Lauren McKeon has come full circle.

It’s been 10 years since she graduated from Ryerson University’s undergraduate journalism program, where in her final year she wrote a somewhat controversial feature on The Walrus for the Ryerson Review of Journalism.

The feature was critical about former Walrus editor Ken Alexander’s newsroom, causing some people to question whether it would sabotage her career and certainly any future prospects at the publication.

Yet, McKeon moved into a digital editor role at The Walrus in August this year.

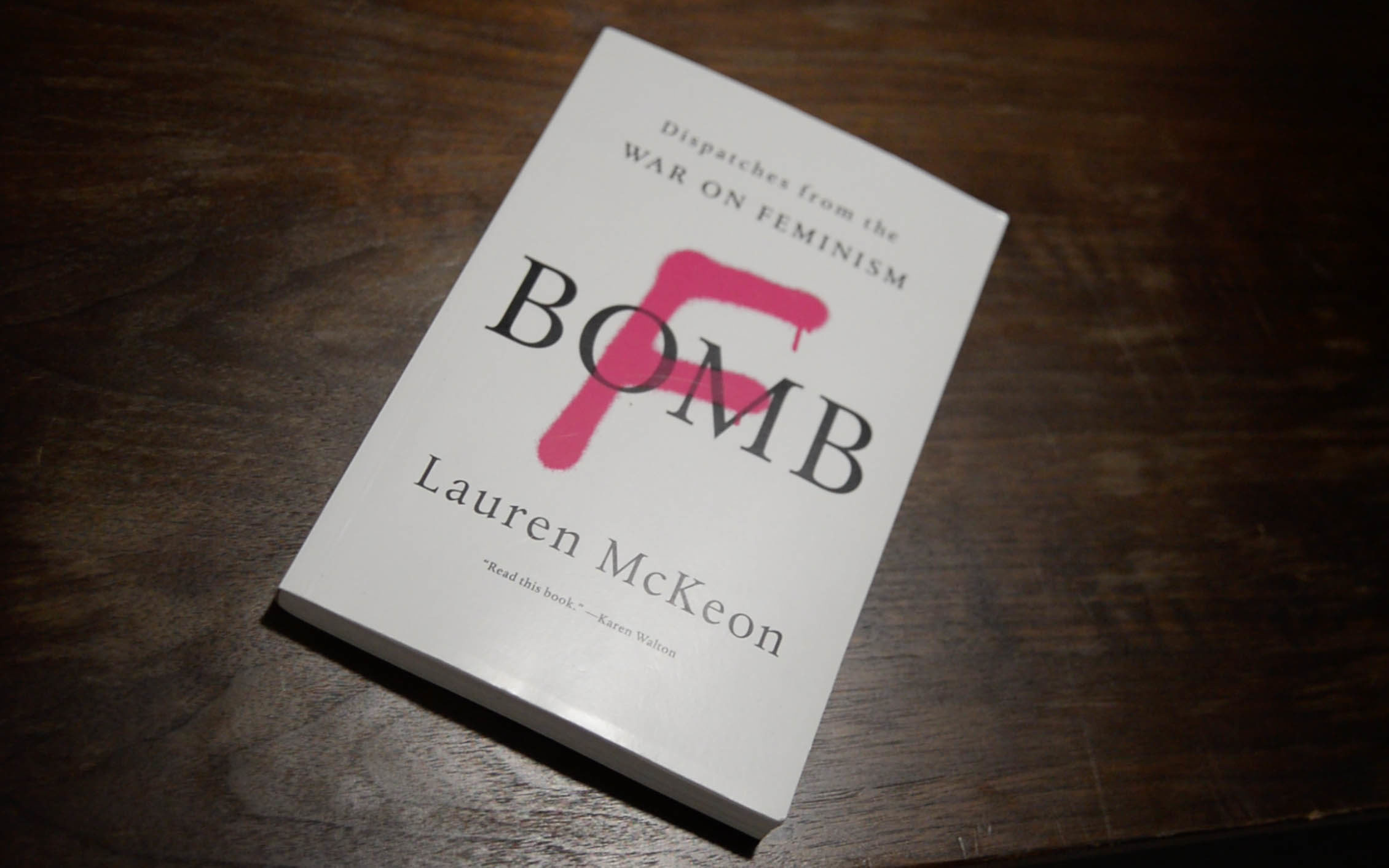

Her journey to this current position includes being the editor at This Magazine, teaching at Humber College, and now juggling a position as contributing editor at Toronto Life as well as her position at The Walrus. And she’s also found time to pen a book, F-Bomb: Dispatches from the War on Feminism, which was published in September.

The idea for a book grew out of her Master’s thesis while completing a degree in creative non-fiction at the University of King’s College in Nova Scotia. McKeon identifies as a feminist and her book focuses on growing trend of anti-feminism among women and covers issues like GamerGate, the Men’s Rights Movement, and reproductive rights. Her career as a woman journalist prepared her to write about feminism, a subject she is deeply engaged in.

Q: When did you realize that you needed to write this book?

McKeon: I wish it were so linear — it’s not. When I started writing F-Bomb in 2014, it was this bubbling of anti-feminism that I saw. What kept me going was the research, was this kind of certainty that we would see it gain ground. When we did see anti-feminism gain ground — certainly in a very sensational way — over the U.S. election and now, I became more and more convinced people would want to know what happened.

Your book is written in first person and has more of a casual tone, using phrases like “WTF” and “clapping back.” Why did you decide to write the book in the way you did?

There’s this perception that feminism is scary, or it’s too academic or that it’s exclusive, because if you don’t use the right language and talk about it the right way, then you might be kicked out of the club. I wanted people to feel they could have a conversation based on the book, and that they didn’t have to be intimidated, [which could help with] breaking down some of the barriers about who feminist books are for.

Right. What was it like for you to have to cover and discuss with so many people, who had such strong, opposing opinions on feminism and sexual assault?

I really try to be a journalist first going into these spaces, and I wasn’t there to convince people of my own politics. I was also there to have my beliefs interrogated as well — I wanted to know the answer to what was going on. It was doubtful I was going to go into a place and become a steadfast anti-feminist, just as it was doubtful that I would go into a place and convince another [person not to be]. I don’t think that was the purpose of what we were there for. I think what allowed me to go into these spaces was being a journalist trying to be fair and thoughtful, and not being there to get into an argument or a shouting match with anyone. I did take a friend to a lot of the events that I went to where I felt like I would need someone to talk to after.

What kind of advice would you give to someone who wants to cover something in depth that they don’t agree with, which might be discouraging or depressing for them?

I think it’s important to ask yourself why you want to do it, and what your own agenda is. If you go in there with an agenda, and you just want to do a takedown of something, or you have preconceived notions and you’re not willing to have an open mind, that’s bad journalism. That’s not journalism. Do the job of a reporter.

I try to be honest with the reader, like “This is what I thought beforehand,” and then “This is what I learned,” “This is what I think now,” and “This is some of the unfair thoughts I have that you may be having too.” For a book, you have more space to do that, but in general it’s about just remembering why you’re there and what it means to be a journalist. Journalism can affect change and inspire discussion, but journalism with a straight agenda becomes didactic.

In your book, you cover intersectionality in feminism and how women may not relate to the word ‘feminist’ because they don’t think it covers their experiences. Have you ever struggled to identify as a feminist because you didn’t think it was inclusive to you?

Well, I’m a white woman, so that’s what mainstream feminism tends to reflect. Feminism needs to interrogate itself and be self critical asking “Who is it really for?” The perception that it’s white women is a valid perception. That criticism is so necessary and vital for the movement to move forward.

I do think age plays a factor too. I’m 33, so not so young, but a lot younger than a lot of the forerunners of the movement. I think that sometimes there’s this sense that [younger] feminists don’t really know what the movement is about, and they didn’t fight for it the same way. I think that there’s this sense that you haven’t earned it sometimes. Certainly I’ve felt that.

You talk about GamerGate and the death threats and doxxing that happened to women who spoke out against it. Have you experienced backlash for writing this book?

I was nervous about that. I anticipated backlash and I haven’t looked at my social media accounts since the book came out. As a woman journalist who has written about feminism before, or even just as someone who has an opinion really, I’ve had death threats and rape threats come over social media before.

So, what is your advice for women journalists who deal with hate like in GamerGate?

I don’t think there’s an answer right now for us on how to deal with that. I don’t think you can engage with a death threat. I think we do have to talk about it. There’s this expectation [of] fearlessness or toughness — that you have to have a thick skin. We have to acknowledge that this toughness, that’s part one of dealing with hate, and that it’s not consistent — I know I’ve been tough and I’ve gone home and been shaking after. I don’t know how to solve it, but I know there’s a way to acknowledge that it’s not easy for us.

You talk about one of your jobs where your editor never seemed to respect you very much because you were a woman. What advice would you give to female journalists starting out who have to deal with this kind of mentality?

I think at the time, I thought I would just prove myself. I was young, I didn’t really know how to dress for the office. There were many things that probably signalled to him who he thought I was — this person who didn’t really belong in serious journalism. I don’t think people like that ever will accept you.

At the same time, there are new avenues opening up and a lot of young women have said, if that system won’t accept me, then I’ll just do my own thing over there, and they’re finding success. Form a community with younger journalists, talk to them, talk to each other, find a mentor within journalism who has gone through it that you could talk to. Don’t let them push you out. Journalism needs more diversity, it needs more perspectives. It has to have those things to thrive in the future.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

About the author

Visual editor at the Ryerson Review of Journalism.