A perfect August evening. The sun is setting slowly over Larchmont Harbor as the scattered yachts create ripples on the waters of Long Island Sound, their floating frames swaying in the wind. Sulome Anderson is running late, as usual. She hurries down the pavement outside the Larchmont Yacht Club to make it in time for her friend’s wedding in 2016.

The outdoor ceremony is coming to a close as a panting Anderson arrives, quickly blending into the crowd of sharp suits and flowing dresses. Shortly after, as guests mingle inside large white tents, attendants whisk by with plates of delectable hors d’oeuvres and champagne-filled flutes.

Frank Sinatra’s voice drifts out from the speakers, but is overpowered by loud laughter, conversation, and the sound of glasses clinking. Anderson joins the merrymakers, toasting to the couple’s future and feeling relaxed in her mint-green cocktail dress and fashionable stilettos. She’s walking through the crowd with a plate full of appetizers when: Boom!

The loud blast of a cannon slices through the chatter, and Anderson’s reflexes kick in. She falls to her knees, touching down onto the hot concrete, her plate of beautifully crafted hors d’oeuvres scattering around her.

The boom, it turns out, is a ceremonial accoutrement—the yacht club’s customary exclamation point on a wedding well-executed. Everyone around Anderson seems to know this and, as she falls to the ground, they erupt into cheers and impromptu toasts, then turn quizzically to her. Silence. It takes a few seconds for Anderson to realize she isn’t in danger. She picks herself up, dusts herself off, and adjusts her dress, mumbling embarrassed apologies.

A couple of months earlier: a different setting. Anderson—a freelance journalist with a reputation for telling evocative stories about topics like Hezbollah, Sunni child soldiers, and human rights issues—is walking on the dry, cracked land outside an outpost near ISIS territory, outside the northern Iraqi city of Kirkuk. Nearly 30 armed Kurdish fighters accompany her, as part of an assignment that involves shadowing the Hamawand—a tribe with a historical reputation for resistance, including the Ottoman Empire, the British, Saddam Hussein, and now, ISIS. She was told about this militia by a contact from Beirut, and her curiosity to report in Iraq led her to write a profile about them for Vice.com in June 2016. Her clothes cling to her body in the stifling heat of the desert sun. With each step the sounds of gunfire grow louder, bringing the group closer to the frontline of the war.

She hears the rocket whizzing above her head before she sees it. Landing 55 metres away into a nearby school, Anderson waits for the explosion, but there’s only deathly silence.

Trying to stay composed, she feels her body trembling. The militia fighters with whom she is travelling open fire, even though the rocket is a dud. “I just concentrated on holding my camera and taking pictures and on not freaking out,” she says now.

“You forget how traumatizing it is to see people die.”

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is well-known, but its depth and long-term effects are often not fully understood. It develops after someone faces or witnesses a traumatic event, which could be combat, sexual assault, or a near-death experience. The most common symptoms are intrusive thoughts, nightmares, flashbacks, and emotional and physical reactions to triggers.

Using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), psychologists would consider Anderson’s cannon reaction to be an example of Criterion E—one of eight levels of PTSD—in which a person shows signs of heightened or startled reactions and hypervigilance. For Anderson, sounds of gunfire and sights of suffering became common, and that story-book wedding reception at a sophisticated yacht club was when she realized she hadn’t escaped them.

According to the manual, PTSD begins with the traumatic experience itself. Once individuals are exposed to trauma, they may be identified under Criterion B (intrusive thoughts, nightmares, and other internal and distressing symptoms). If things don’t resolve at that stage, it leads to Criterion C (avoidance of trauma-related feelings and reminders). Criterion D is a wave of negative thoughts, which affect the individual’s mood, interests and general outlook. Criterion E is the beginning of physical symptoms: hypervigilance, aggression, difficulty sleeping, or startled reactions. If the symptoms last longer than a month, a person can be identified to be in the Criterion G state, which can be functionally impairing.

Laura Kasinof is an American reporter and author of Don’t Be Afraid of the Bullets: An Accidental War Correspondent in Yemen. She was living in Yemen when she started reporting on the 2011 Arab Spring for The New York Times. Focused on getting stories, Kasinof didn’t consider the negative impact on her mental health until she realized she needed treatment for PTSD after returning home from Taiz, in southwestern Yemen, covering the takeover of the city by anti-government forces.

Kasinof found herself within a turbulent crowd, with hundreds of civilians frantically running. She watched—and reported—as the military shelled civilian areas, feeling numb. She had no guilt, no panic, no sense that something was wrong. That numb feeling tempted her to intentionally put herself in harm’s way when reporting “just to feel something.”

Death and destruction were commonplace in Kasinof’s new world; she would often shut off her emotions to avoid falling into depression, “otherwise you’re not going to go there every day, it’s too sad.” But she noticed she was slowly beginning to have difficulty switching them back on again.

“You forget how traumatizing it is to see people die,” continues Kasinof, adding that these stories are important to tell, but she needs to be healthy if she is to continue telling them.

Many people believe that for PTSD to occur, the individual must directly experience the trauma. That isn’t always the case, according to Anthony Feinstein, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto and a neuropsychiatrist. The symptoms of PTSD would be the same for a journalist or a civilian as they would be for a soldier who physically experienced conflict, he says. PTSD can be triggered after personally experiencing trauma, witnessing it, or indirectly being exposed to it as a first responder. The DSM also states that PTSD could be caused by learning that a relative or close friend was exposed to trauma.

That day in Taiz—only six months into her career as a conflict correspondent—was when Kasinof came to realize that something wasn’t right. The only thought she had in her mind was, “I’ve got to leave this place, something’s wrong with me.”

Once she flew to New York to visit family, she thought being away from conflict would be enough of a break for her to begin feeling like herself again. However, she noticed that she grew angrier and more irritable—what psychologists identify as Criterion E.

Another symptom common for soldiers and conflict reporters is hypervigilance, as Anderson experienced. While Kasinof began to shake that off during treatment, it reappears on occasion.

In the summer of 2017, five years after she last reported in Yemen, Kasinof was sitting in a restaurant near the Caucasus mountains of Georgia, where she was living at the time. A few of her friends were visiting when their conversation was interrupted by the sound of a gunshot. Kasinof’s self-protection instinct kicked in. She jumped up from the table and hid behind a cabinet, even though she knew that many people carry a pistol in Georgia. But in that moment, Criterion E reared its head again.

PTSD among soldiers is a common and much-discussed issue. But it’s fairly new for it to be taken seriously as a concern in the newsroom. In 2002, Feinstein studied 140 war correspondents and found 28.6 percent experienced a lifetime prevalence of PTSD, 21.4 percent had major depression, and 14.3 percent struggled with substance abuse.

When looking specifically at women’s reactions to trauma and anxiety, Feinstein found that female conflict correspondents are “a highly select, resilient group” within the gender population. According to the American Psychological Association, women have a higher chance—often twice the chance—of developing anxiety than men. This, Feinstein believes, can be caused by gender differences in brain chemistry, specifically in levels of serotonin, which contribute to responsiveness during periods of stress and anxiety. However, he adds, it can also be due to social upbringing since women are more conditioned to fully experience and embrace their emotions, while men are conditioned to suppress them.

In his study, “War, Journalism, and Psychopathology: Does Gender Play a Role?” and his book, Journalists Under Fire: The Psychological Hazards of Covering War, Feinstein found “no statistically significant gender differences in frequency of substance abuse or symptoms of anxiety, PTSD, or depression.”

Historically, conflict reporting has been an exclusive boys’ club. At the time of the First World War, women were generally looked down upon if they showed interest in writing outside of the lifestyle section. But, gradually, more female journalists began breaking into the field through persistence and with the help of strong role models, who had blazed a trail for them—women like Kit Coleman, Martha Gellhorn, and Dickey Chapelle. While male journalists might focus solely on conflict, women reporters may be able to analyze the effects of the war and speak to women and families, gaining access into interviewees’ homes and personal stories.

In Anderson’s case, she wasn’t inspired to pursue war reporting because of a trailblazing woman. Instead, her role model was a man—specifically her father, Terry Anderson, a renowned conflict correspondent for the Associated Press. He started his career in 1974 in Asia and Africa, and eventually became the chief Middle East correspondent in 1982, based in Beirut. What made him a household name, however, was the moment when he became a story. On March 16, 1985, Terry was kidnapped while walking down a street in Beirut, having finished a game of tennis. His abductors—members of a Shiite militia affiliated with Hezbollah—grabbed him and pushed him into the cramped space behind the front seat of a car.

Anderson’s kidnapping lasted nearly seven years. He was a hostage for Hezbollah, who unsuccessfully tried to use him to drive U.S. military forces from Lebanon, leaving him with physical and psychological scars. Sulome met him for the first time as a curious six-year-old, when he was finally released. He was consumed by PTSD. He was distant and unaffectionate, not how she’d imagined him, as she described in her memoir, The Hostage’s Daughter: A Story of Family, Madness, and the Middle East. What she didn’t realize until later in her life was how deeply her father’s PTSD affected her psychologically, specifically through her struggles with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) and substance abuse.

But the experience also drew her toward conflict reporting. After attending Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, she began freelancing overseas. Her work has appeared in The Atlantic, Vice, Esquire, Vox, and Newsweek, among other publications.

“These stories need to be told,” she says. “I really want to make people care about the human beings suffering from war.”

Many journalists take hostile environment training in order to learn how to properly react when reporting in war zones, but an average course represents a huge cost often not feasible on a freelancer’s income.

The training programs expose journalists to certain situations, like violent protests or kidnappings, to train them to remain calm and prepared if they actually find themselves in such situations while on assignment. They allow reporters to identify their own vulnerabilities and make safe decisions in the field.

Adam D. Terpstra, a Toronto-based psychotherapist and social worker who has focused on the study and treatment of trauma, says proper training before being dispatched into a conflict zone can help prevent PTSD.

“Part of PTSD is the interpretation of the inescapability from the shock or the event, which would allude to the idea that the person does not have ways to understand what’s going on around them,” says Terpstra. “If you cannot navigate through that, you become arrested in the trauma; that’s where PTSD blooms.” But this training can cost up to $4,000, and with the small compensation freelancers receive for their stories, and having to pay for travel costs and lodging, that—along with a trained security guard—is simply not in the budget.

In April 2011, Kasinof was in Sana’a at the centre of an anger-fuelled protest in a tent city. What started off as a demonstration with 5,000 people grew to 10,000 as the day went on. The political revolution against the corrupt Saleh government wasn’t settling and the Yemeni citizens had a fiery anger that couldn’t be extinguished.

A group of around 400 youths removed themselves from the crowd and marched outside the busy protest camp. Government forces instantly surrounded them and, unsure whether the group was going to become violent, released tear gas.

Kasinof heard the bullets before she saw them. Just from the distinct sound of the gunfire, she knew that whoever was shooting was standing from the second floors of nearby homes and buildings. She said she can still tell the difference today between a sniper shot from ground level and one from above.

The protest camp was in a state of chaos. Citizens ran in all directions, scurrying for cover like mice. Panic washed over her as she heard the cracks of unseen sniper bullets.

Kasinof had two options: Run, and face the chance of being caught and deported. Or hide.

Her eyes scanned the streets. She spotted a small shack beside a mechanic shop, and sought shelter there. The structure was made of a thin material; she wasn’t sure if it was corrugated metal or some kind of cheap wood. It stood at about one metre by three metres, and was too small to stand up in. Squished beside her were six others also seeking protection.

Kasinof could taste and feel the tear gas slithering through cracks and openings, and she hoped the shack would hold up.

Thirty minutes later, the chaos subsided.

“I really want to make people care about the human beings suffering from war.”

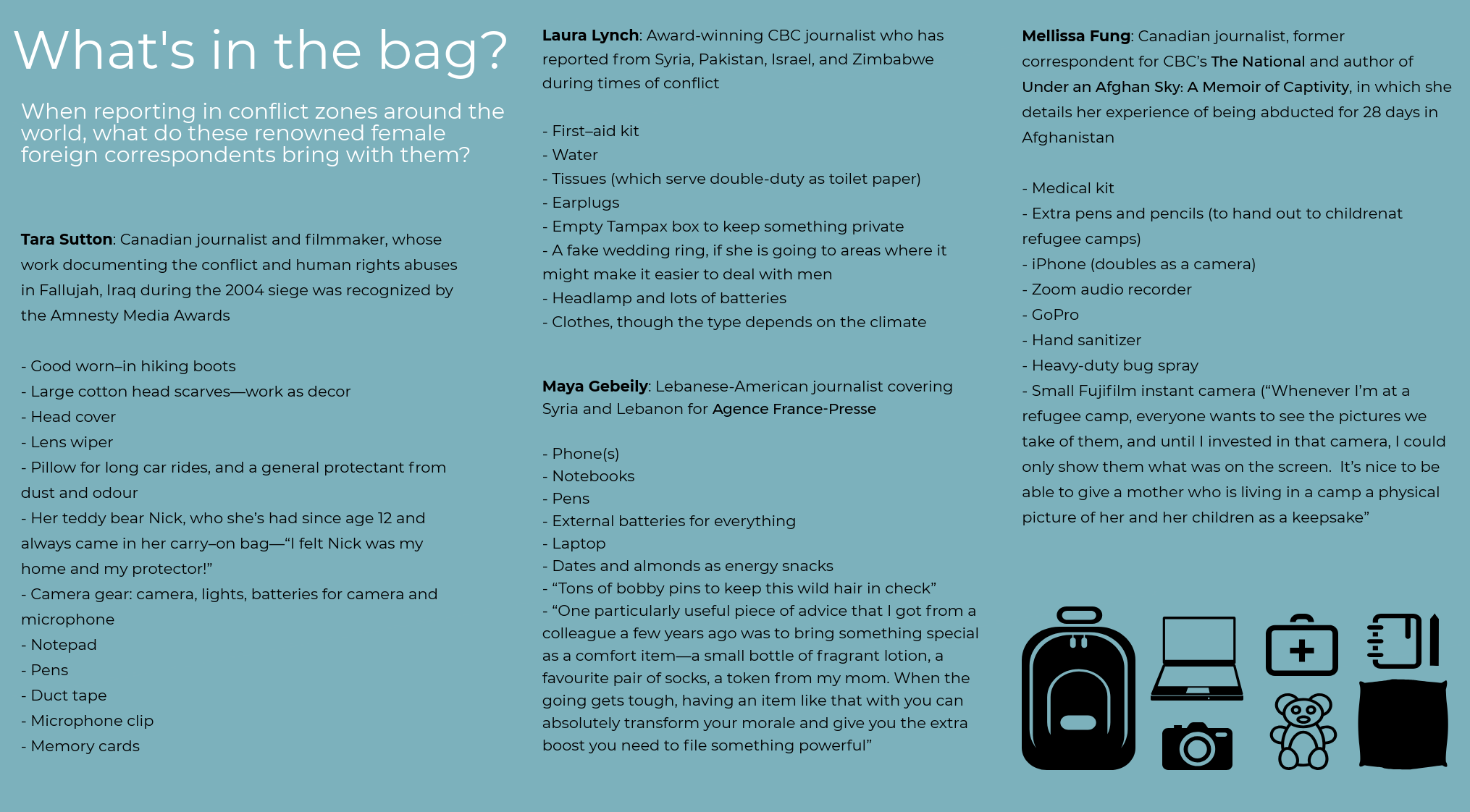

Maya Gebeily would likely have had a better response plan had she been in Kasinof’s position. As a staff correspondent in Lebanon for Agence France-Presse, conflict training was a mandatory requirement when she was tasked to cover conflict there. She also had a safety kit, which included a flak jacket, helmet, first aid kit, BGAN (a portable satellite router), and a satellite phone.

In February 2016 Gebeily underwent a four-day training course run by French security forces just outside of Paris. She went through simulated conflict scenarios that involved dealing with hostile people, physical and sexual assault, identifying weapons, and an overnight, five-hour mock abduction—all to understand how she would react in a high-stress situation.

The kidnapping scene took her by surprise, even though she knew it was just a training scenario. Told to go into a training warehouse for a lesson on bullet identification, she was taken off guard when four men burst in and covered her head with a dark hood. Gebeily and her colleagues were then pushed into a truck and relocated.

Although she knew it wasn’t a real abduction, her body and mind were reacting as if it was. To her own surprise, however, she remained calm. She felt as if time had slowed down and the only thoughts running through her head were about finding ways to escape.

It was cold outside. She was repeatedly reminded of this when she and her colleagues were forced outside of the warehouse, only to have buckets of cold water dumped over their heads. The training began around 11 p.m. and they weren’t released until around 4 a.m.

“Even if you know that what’s happening around you when you’re doing the training is not real, you at least get the sense of what it would be like, so that if it happens for real, it’s not the absolute first time,” she says.

“I had a magazine offer me $100 when I first started out for a 2,000-word story in which I went to the Syrian border. I was risking my life; that’s humiliating.”

Anna Therese Day, an award-winning freelancer, media activist, and founder of the organization Frontline Freelance Register (FFR), was slowly drowning in guilt and PTSD as she began making a name for herself in the Middle East. Normal interactions became exhausting and she began slipping into a dark depression. The question, “How am I helping anyone?” kept eating at her.

During her time reporting on the Syrian Civil War, she became increasingly cynical about whether “journalism actually helped.” She had spoken to many families and written hundreds of articles throughout her career, but she wondered if the impact on these people’s lives and well-being was insignificant.

During these darker moments, what helped her re-centre and come up for air was the idea that while journalists are working towards helping change lives, discourse or policy, “it’s also enough to do your best work, honour individual families, and contribute to the broader mosaic.”

When dropped into an extreme situation with no buildup or preparation and then quickly pulled back out, the mind has difficulty grasping whether you are really in danger, says Terpstra. Gebeily’s kidnapping wasn’t real but, in the moment, her survival instincts switched on and it all became real. This is a similar experience to that of journalists who are “parachuted” into war zones. Because their minds can’t fully process what is happening, one of the only emotions that resonate with them is guilt.

This guilt is often rooted in the fear of putting colleagues or fixers in danger, along with the unwavering reminder that, as journalists, they are visiting these war zones only to report, but cannot help. This state of chaos is physically and mentally inescapable for many civilians, but for a journalist the experience is temporary.

“There’s no buildup. You’re dropped in, you’re there for three weeks, you experience it, and then you leave,” says Terpstra. “Guilt might be the entity the mind can grapple with and try to make sense of the scenario.”

To avoid this feeling of guilt, journalists often try to “turn off” their emotions when speaking to civilians who are gravely affected by the conflict but, according to Anderson, a human’s natural sense of empathy stops them from being able to do so and their work suffers if they ignore that sense of empathy. While some reporters try to “detach” from their emotions so they don’t “burn out,” emotions often seep through anyway.

The nature of conflict reporting puts freelance journalists at a high risk for PTSD, but even those with full-time bureau positions are vulnerable. Stephanie Nolen, The Globe and Mail’s Latin America bureau chief, says that while her paper has a few services to offer its foreign and conflict correspondents, they are not offered unless the reporter asks for help.

Nolen is currently based in Brazil, but her career has taken her to over 80 countries, including the Democratic Republic of Congo, India, Afghanistan, and Sudan. Despite her long career across multiple conflict zones, she has never been offered help. An editor asked her “Are you fine?” once, about 15 years ago, but this was the only time anyone has ever checked on her.

“The assumption just is that we’re all fine,” she says. “No one’s ever checked in with me to see what I needed, I think it would be on me to ask. But then, of course, one of the things that happens is that you become unable to ask. That’s a problem and I think we should do it better.”

Nolen recently took part in the Dart Center’s Ochberg Fellowship, where she raised her concerns about the way PTSD is handled and treated in newsrooms. She was made aware of existing services at the Globe and in the industry in general, but these services’ lack of advertising is a problem in itself.

In the absence of support from their publications, journalists tend to create informal solutions, turning to each other for help or to professional guilds for assistance—organizations like the Canadian Journalism Forum on Violence and Trauma, the Rory Peck Trust, the International Women’s Media Foundation, A Culture of Safety, and the Frontline Freelance Register.

With the help of IWMF, for example, Kasinof was finally able to receive hostile environment training.

“You wouldn’t send paramedics or firefighters to the field without training,” says Jane Hawkes, co-founder and executive producer of the Canadian Journalism Forum on Violence and Trauma, adding that other first responders have been quicker than media companies in establishing systematic training and trauma support.

FFR is also an international organization specifically designed to create a community for freelancers. Launched in June 2013, it provides training resources and a support system to freelance conflict reporters, but also lobbies for change in the industry to improve working conditions for independent journalists. It’s the only organization run for and by freelance journalists.

In the last few years, access to resources has been a challenge for the entire journalism industry, not just freelancers. Publications and media companies now have much tighter budgets, and content creators often find themselves fighting for compensation. Freelancers find themselves easy targets of exploitation when taking dangerous risks to complete an assignment.

“I had a magazine offer me $100 when I first started out for a 2,000-word story in which I went to the Syrian border,” Anderson says. “I was risking my life; that’s humiliating.” She eventually talked her way up to $250, but that it was a real struggle getting to that figure.

Anderson surprised herself when she reacted as she did at the Larchmont Yacht Club at the boom of a cannon. She said she hadn’t realized that she had been so affected by her experience of reporting in conflict zones. While Anderson had a history of borderline personality disorder (BPD), she believed she knew how to handle her emotions.

She now recognizes the long-term impact of her conflict reporting career. Loud sounds still scare her and she always keeps an eye on the exit anywhere she goes.

Now, she’s calling for a more mainstream conversation about PTSD in journalism.

“It’s a real problem and the problem is that people don’t talk about it.”

About the author

Karoun Chahinian was the print production editor of the 2018 issue of the Ryerson Review of Journalism