist from the Eastern seaboard.” White helped Iglauer write Fishing with John through her grieving state, which she managed to complete in 1988, 10 years after Daly died.

For a memoir, Fishing with John is surprisingly light on personal details. Not that White didn’t try to persuade Iglauer to probe her intimate thoughts. He says, “I wanted her to put a lot more of herself into the book because, you know, after all, she did marry this man. But in the book all she writes about is fish. And then she sort of drops in, about three quarters of the way through, ‘Oh, yes. By the way, we got married.’”

“‘No,’ I said, ‘you can’t just drop it in like that. How about telling us your first kiss or something?’”

“She didn’t like the personal, and she didn’t like inserting herself into the story.”

White says Iglauer had multiple offers from larger publishers, but out of friendship and loyalty she stayed with his publishing house, Harbour Publishing.

The Geist Years

In December 1996, while Iglauer and her companion Frank White, Howard’s father, were travelling separately in the United States, they agreed to meet at the Sylvia Hotel in Vancouver, and then drive back to the Sunshine Coast, writes Schendlinger in The Tyee. Everything went as planned until a massive snowstorm swooped in. Iglauer’s first published work for Geist, “Snowed in at the Sylvia,” published in 1997, was the result. Fan letters arrived at the Geist offices.

A year later, Iglauer published “My Lovely Bathtub,” about a gift she had received from Frank White. More fan letters came in. Readers loved her work. In all, Iglauer wrote 15 dispatches for Geist that were “short, smooth, accessible reads,” Schendlinger says. Iglauer had a clear, uncluttered, and well-researched writing style. “She was very bright and wanted to know everything about everybody.” She truly cared when she asked, “How are you?” and was always on the alert for new material.

Jay Hamburger, now 72, says of his mother, “Edith was truly in the later years, and has always been, a tremendously wonderful mother and extremely supportive of whatever Richard and I wanted to do. We were lucky that way.” Richard, 69, says his mother had great friendships and was beloved while living in New York, but it was refreshing for her to get out of the city and be a part of a community that was smaller. “She had the most wonderful sense of humour, was insatiably curious and had a smile that could light up the room,” says Richard. “She was not prejudiced, enclosed.”

White says, finally, his father and Iglauer travelled a lot in later years.

Edith Iglauer’s Most Notable Works

A spotlight on the writer’s Canadian writings and musings

THE FOLLOWING are just a few of Edith Iglauer’s most notable works on Canada, its people, and its landscape:

• “Prime Minister/Premier Ministre” (1969, New Yorker): A profile piece written about the then newly elected 15th Prime Minister of Canada, Pierre Trudeau.

• “Seven Stones” (1979, New Yorker): A profile piece written about Canadian architect Arthur Erickson.

• Inuit Journey (1979): A book describing the formation of the first Inuit-owned and run cooperatives to produce and promote their own artworks in Ungava Bay, Quebec.

• Denison’s Ice Road (1975): A book detailing her arduous journey from Yellowknife to Great Bear Lake, through ice and snow, traversing the length of a 325-mile road above the Arctic Circle, as it was being built.

• Fishing with John (1988): A book depicting Iglauer’s time spent with her second husband, John Daly, on his salmon trawler, and her growing love for him and this life.

• “Snowed in at Sylvia” (1997, Geist): Her first piece published in Geist describing her experience in Sylvia Hotel during a snowstorm and her meeting with her third husband Frank White.

• “The Prime Minister Accepts” (2007, Geist): A piece describing a dinner in Iglauer’s home in November 1969 in New York, with Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and Barbra Streisand.

• “The Ambient Air” (1968, New Yorker): Science based exposé of air pollution in New York in the 1960s, which changed the clean-air law in the city.

About the author

Sabina Seyidova is the social media editor at the Ryerson Review of Journalism. She is completing her master of journalism degree. She interned for York Region, a branch of Star Metroland Media and with CBC’s London bureau. She speaks three languages, enjoys reading, photography and is interested in the arts, culture, politics and international affairs.