Edna Staebler’s lawn is pretty well-kept for a home that’s no longer lived in. In the summer months, her nephew Jim Hodgson swings by to mow the grass and shoot pool with friends. When no one’s around, the pool table hides under a tarp a few feet away from the shore. It’s a new development since Hodgson and his sister, Barbara Wurtele, took full ownership of the green cottage that once belonged to the late award-winning magazine writer. Staebler’s ashes were scattered across the lawn so that she would always be at Sunfish Lake—about 10 kilometres west of Waterloo, Ontario.

The sounds of schools of minnows and the splashing of bigger fish trying to catch them interrupt Kevin Thomason as he shows me around. He became Staebler’s next-door neighbour in his late twenties, remained there through the final decade of her life and still lives there today. He brought her mail, and Staebler made sure he always had fresh muffins. He became the grandson she never had.

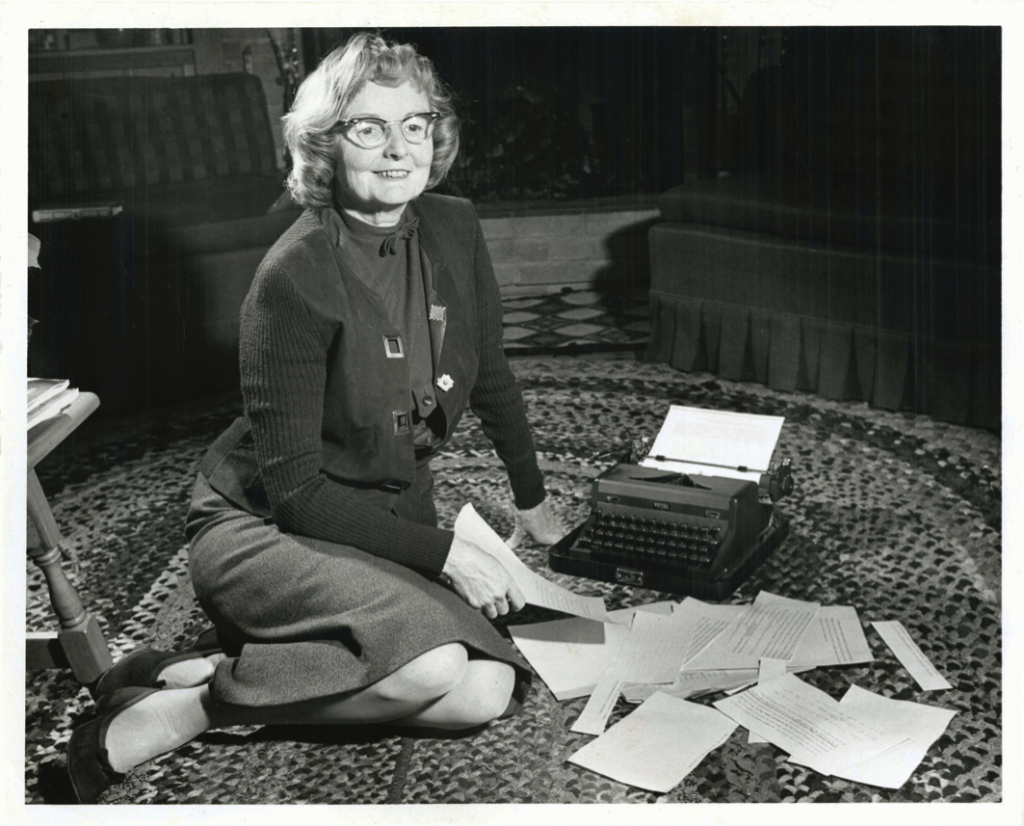

When they met, Staebler was a small woman with horn-rimmed glasses and short, white hair, which she always cut herself. She had a small mouth with an overbite, noticeable when she smiled, which was often. She moved quickly and drove fast. Thomason could hear her car coming down bumpy, unpaved Cedar Grove Road at full speed. Though introverted, spending hours hunched over her typewriter, she loved people. Her writing, always focused on real characters, reflected this. “Edna influenced everyone she met,” says Thomason, “and everyone she met influenced her.”

From the deck of Thomason’s small log home, I can see Staebler’s cottage through the trees. He couldn’t decide on lunch, so he asked himself what Staebler would do: soup with tomato sandwiches. Everything is local. Thomason suggests we sit outside, “even though it’s snowing.” For a warm November day, this seems odd, but he’s referring to the pine needles that land in his soup. He eats them anyway, and I follow his lead. They add flavour.

Almost a decade after Staebler’s death at age 100 on September 12, 2006, the popularity of her cookbooks, including Food That Really Schmecks, and the influence of the annual Edna Staebler Award for Creative Non-Fiction overshadow her pioneering magazine writing. Few people today are aware of the many eloquent pieces she wrote between the end of the Second World War and the fall of the Berlin Wall. Though she was not formally trained, her intuitive, immersive reporting deserves the same respect as the work of her journalistic peers Pierre Berton, Sylvia Fraser and Peter Gzowski.

Staebler was born Edna Louise Cress in Berlin (now Kitchener), Ontario, in 1906. She graduated from the University of Toronto with a bachelor of arts degree in 1929 and received her teaching certificate soon after. Her career in education was short-lived: just six months in, she was let go for taking students outside to do somersaults—an activity deemed unladylike. Her friends joke about the irony in the existence of Edna Staebler Public School, which opened in Waterloo in 2008, but Staebler inspired the school’s core values: compassion, writing and environmentalism. “She got fired and now has an entire school named after her,” says Thomason. “She would think it’s such a hoot.”

In 1933, she married Keith Staebler, whom she had dated throughout university. She often wrote in her diary about her love for Keith, but the marriage began to fall apart toward the end of the Great Depression—although they didn’t divorce until 1962. He became an emotionally abusive alcoholic who thought writing was a waste of time for a woman. He wasn’t alone. Her family also discouraged her dream of becoming a published writer. Staebler obeyed the naysayers for the first 40 years of her life, until a trip to Nova Scotia in August 1945 broke the spell.

She was driving through the east coast with friends, including one who had professed romantic intentions. Fed up with the advances, she asked her friends to pull over. Staebler got out and stood alone, unafraid, at the side of the road in Neil’s Harbour. She wandered into the fishing village, where there were few souls, one store, no hotel and no phone. She belatedly discovered her innate journalistic curiosity.

For many, being alone in the middle of nowhere would be terrifying, but for Staebler, it became a story opportunity. For the next three weeks, she immersed herself in the lives of the locals, mostly immigrants from Newfoundland (not yet Canada’s 10th province). She lived in their homes and ate their food, indulging in what Gay Talese later described as the fine art of hanging out. All the while, she wrote progressively longer, observation-filled letters to her husband and friends.

Staebler’s first inclination was to turn her copious notes into a novel. Eventually, unable to sell the story as fiction, she decided to polish it into a magazine feature. Once she finished, she drove to Toronto and marched into the Maclean’s office to hand-deliver her manuscript. She had no experience, but managing editor Pierre Berton saw potential in her writing. Maclean’s offered her $150 for a shortened version of the story about the fishing locals, and “Duelists of the Deep” appeared in the magazine in 1948.

Staebler’s writing is rich with detail. In one scene, she described meeting a swordfish:

A leviathan was stretched from the deck to the top of the fifteen-foot pole! I was seeing my first swordfish. It was stupendous! The body was round; the skin a dark purple-grey, rough one way, smooth the other like a cat’s tongue; the horny black fins stood out like scimitars, the tail like the handlebars of a giant bicycle; but the strangest thing was the straight, pointed, sharp-sided sword which was an extension of the head—an upper bill more than three feet long. As the rope was slowly released, the men guided the creature down to the dock.

She used simple comparisons, like linking the “ruddy-faced men” in the village to “broad-billed birds in their strange caps with wide visors six inches long,” to bring vivacity to the story. Numbers, such as the 634-pound swordfish carcass, lent precision. Dialogue—including bad grammar—made the characters authentic. And as she was a primary character in the story, her voice remained present.

Here’s her encounter with a child who offered her the sword-fish’s eyeball:

“Take it,” he said.

“You mean you’re giving it to me?” “Yes.” (Not yeah.)

I couldn’t spurn a gift; reluctantly I held out my hand. The boy placed the crystal gently on my palm. It felt cool and tender as a piece of very firm jelly or a gumdrop that has had the sugar licked off it.

“What should I do with it?”

“Take it ’ome and put in sun and it’ll turn roight ’ard. Be careful not to break ’un.” I held it almost reverently. It didn’t smell like fish either.

The stories that followed “Duelists” similarly put readers inside a subculture, a method familiar to anyone acquainted with Tom Wolfe’s New Journalism articles for Esquire and New York magazine in the mid-1960s. Fortunately, Berton and others knew talent when they read it. Staebler became a regular contributor to some of the biggest Canadian magazines of her day: Maclean’s, Saturday Night and Chatelaine.

Two years after “Duelists,” Berton assigned her to write about the Old Order Mennonites living in the Kitchener area. After visiting the general store to ask about a willing family, she lived with the “Martins,” (the name used to protect their privacy) and immersed herself in their lifestyle and traditions. “How to Live Without Wars and Wedding Rings” was as detailed as her first story.

Staebler’s participatory reporting made her a pioneer of what has come to be known as literary journalism. Her technique was to knock on a stranger’s door and ask to stay. In a 1952 Maclean’s story about Hutterites in Alberta, she jumped on a bus to Waterton Lakes with a plan to find a way into the community. En route, she met a woman from the Old Elm colony who said she could stay with her for a few days.

Staebler’s ability to make others feel comfortable was her ticket into the lives of perfect strangers. Bruce Gillespie, who published a 2015 academic study of Staebler’s magazine writing, says her approach made sense from a journalistic point of view, but for her it was simply the only way. Many of today’s reporters wouldn’t always think to live among their subjects for a week—a quick visit and maybe a few phone calls usually suffice. “It speaks to her character,” says Gillespie, “that these people who took active interest in not showing their community life to outsiders kept saying sure.”

Close friends agree. Her personality played a crucial role in securing access. “She was so interested that they opened up to her and told her all she wanted to know,” says cookbook writer Rose Murray. “That’s how she got her stories.”

But what set her work apart was her subjects. She took an interest in ordinary people from different cultures and ethnicities living in isolated areas—Italian immigrants in Toronto, descendants of slaves living in Nova Scotia, a miner’s family in northern Ontario. Her stories showed Canada’s diversity, something most writers at the time weren’t doing.

To Gillespie, who teaches at Wilfrid Laurier University, finding these magazine features in the archives at the University of Guelph was a revelation. Her magazine work isn’t as easily retrieved as her cookbooks, and it’s understandable why the latter became so well-loved. Her first, Food That Really Schmecks, published in 1968, sold tens of thousands of copies and turned into a series, including Schmecks Appeal and More Food That Really Schmecks. Her cookbook writing wasn’t far removed from her literary journalism. The storytelling involved real-life characters and included anecdotes from her time living among the Mennonites in the 1950s. She borrowed recipes from an Old Order Mennonite friend, Bevvy Martin. In the beginning of the Vegetables section in Food That Really Schmecks, she opened with a scene from Martin’s garden:

There isn’t a Mennonite farm that hasn’t a garden near its sprawling farmhouse. As soon as the well-manured ground in Bevvy’s garden has been cultivated in spring, she plants seeds in long neat rows; then she looks out of her kitchen window to watch the vegetables grow. “Quick, Salome,” she’ll call on a sunny June morning, “I think the beans came up last night.” And out they’ll both run to rejoice at the promise of coming abundance. Every day they keep watching, comparing growth progress with neighbours and friends. “My beets are slow this year,” one will say; or “I don’t think my cauliflower will amount to much,” or “There’s going to be a bumper crop of peas.”

In the introduction to the Pies and Tarts section, she quotes a Mennonite man named Amsey—“And that really schmecks!”—to describe a peach pie made with the peelings. The exclamation, describing something superb, became the series’ inspiration.

After hearing that many people read her cookbooks before bed each night, Staebler joked that she was the cause of the country’s declining birth rate. Never a cook herself (though she loved food), Staebler laughed at mistakes in early editions of her recipes. Kathryn Wardropper, sales representative at HarperCollins, administrator for the Edna Staebler Award for Creative Non-Fiction and one of her closest friends, says Staebler’s true passion was writing. “Cooking,” she says, “had nothing to do with it.”

No one intimidated Staebler, and certainly not lawyers for billion-dollar cookie companies. Don Sim, a Toronto lawyer representing Procter & Gamble (P&G), which had recently purchased the baked goods company Duncan Hines, was about to find that out. In 1984, he called Staebler to ask if he could visit Sunfish Lake. P&G had filed a suit against Nabisco (the National Biscuit Company) for infringement of a patented formula for crisp, chewy cookies. Nabisco, the cookie industry’s top company, commanded 80 percent of the market.

The argument between the two corporations centred on rigglevake cookies (Pennsylvanian Dutch for “railroad cookies”), a combination of molasses and old-fashioned sugar cookies. The swirly design of the two types of dough made them look more exciting than they tasted, but that wasn’t the point. Nabisco argued that P&G couldn’t patent the recipe because it appeared in Food That Really Schmecks, and published recipes cannot be patented. Sim’s job was to prove that P&G’s cookies were different from rigglevake cookies, so he asked to watch Staebler’s Mennonite friends bake, promising to pay them for their time. Staebler was protective of her friends, but was also pretty sure they would be happy to make money. This began a strange relationship between the Mennonites and lawyers representing both major companies, hoping to prove the rigglevake recipe was, or was not, crisp and chewy. Many cookies, 182 days of pretrial testimony and 200 witnesses later, the case was settled out of court.

Staebler’s Saturday Night feature about the episode, “The Great Cookie War,” was in her signature style, using characters to show exactly what happened. She described Sim plainly as “six feet five inches tall and weighing over three hundred pounds,” but then, with more colour, she “wondered which of my chairs would hold him.” Her point of view was vital. She didn’t understand all the nuances exactly, or how her Mennonite friends played a role, so she became the naive narrator to guide readers and write about patent infringement in a way that wasn’t impenetrable and boring. Staebler also refused to be boring in her personal life.

In her younger years, she escaped the confines of her marriage with travel through Europe and across Canada. In university, she had been inexhaustibly social. Alyson King, who teaches at the University of Ontario Institute of Technology, was drawn to Staebler after reading her published diaries and decided to study her U of T years, 1926 to 1929. King was studying the experience of women in universities from 1900 to 1930, a period with what she refers to as the second generation of university women. She wanted to focus on what being students was like for them. “I had the feeling,” King says, “those years were when Edna really could be herself.” Wardropper was impressed that Staebler had obtained her degree in the ’20s and once asked what was the most rewarding part. Staebler replied, “Partying.”

Wardropper has smile lines around her eyes and thin, silver hair, which she wears long. She reaches out to touch my hand while I’m talking to show me that she’s listening. She was holding Staebler’s hand when she died and feels lucky to have been friends with her for so many years. “If she loved you,” says Wardropper, “she loved you very, very deeply, and there were many people she did love.”

The two met in 1978 while putting together a float for the Kitchener-Waterloo Oktoberfest parade. With it, Wardropper wanted to showcase inspirational women in the community, and asked Staebler and a few others to ride. Staebler sat on a pedestal wearing a black and white tweed coat, smiling and waving despite the rain. “I would have thought she was the queen,” says Wardropper. “I fell in love with her.” After the parade, the two often drank afternoon tea in the sunroom at Sunfish Lake until it got dark. They talked for hours and lost track of time as night fell. Apart from writing, having visitors over was Staebler’s full-time job. On any given day, people—from Neil Young’s mother to famous writers like Berton and W.O. Mitchell to a homeless ex-convict—were in her living room. When she turned 100, nearly 500 people came to her birthday party at Wilfrid Laurier University, and her funeral attracted just as many. Writer Ardy Verhaegen says a trip to Staebler’s cottage was like a soiree.

Staebler had a calendar in her kitchen with visitors listed, often with several names pencilled into the same box. Many walked down the path to knock on the door, and Staebler would always shout to come right in. Sitting in her big chair with a homemade blanket draped over the back, she was always knitting. Never idle, she kept busy handmaking toy mice for cats that were distributed locally. She used different colours of yarn, and her sister Ruby later stuffed the bodies with catnip and sewed on the nose, tail, ears and whiskers at her home in Peterborough, Ontario. By the time Staebler died, she estimated she had made tens of thousands of the mice.

Staebler always owned cats. She died in her sleep with a fat tuxedo named Oliver sitting on her thin knees. She used to love Rose Murray’s dog Scamp, too, but she didn’t extend the same kindness to the angry possum she caught bothering chipmunks on her property. Thomason recalls seeing Staebler shooing the possum with her cane. She wasn’t afraid and managed to scare it off. “She had phenomenal moxie,” says Wardropper. “She was a feisty lady.”

Staebler’s moxie was evident in the way she stood up for her beliefs. In the final quarter of her life, she started an endowment with Wilfrid Laurier University to establish the Edna Staebler Award for Creative Non-Fiction. First awarded in 1991, the prize honours a Canadian writer, who now receives $10,000 for a first or second book.

Since her death, the university used the money Staebler left to establish a writer-in-residence program as well. During her life, Staebler was astutely aware of her own finances and spoke with Laurier’s president when she felt the university’s investments could be doing better. The president took note. “She looked like a sweet, apple-faced old lady,” says her friend Wardropper, “until she wasn’t happy.”

Staebler had plenty of motivation to establish the award. After spending the first half of her life around people who warned her she’d never make it, she won the 1950 Women’s Press Club Award for the Maclean’s story “How to Live Without Wars and Wedding Rings.” This public confirmation of her talent gave her the confidence to continue and eventually inspired her to create something similar to help others. When the prize launched, Staebler was in her mid-eighties, and the process of determining a winner kept her busy reading the nominated books, usually around 50.

Since her death, others, including Gillespie and Wardropper, have helped choose the winner. At the most recent ceremony in November 2015, Lynn Thomson stood at the podium to accept the award for her book, Birding with Yeats: A Mother’s Memoir. Thomson and her husband own Ben McNally Books in downtown Toronto, so naturally she always thought of herself foremost as a bookseller. “Now,” she said, “I feel like a writer.”

Barbara Wurtele, Staebler’s niece, was sitting in the audience. As Thomson took questions, Wurtele raised her hand to say she used to go birdwatching with her aunt when she was younger. “Edna,” she said, “would have loved your book.”

Staebler was also present at the ceremony, albeit in video form. In an excerpt from Lawrence McNaught’s in-development documentary about her, she talked about the award. Every once in a while she scratched her face with one of her knitting needles. Her voice was quiet and raspy as she described how it felt to finally get recognized for her writing. “I had no confidence in myself,” she said. “Then I won this great award, and I thought, I really am a writer.”

About the author

Sydney Hamilton is Head of Research on the Spring 2016 issue of the Ryerson Review of Journalism

A memory I cherish of Edna Staebler is, in the late 70s, when she was sightseeing in Jasper, Alberta and saw that I was using, “Food That Really Schmecks”, to prepare meals for the staff at Maligne Lake boat tours, autographed it with the line, “To the Gourmet Chef of Maligne Lake.” I still use her title proudly every chance I get.