By Aya Tsintziras

Sally Armstrong travels to Kenya. She begins in Nairobi and drives north to Meru. She approaches the Ripples International shelter; the road is lined with colourful plants and flowers. It’s 2011, and she’s here to interview 160 child rape victims, some as young as three, who are suing the government for not protecting them, and for failing to uphold the 2010 Kenyan constitution’s promise of greater equality for women and girls. First, Armstrong speaks to 11-year-old Emily, who tells her about being raped by her own grandfather. Then Charity, who is also 11, and her sister Susan, who is six. For them, it was their father.

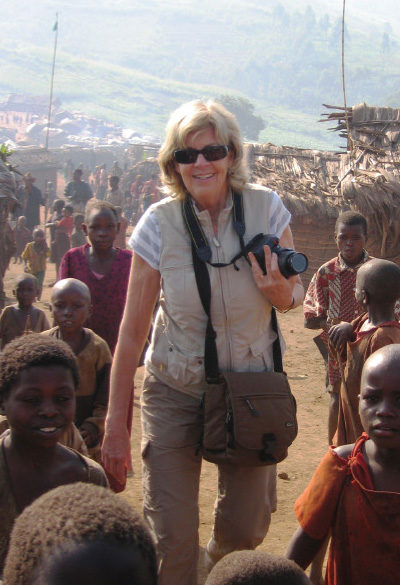

Two years later, despite a bad cold, Armstrong commands the stage during a Canadian Women’s Foundation speech. Tall and wiry, with her signature highlighted blonde bob, she adds to the powerful story from her 2013 book, Ascent of Women. “When I leave these places, their stories play on the back of my eyelids,” Armstrong says in a gravelly voice. “I wonder how they’re doing. Often with my stories I get to go back and see them again.” She explains the issues in her powerful but compact style: Emily’s grandfather raped her believing it would cure him of HIV/AIDS. “It made me sad, but more than that, it made me enraged.”

That anger over injustice has propelled Armstrong’s decades-spanning career sharing the tragic and hopeful stories of women in conflict zones. Every story she writes has two layers: the story, and the story about the story. Often the backstory shows her passion and determination to write, a battle that parallels the ones her sources must endure: while these women fight for their lives and for control over their bodies, she fights to tell their stories—even in women’s magazines. The 70-year-old says she isn’t fighting for assignments now; she gets them because of her expe- rience. But spending even a few minutes with her reveals that the spark is still there. It’s the same spark that led her now-41-year-old son, CBC reporter Peter Armstrong, to write in a scrapbook for her birthday last July, “People often ask me how I felt about my mother going into war zones. I tell them I was more worried about the Taliban than Sally. You think they’re tough? Try sneaking back into our house after curfew.”

Armstrong’s peers deeply admired her bravery when she first travelled to Afghanistan, about six months after the Taliban came into power in September 1996. In the words of Canadian feminist Michele Landsberg: “All those trips to Afghanistan, my god.” Her stories have made more than one young woman say, “I want to be Sally Armstrong when I grow up.”

***

But when Sally Armstrong grew up, she became a high school gym teacher. She was raising two young children in the Toronto suburb of Oakville, and was pregnant with her third, when her husband’s boss’s wife gave Armstrong’s name to entrepreneur Clem Compton-Smith, who was launching a magazine. She thought she wouldn’t get hired. She did. That was the start of Canadian Living, and the birth of Armstrong the journalist.

Listed on the masthead under “special projects,” she wrote about exercise and family for the magazine (which was later bought by Telemedia and then Transcontinental). In the inaugural issue, in December 1975, Armstrong’s story, “Leave me alone… I’m stuffing the turkey,” featured lines like, “Joe Jagger brags to his wife he’s just done nine laps of the track. So what! His wife’s nine laps of the laundry room may be more trying.”

A November-December 1976 story had her lamenting her frantic race to get ready for Christmas every year, comparing her more low-key decorations to her sister’s perfect tree and purple velvet angels with another joke: “When I invite people for a Christmas drink, it doesn’t come with a tray of goodies that look as though they came from a church bazaar. It comes with a block of ice and a napkin.”

For a decade, Armstrong developed her skills as an editor and writer. Then, in 1986, she wanted to profile Sister Theresa Hicks, a lay sister from British Columbia who was attempting to improve the health of impoverished people in Monrovia, Liberia. Armstrong persuaded her editor, Judy Brandow, to take a chance on her and on the story. She got the assignment—and the budget—to fly to the West African nation. “That was my first taste of conflict, and of women’s issues that really matter,” she says. “I wish I hadn’t said that. All women’s issues matter, but it was my first taste of women’s issues that are very hard to turn around.” It was also the beginning of Armstrong’s practice of creating strong, decades-long relationships with women overseas—she’s still in touch with Hicks today.

In 1988, after becoming associate editor of the magazine, Armstrong left Canadian Living to become editor-in-chief of Homemaker’s, a sister Telemedia title that had been around since 1966. She held the position until 1999, and it’s where she found her voice. “We were basically breaking all the rules,” she says. “We were a subversive little magazine that served up lasagna on one page and tried to change the world on the next.”

Although she credits legendary Chatelaine editor Doris Anderson for bringing serious stories to women’s magazines, she took it to the next level by adding international coverage. Anderson’s belief that, if you have readers, you can do the stories you want, was something Armstrong took to heart. And former colleagues say her optimism and energy inspired the staff to push themselves, leading to the publication’s golden era.

In 1996, when interviewing intern Jennifer Elliott at a coffee shop after a permanent position had opened up at the magazine, Armstrong asked, “Do you want my job?” The intern said, “Yes, someday.” It was the right answer—Elliott landed a job as an editorial assistant.

“She had high expectations of her staff,” says Cheryl Embrett, who started at Homemaker’s as a copy editor, then moved up to senior editor. “Sometimes I felt like Sally thought we were working at a newspaper. She wanted the best story. She didn’t care about magazine deadlines.”

Armstrong left Homemaker’s in 1999 to get her master of science degree from the university of Toronto, where she wrote her thesis on human rights, women and health. About a week before she left Homemaker’s, Chatelaine named her editor-at-large, and she took her brand of international women’s coverage to Anderson’s old publication.

But tragedy soon occurred in her own life, when her husband, Ross, a businessman whom she credits with supporting her career, died in a car accident in January 2000. Her close family grew even closer (she has three adult children: Heather, Peter and Anna), and Heather moved in with her for a while.

Today, Armstrong balances family time with a hectic schedule of speaking three to four times a week and promoting her recently published U.S. edition of Ascent of Women. Last fall, she flew home after visiting a book club in Sussex, new Brunswick, to take her six-year-old granddaughter Julia trick-or-treating. Every summer, the whole family spends time at her northern new Brunswick cottage. “We party together very well,” she says. “We’re storytellers.”

Her long career is marked by some of the most significant stories in Canadian women’s magazines. At Homemaker’s, standouts included pieces on international relief to Somalia and a story about two teenage prostitutes, one a 15-year-old from Toronto and the other a 13-year-old from Bangladesh. For Chatelaine, she looked at the polygamist community in Bountiful, B.C., and explored one family’s grief over losing a daughter to serial killer Robert Pickton. She turned her years of reporting on women in Afghanistan into the 2002 book Veiled Threat: The Hidden Power of the Women of Afghanistan and followed up with 2008’s Bitter Roots, Tender Shoots: The Uncertain Fate of Afghanistan’s Women. She also wrote a novel based on the true story of a distant female relative: 2007’s The Nine Lives of Charlotte Taylor.

This CV has been built on two important traits: her extensive contacts around the world and her tireless willingness to fight for every piece. She wrote “Eva: Witness for Women” about Eva Penavic, 48, one of thousands of females aged eight to 80 who were brutally gang-raped during the conflict in the former Yugoslavia. The Summer 1993 Homemaker’s story powerfully captured Penavic’s fear: “When they shot the hinges off the door of the tiny stone cell where she was imprisoned, she knew she was about to look evil in the face. What she didn’t know was the diabolical shape it would take.” Armstrong got at the heart of the issue by writing that Penavic was “a woman who knows well that her gender doesn’t carry a safe-passage card.” Armstrong shows the human side of conflict by putting a face to women’s issues in many of her stories.

The story about the story is pretty powerful too: she heard rumours from women about rape camps while in Sarajevo in 1992. She wanted to get the story out faster than her magazine deadline would allow. She flew home and passed the information to a news editor. He ignored it. About seven weeks later, after a small blurb appeared in Newsweek about gang rape in the Balkans, Armstrong and her team at Homemaker’s decided to do the story themselves. Armstrong told Penavic’s story in a way that respected her humanity.

Her February 2013 CBC Radio documentary, A Remarkable Encounter, almost didn’t happen either. She pitched the story to Ideas producer and host Paul Kennedy at one of their “liquid lunches” at Il Fornello in downtown Toronto. When he said bud- get cuts meant they wouldn’t be able to work together that year, Armstrong told him about Alaina Podmorow, a teenager from B.C. who started her own charity to help Afghan girls get an education. “It was such a compelling case, of such obvious and overwhelming journalistic significance, that I asked my boss to make a special plea for extraordinary funding,” writes Kennedy in an email. “We would have been foolish and irresponsible to do anything else.”

Another classic Sally backstory: once, while in Afghanistan for Maclean’s, her computer crashed, and no one could fix it. She wrote a 4,000-word feature by hand on the plane ride home. “You do what you have to do,” she says. But sometimes her stories about the story reveal what’s truly challenging about her brand of journalism. In Somalia, in 1993, a horde of men attacked a truck in front of Armstrong’s van but left her party alone. She was detained in a Taliban desert compound in January 2001 from the late afternoon until noon the following day. She admits that was one of the many times she has been afraid. (She briefly considered writing about her experience, but quickly decided it was smarter to keep quiet.) “They are very difficult places to work in, but that pales in comparison to the size of the story you get,” she says of her international reporting. “And frankly, the privilege you feel for being there, to be an eyewitness to something that your reader might want to know about.”

Armstrong keeps fighting when she’s back home, while her story is going through the editorial process. When Chatelaine copy editors used the word “Afghani” in one of her stories, Armstrong “hit the roof,” according to former managing editor Caroline Connell, and explained that the “Afghani” is the currency of Afghanistan. She said that the proper term for people from Afghanistan is “Afghan.” Armstrong didn’t care what the dictionary said. She had been there and knew the correct term. She won.

***

“Sally’s got a huge following. People love her,” says indie bookstore owner Ben McNally. But before Sally was Sally Armstrong, a “pioneer of international women’s stories,” to use a phrase from The Globe and Mail’s editor-in-chief John Stackhouse, there was skepticism. “I didn’t recognize Sally as a sister journalist until some time had passed and she had proven that she had the chops,” says Landsberg. Toronto Star columnist Catherine Porter, born in 1972, was among feminists who were against magazines that encouraged domesticity, but Armstrong’s work convinced her otherwise. “Sally showed that you could be interested in cooking and in the Taliban.”

CBC’s Anna Maria Tremonti also thinks Armstrong created an admirable model at Homemaker’s: “You don’t have to do light- weight journalism if that’s not what you want to do.” Ascent of Women is the opposite of lightweight. The book’s tone is confident, with Armstrong’s trademark writing style that combines simple yet powerful prose with more flowery descriptions. The first line: “The earth is shifting. A new age is dawning.” Later, she writes about the West Bank: “Grapefruit trees were laden with fruit, and songbirds were feeding from the nut-bearing bushes as the sun was starting to set.”

Although her writing today may be bold, when Armstrong started at Homemaker’s she didn’t even have enough confidence to ask the art director what basic layout terms meant. But she’s always had passion, which is still her biggest strength as a journalist. “She’s always been ahead of the crowd of journalists in both taking on issues and going to places that many others did not dare to go,” says Stackhouse. Photographer Peter Bregg says she cares deeply about every aspect of her work—the people she writes about, the surrounding issues and the story itself.

Armstrong has never taken a reporter’s just-the-facts approach—she gets at emotions. “She had a real sense of narrative and character,” says Connell. “As a prose stylist, she wasn’t the most polished. There are other writers I can think of who sweat every word.” But Armstrong’s voice added something unique to the magazine. Former Chatelaine staffer Beth Hitchcock agrees: “She was all in. She wanted to get to the very heart of the people she was writing about.” Sometimes Hitchcock would ask Armstrong to step back from her subject to ensure objectivity. Her 1992 biography of Mila Mulroney was widely slammed for being too fawning.

Hitchcock says Armstrong’s “level of compassion and enthusiasm” for her stories was always unmatched. Despite that, she hasn’t won every battle. In January 2001, she sat in the basement of an Afghanistan rehab centre while a group of women talked. They’d told her stories before, about the Taliban’s hatred of the sound of high heels and about windows painted black. Now they spoke of a man who lived in a mansion and who wanted to change their religion and culture. They took her to see a marble-pillared, two-storey estate with a vibrant green lawn—despite a drought—and explained his name was Osama bin Laden, and that he worked in a cave 30 kilometres north of Kandahar. But her Chatelaine editor said nobody would care and removed the paragraph about bin Laden from the May 2001 story, “Shrouded in Secrecy.”

***

Armstrong’s midtown-Toronto condo, which she moved into four years ago after selling her suburban home, is furnished in beige and dusty rose. She keeps copies ofHomemaker’s inside a cabinet in her elegant office. “We did some good work,” she says of the magazine that ceased publication in 2011.

That good work continues—and there’s almost too much of it. Armstrong admits that her schedule of speaking, reporting and writing is exhausting, but it’s nothing a few days of rest can’t fix. The former gym teacher still lives an active lifestyle; she went hiking in the French Alps with three childhood friends last September. She wishes she had more time to read and exercise, but her work trips by the end of this year will include Africa, Afghanistan and Western Canada. She still has stories to write.

Women’s struggles around the world get more attention now. In Canada, at least, Armstrong has had something to do with that. Meanwhile, the lives of many women are changing for the better. The 160 child rape victims in Kenya won their case, and a group called Young Women for Change in Afghanistan is using Facebook in an attempt to improve the way men treat women in that country.

Today, stories on international women’s issues are few and far between in Canadian women’s magazines. And Armstrong hasn’t written for Chatelaine since 2011. She’s found other places to write—but that’s another story.

About the author

Aya Tsintziras was the Online Handling Editor for the Spring 2014 issue of Ryerson Review of Journalism.

Hello! Forgive me if this is the wrong venue to leave a note for Miss Sally Armstrong but I was fortunate enough to be the last photo in her article on women in the Gulf —Ableseaman Sylvia Glavin—I just wanted to thank her for her amazing work and career. I always wonder what has happened to all the Gulf War Vets and am doing my best to investigate. I have made some great discoveries thanks to youtube (a great American conference featuring women of the military which credits the Gulf War to opening up the roles for women in the US military) and I joined a Gulf War Vets site but haven’t seen any girls in it yet of the 256 or so in a closed Facebook group. The guys are very nice! I also spoke at a US Presidential Sub-committee investigatory group once in Ottawa (I was the Naval “non-officer” presenter there was a combat arms gal and a female fighter pilot for the other two element, army and navy)

Anyway I always thought it would make an interesting story to find the gals in the article and see how their career and lives progressed after the Gulf experience…our first ever girls on the front lines.