Video: Maria Iqbal and Sherry Li

One woman’s brown eyes peer out and a small indent appears in the black fabric where her nose is. The other’s eyes aren’t seen, but a pink head covering contrasts with the blackness of her veil. There are more women among the crowd behind them, out of focus. No names appear in the caption. In fact, the niqab is the only hint that the two people are women.

This image appeared in numerous Canadian newspapers after Quebec passed Bill 62, which prohibits individuals from giving or receiving public services with their face covered. It was taken in 2014 by a photographer named Boris Roessler at a public gathering in Germany. The Toronto Star and Hamilton Spectator featured the photograph, but neither identified the women in the photo, or noted where it was taken. While photos taken at public gatherings frequently don’t identify individuals within them—like those of the Charlottesville protests, or even the recent college strike in Ontario, for example—they do generally note the context in which the photos were taken.

“Women in niqab in Quebec were being represented by generic stock photos of women in niqab,” says Asmaa Malik, an assistant professor at Ryerson University’s School of Journalism, referring to Canadian news coverage of the bill. “I found that very troubling because we don’t get a clear idea of who the bill affects when you use that kind of imagery, and these women become stand-ins for other women and there’s a sense that we can’t actually access or talk to women who are affected by the niqab ban.”

Malik, the graduate program director for the School of Journalism, started a research project based on the images used in the press in the coverage of Bill 62. “When you’re looking at the captions, which write around the fact that these images are from somewhere else, or don’t identify women in the photo, I think that you’re continuing to mystify and in a way, really ‘other’ these women,” Malik says. “There’s a lot of recycling and a lot of misrepresentation as a result.” A Google Image search shows that Roessler’s photo has been used in articles about niqab bans in other countries, too, including Denmark.

“The way in which Muslim women are constructed is without any national or local context, it’s the threat of Muslim women writ large, so the images can be interchangeable,” adds Itrath Syed, a PhD student at the School of Communication at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia. Syed’s research focuses on the media’s coverage of issues related to Islam, particularly periods when Muslims are at the centre of crises in the media.

“I was perplexed by how few Muslim women were actually engaged as analysts,” she says about the coverage of Bill 62. “There were some interviews on the street with Muslim women who wear niqab, or face veils, but when it came to analyzing the policy, or analyzing the larger impact, that was a lot of people outside of the community talking about Muslims.”

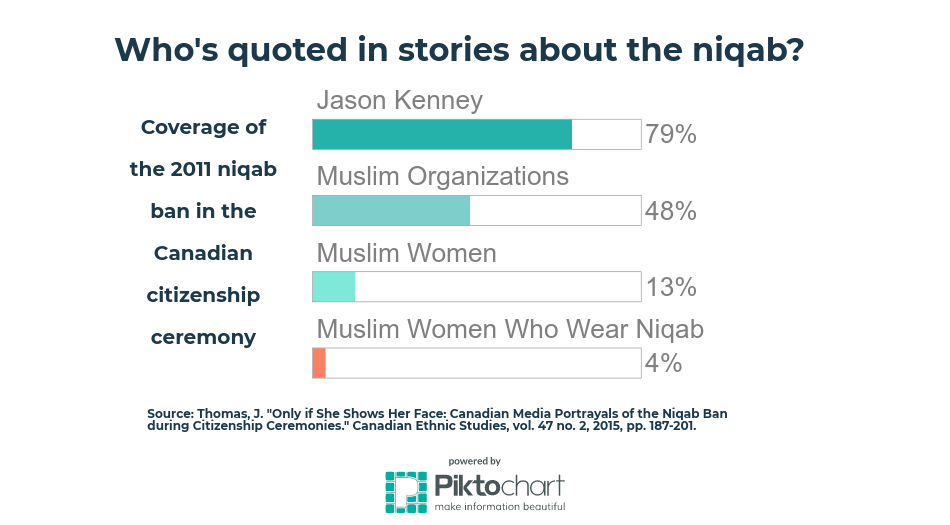

Syed’s concerns aren’t new. A 2015 article in Canadian Ethnic Studies found Canadian media articles prioritized voices from the government over those of Muslim women following the announcement about the niqab ban during the citizenship ceremony. “I don’t think the media should be harassing people on the street and saying, ‘Why do you wear this? How is this bill going to affect you?’ But I think there are ways to contact the community to meet with women who are willing and who would want to talk to the media to contextualize their choice,” Syed adds.

A Muslim woman and a recent studio arts grad from Guelph University created a photography project after moving to Canada from Egypt and noticing the absence of diverse images of Muslim women in the media. Sondoce Wasfy started Bright Muslim Women as a school project and a way to demystify Muslim women to the Canadian public.

The social media project features photos of Muslim women, many of them smiling, with captions like, “I am a Muslim Woman, I work in the biggest governmental pharmaceutical quality check laboratory in Egypt” and “Look at me! I am a Female. Muslim. Engineer.”

“I wanted to show the real Muslim women that I know,” she says, adding that she tries to take shots that “empower” their image. “I usually take lower shots where they’re more magnificent than they normally look. It’s not like a face-to-face perspective. I wanted to do that because I wanted to make it clear to people who don’t know about us that most of us, we’re not oppressed. We live a normal life.”

Though Malik says she understands the pressures the journalism industry faces in terms of resources and funding, she emphasizes that news organizations should ensure images are “as accurate as the story.”

“People look at the image first and that’s what forms the impression and I don’t think we treat those images with that understanding in mind,” she says. “Newsrooms would be better served if they understood the visual language of this digital space.”

As for the women in the stock photo, Roessler says they were supporters of the Muslim preacher Pierre Vogel at a public gathering near Frankfurt, Germany. Though their image has appeared in outlets across the globe, in stories about places ranging from Austria to Denmark and now Quebec, their identities continue to be unknown.

About the author

Maria Iqbal is the 2017/18 editor of Ryerson Review of Journalism

Great piece, Maria.