In her new graphic novel, Rolling Blackouts: Dispatches from Turkey, Syria, and Iraq, Sarah Glidden travels across the Middle East to answer big questions about journalism. What is journalism? Is it ethical? Can a journalist’s work create substantial change? Rolling Blackouts tells the story of Glidden’s quest to study how news is produced, perceived, and consumed.

[su_frame]

[/su_frame]

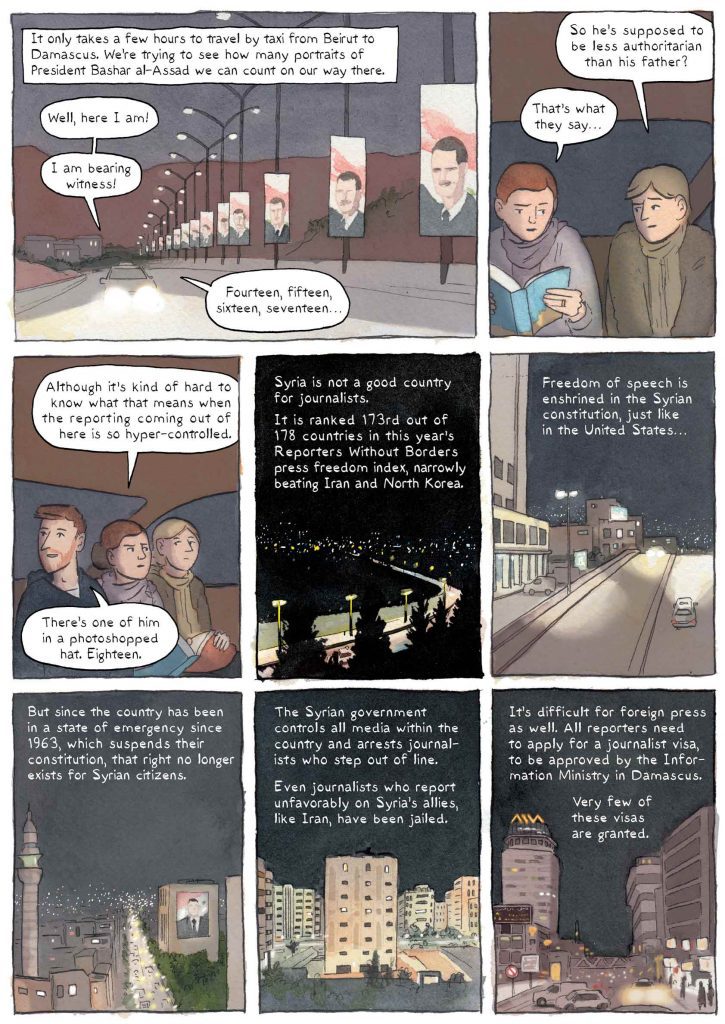

After raising the money on Kickstarter, she set off in 2010 with two journalists, Sarah Stuteville and Alex Stonehill, to personally witness their coverage of the Iraqi refugee crisis, with an ex-marine, Dan O’Brien, joining them as well. Stuteville and Stonehill are the founders of the Seattle Globalist, a website that chronicles human rights stories with accessible reporting. O’Brien, an old friend of Stuteville, joined the journalists on their trip for two purposes: first, to complete an assignment for school; second, so that the Globalist can examine how his views of the region have changed in the several years since his time there in combat. Throughout the trip, Glidden took extensive notes, photographs, recordings, and sketches of the journalists doing their work in order to recreate her experiences as accurately as possible.

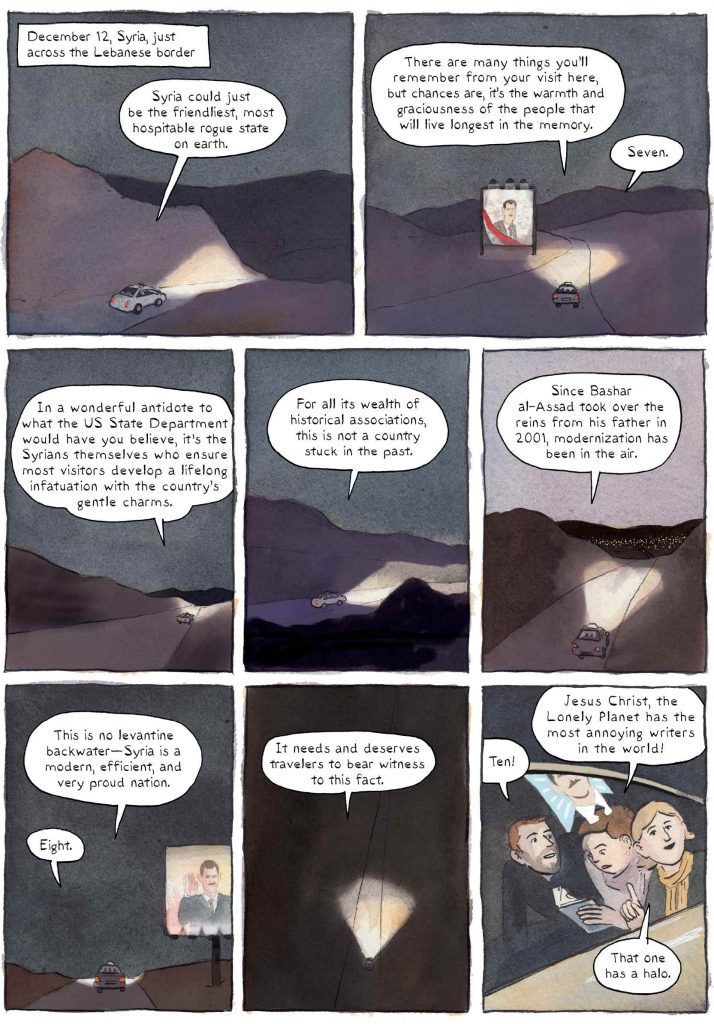

The book is truly a work of art. It consists of over 300 pages of watercolour panels, hand-painted entirely by Glidden. The book sways between deep colours in the markets of Damascus to muted greys and beiges in the Iraqi desert. Glidden has an incredible eye for details like the intersecting fibres making up a woman’s hijab, the books decorating a home, and the illuminated windows dotting the skyline as Glidden gazes from her balcony over the city of Sulaymaniyah in northern Iraq.

“It’s about making that connection, giving readers a background, showing a scene instead of describing it. These are places where people live. I want to show the familiarity of those places, the sameness of it all.”

[su_pullquote]Video: Glidden shows the work put into a single panel of her over 300 page, hand-painted graphic novel.[/su_pullquote]

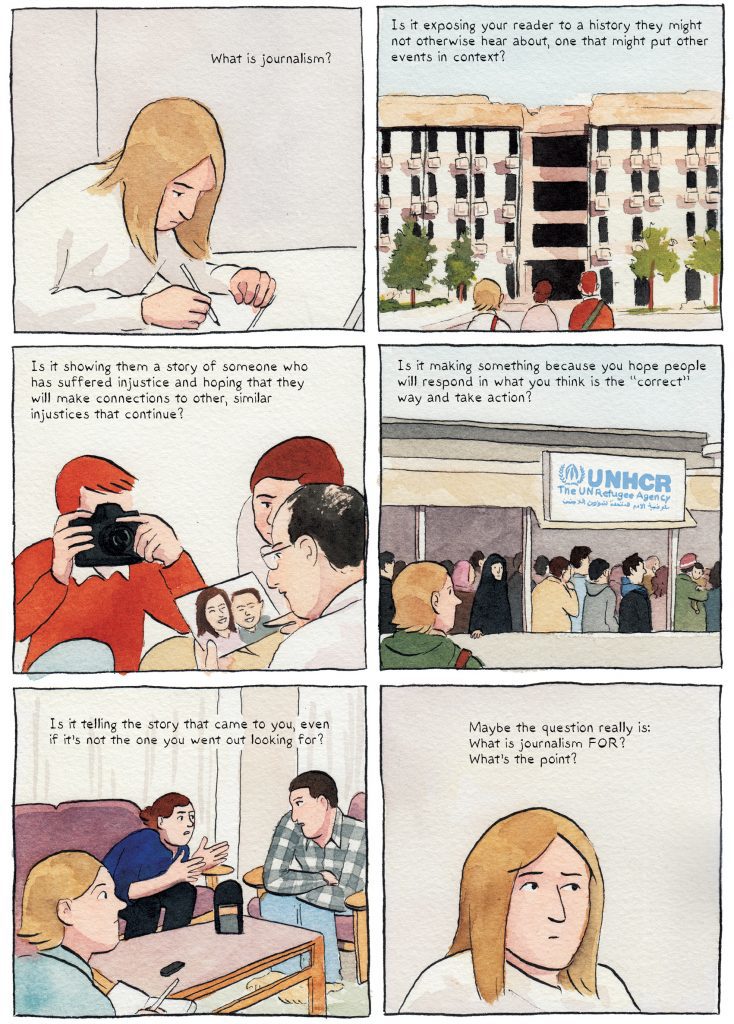

Glidden uses the journey’s events as a case study to toy with journalism’s big questions—a process that serves as a thematic thread running through the novel.

The story follows the four characters as they meet with people affected by the Iraqi refugee crisis. The people they interview include a man who was named in the 9/11 Commission papers, the founders of a school charity, photojournalists, museum guards, United Nations employees, refugees, and many others.

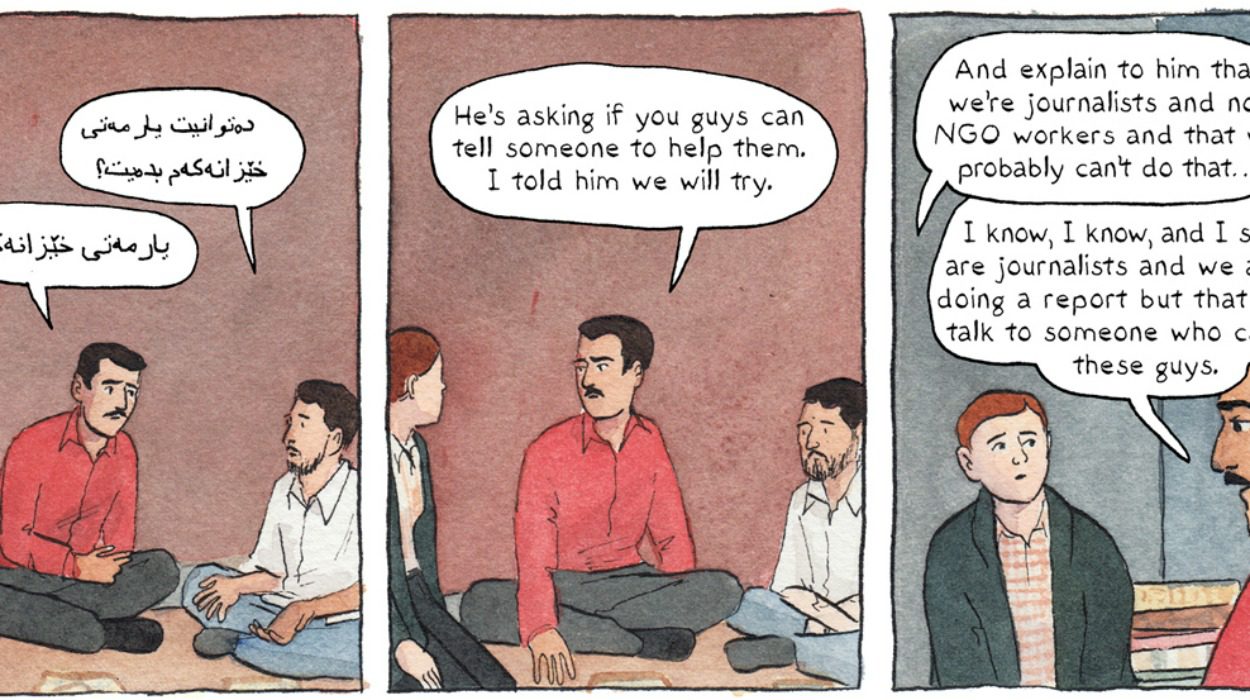

When the crew visits a camp for internally displaced people, a Kurdish father tells them that the worst part of living in the camp is the harsh cold. He begs the reporters to buy him a heater, or to help him in some other way.

Following the interaction, Glidden and her crew discuss journalistic distance, whether to make promises to sources, and the ethics of getting involved in someone’s life while telling their story.

“What is journalistic distance?” Glidden asks on the following page. “How much does it even matter?”

Glidden says that the conversation with the Kurdish man put a lot in perspective for her. “I live a life of privilege and I recognize that, especially after seeing the situations these people were in,” she explains. “It’s a very human urge to want to help, and it’s truly a waste that we can’t.”

Eager to tell the stories she found, Glidden returned home after spending two months in the Middle East. Cartoon Movement published her first piece of comic journalism in 2011—a short story about Iraqi refugees in limbo in Damascus.

“I was pushed along by the fantasy that I was going to make a difference through my work,” she writes in Rolling Blackouts. “But, of course, it was just one comic, read by a few hundred people.”

Six years later, the full-length graphic novel was published. Glidden believes that the illustration-based medium has an important asset: it can create scenes with a level of detail that words cannot achieve.

“My aim is to get people to connect to the characters and settings, and I do think comic journalism can do that,” she says. “It’s about making that connection, giving readers a background, showing a scene instead of describing it. These are places where people live. I want to show the familiarity of those places, the sameness of it all.”

Glidden says that, of the lessons she learned during her trip, one of the most important was what attitude a journalist needs to survive the reporting process: “You think, ‘I’m going to bring light to things,’ but it’s more complicated than that. You think you’re going to make a difference, and sometimes that does happen, but that can’t be the reason you’re doing it.”

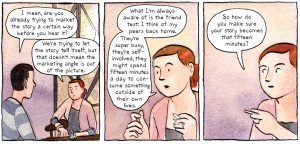

Glidden and the rest of the crew spend much of their time discussing the contemporary journalism climate. Stuteville attributes what she calls the “decline in journalism” to the internet, modern economic models, audience elitism, cable news, and highly politicized publications. “I feel like that’s the industry, not the profession,” Stuteville explains in one scene. “It’s hard for people to make that distinction, but it’s important.”

Like Stuteville, Glidden also cites funding and economic models as major problems with journalism today. “It’s a capitalist system that keeps journalism going,” she explains. “It’s not state-funded.” Her comments ironically echo the portion of the book that takes place in Syria. There, the group is assigned a “minder”: a man who follows them to their interviews, ensuring that they are not criticizing the Syrian government.

[su_pullquote]Slideshow: Excerpts from Rolling Blackouts. Click to enlarge and continue slideshow.[/su_pullquote]

She also says that, while sources may feel apprehensive, uncomfortable questions still need to be asked. “Somebody needs to go and be uncomfortable so people can understand these complex situations. When you’re doing journalism, you don’t see yourself as a hero.” She adds, “I’m sometimes concerned with how ‘white’ journalism is. The more people who come into journalism from other backgrounds and contexts, the better. It brings more to the table.”

This idea links to one of the most prevalent questions discussed by the four-member crew in Rolling Blackouts. What is Iraq’s perception of Americans, and vice versa, after the American invasion of Iraq in 2003? Their ex-marine friend, Dan O’Brien, joins them to help answer this question. He is assisting Stuteville with her piece on his return to the region as a veteran, and he is looking to get a wider perspective of the war since he fought in it several years prior.

They receive myriad responses from the people they interview, including O’Brien’s responses to their interviews with him, and Stuteville reinforces Glidden’s point that a good journalist doesn’t come into an interview hoping for a specific answer. As Stuteville talks to O’Brien, she becomes increasingly frustrated with what she believes to be dishonest answers. He continues to repeat the stance that the region’s American soldiers were well-intentioned and that, while their work may have created some negative consequences, they ultimately intended for the best.

Stuteville tries to encourage O’Brien to think critically about the role he and other soldiers played. She says that his perspective probably isn’t shared by people who became refugees because of the invasion. She then proceeds to teach one of the novel’s most important lessons:

“From a journalist’s perspective, we have to acknowledge what we don’t know.”

Glidden’s answers to journalism’s big questions are juxtaposed with an implication that the reader should figure the answers out on their own. Her ability to insert journalistic dilemmas into the context of war, refugee camps, and state censorship makes finding the answers seem urgent. How can reporters create a better world? Do journalists have any responsibility to save lives? How does a writer remove their own politics and emotions when reporting on sensitive stories?

It’s easy to get distracted from these questions when reading through Rolling Blackouts as one begins to become invested in the lives of the characters. Glidden’s group grapples with this problem as well. Not only do they worry about the man asking for a heater, but they also encounter refugees who become hostile or emotional in interviews while discussing how disadvantaged they have become as a result of war and dictatorial rule. Following one particular conversation, Glidden finds herself asking how to keep herself composed, fighting the urge to break into tears. Stuteville tells her, “it still catches up with me sometimes, but I always tell myself ‘I’ll process it later,’ because it’s not about me, you know?”

Six years have passed since that emotional interview and Glidden’s time in the Middle East, and the questions she went there to answer are still pressing. Her novel’s narrative is structured in a way that allows readers to get completely lost in its beautiful imagery, its emotional turns, and its compassion for the refugees, before she abruptly pulls you back into the important questions. Rolling Blackouts finds its power as a novel not only by raising these important questions, but also by urging the reader think critically about the future of journalism.

The book’s central theme is an in-depth exploration of what journalism is. At the outset of the novel, Glidden asks readers, “what is journalism?” Despite returning to this question in the last few pages, she provides no concrete answers, instead leaving it to readers to decide for themselves what the industry is and what its future holds.

“We’re in a time of change and growing pains,” Glidden says, laughing. “It’s easy to be pessimistic and say ‘journalism is dying,’ but I prefer to be optimistic.”

Extremely well written article. And I applaud her fresh approach and medium to a difficult topic.