The Breakout – August 2008

The opening was small but it would do.

Danny knelt on the cement floor and peers out to get his bearings. He could see a narrow ledge running just outside the hole and the interior prison yard down below. He looked behind him, along the corridor toward the guard station. All was quiet. A half-dozen inmates crowded round in anticipation, waiting for Danny to decide. He tied his long, black hair into a bun on the top of his head and took a deep breath.

“I’m gonna go,” he said.

Excerpt from The Ballad of Danny Wolfe: Life of a Modern Outlaw. Printed with permission from Penguin Random House Canada

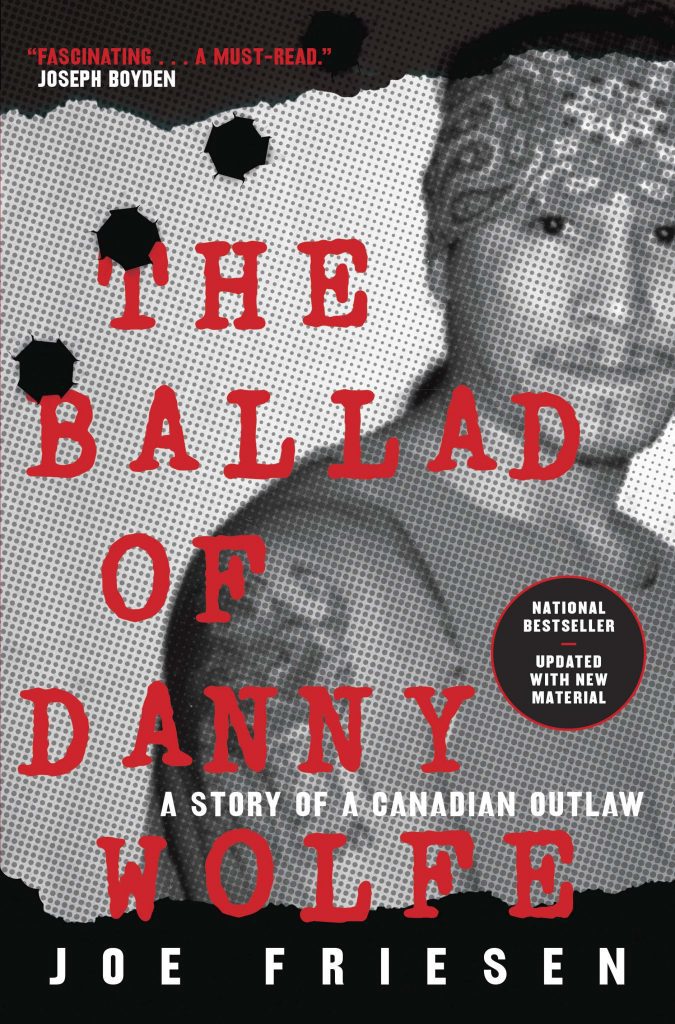

Joe Friesen’s non-fiction book, The Ballad of Danny Wolfe: Life of a Modern Outlaw, begins like a crime novel—meticulously detailed and tensely written. Although you may never have heard of Danny Wolfe, he started one of the most dangerous gangs in North America, the Indian Posse, when he was 12. Along with his 13-year-old brother, Richard, he inflicted mayhem and murder on the streets of Winnipeg and beyond. In a fast-paced, gripping style, Friesen takes readers through Danny’s life, starting in Regina, where he was born premature. It’s easy to see Danny as a big-hearted underdog: He started stealing food and clothes off laundry lines in the neighbourhood as a small boy just to survive. While the original intent of his gang was about sharing and belonging to a new type of family, it ended up being about selling drugs, committing murder, and dying violently in prison. Friesen takes it beyond crime to another level by addressing themes of domestic violence and addiction—fallout from residential school abuses suffered by Danny’s parents.

With his book, Friesen has captured an important, volatile moment in Manitoba’s history. Karen McCall talked to him about the journalistic tools and techniques he used over the four years it took to write it.

Karen McCall: You got in touch with Danny and he agreed to talk to you, but after he was killed in prison in what made you hopeful you could still write that original feature that started the book?

Joe Friesen: For a while I didn’t think I could tell the story. Then I got in touch with Danny’s brother Richard. The first time I was supposed to meet with him in Saskatchewan, he stood me up after I travelled all the way out there at a time when newspaper budgets were shrinking. He was too afraid to talk. I had never gone anywhere before and come home without getting the story. I felt terrible and didn’t think the paper would give it another shot. But my editor said to give it time. In four months, Richard got back in touch, [saying] that he would like to speak to me for real. I flew out again and he gave me several in-depth interviews, and then his mother came to meet with me.

McCall: How did you get so many of the characters, from hardcore gang members to Danny’s mother, who’s recovering from addiction, to trust you?

Friesen: As a reporter I try to present myself as honestly and straightforward as possible, and I listen. Sometimes that’s the best journalistic approach, just to say, ‘I’d like to hear your story. I know this must be difficult.’ I used different approaches for different types of people. Danny’s mother was a little skeptical at first. She went to pray about it, and the elders told her that this book would be a good idea and would help people understand her sons and the world in which they grew up. I approached it in a culturally sensitive way. When I went to talk to her, I brought her tobacco. I told her a bit of my understanding of the story, and that there would be difficult moments. Then I went away and gave her time.

McCall: How did you build the character of Danny?

Friesen: It’s very true to the truth. It’s a gritty story and it was dark story. What I wanted to do was make Danny come alive as a three-dimensional human being who had strengths, weaknesses and faults, but he wasn’t a simple character that you see portrayed in a news story. In a book, you have the length and the depth to explore other aspects of his life. I talked about how Danny wished he could be a better father, his own struggles with his past, and his parents’ past. With access to his letters, I was able to get inside his head to a certain extent that I didn’t think I would be able to.

McCall: This book has a tremendous amount of detail, with a plot that reads like fiction. What kind of resources did you use in your research?

Friesen: I was given a huge amount of Danny’s letters—about 40,000 words. As I read through all of those, I typed them out so I could have them as a searchable database. I knew looking at them they were a rich resource, but it was like looking at a puzzle broken into a million pieces. I didn’t know who he was referring to and I couldn’t put it together. I knew the beginning and the end but not the middle, and it took years of doing the background reporting on the other figures, and the gang before I started to piece together what was going on the letter conversations. I also had Danny’s prison records, which his mother supplied, and about 1,200 pages of documents.

McCall: As you got further into writing the story, did you ever feel nervous interviewing members of the Indian Posse, Manitoba Warriors and Hells Angels?

Friesen: You have to be fairly careful when talking to these guys, but they weren’t looking for trouble when they were talking to me. I did my best in a similar approach that I used when talking to the family—it’s not as exciting as it might sound. It really is like meeting someone for a coffee. Very often speaking on the phone or writing to them in prison then getting a phone call from them later on. That was my typical research method.

McCall: How did you find the balance between reporting and building an exciting narrative?

Friesen: I wanted to keep the story as close to Danny as possible so the reader would feel close to him and understand where he grew up, and the situations he faced when he made the decisions he did in life. When the story wanders away from Danny, it’s when I fill in context of the gang, his family, life in Manitoba in the 90s, the riots at Saskatchewan Penitentiary, and the growth of the Manitoba Warriors. I wanted to keep the story moving quickly so it had a plot and drama that would draw the reader in and so readers would learn a few things.

McCall: The book starts with one of the biggest prison escapes in Canada, which is suspenseful, exciting reading. How did you recreate that scene?

Friesen: There was a public report done on the prison break, which is a great place to start… I also did a freedom of information request to get all the government communications about that prison break, which gave me more information that was not available to the public. Then I had a couple of sources that could tell me what happened. I interviewed them at length because they took part [in the prison break] and went back several times with questions to try and get the details. There are little details that were so hard to explain and describe, like the tools they created [and used in the escape]. I’m still not entirely happy with the way I described that portion of it. The way they found the material to make the tools and how they used the tools was complicated and not easy to put into words, so I had to do a lot interviewing back and forth with the people who took part.

McCall: What was the most important piece of research and how did you obtain it?

Friesen: The personal letters were an enormous get. Danny’s brother Richard gave the letters to me willingly. It was around 5 p.m., everything was closing, and I was leaving on a flight out of Regina in few hours, but Richard didn’t want to let me have the originals. He said, ‘You have to do this now or come back at another time’. I knew there was a chance that I would never see those letters again, so I had to do it while he was there with me. I went to the information counter at a mall asking if there was anywhere I could go to photocopy, like a Kinkos or something. Apparently they had never heard of Kinkos in Saskatchewan, because the women went away and conferred with her boss who came back, looked at me sternly and said, ‘So you’re looking for a sex shop?’ and I said, ‘No, no, I just need to photocopy some documents.’ We finally found a copy shop that was open late and I was able to photocopy the letters and catch my plane.

Friesen, who is a Ryerson Journalism School alumnus, has five tips for students focusing on longform features:

- Follow up on little news items or the stories that nag at you, because there is often a bigger story to be done. This one flashed through the headlines after Danny’s escape from prison. I had never heard of Danny Wolfe, but I sure wanted to know more about him. It wasn’t easy because he was in jail at the time and wasn’t keen to talk, but I convinced him to talk to me. Over the years, doors that were closed eventually opened.

- Look for the official documents. Go to the courts. There is so much in there that doesn’t get used in a daily news story.

- Time is always an important ingredient in reporting that people don’t always realize at the beginning of their careers. They think if they can’t get something in a day or two days, they’re never going to get it. But come back to it, be persistent, and your odds improve significantly over time.

- When you take on a long project, you think it’s going to be impossible. This book ended up being 100,000 words, but I made them write into my contract that it only had to be 50,000 because I didn’t think I could write that many words. But you’ll find the material is there. Don’t worry about length; just find a good story.

- There are a ton of great stories around in Canada that aren’t being told. The hardest part of journalism is choosing and framing a story (understanding what it is you are really going after). It’s the question you are seeking to answer and the parameters of the story. It takes practice and doesn’t come easily. I think I was at the Globe for a year and a half before I learned how to choose and frame a good story. I try to do a simple outline first in point form with 10 to 12 points. I’m not a great planner or plotter, but I do the minimum amount, which is to say, the things I’m going to hit on. Often, what I think at the beginning is not where I end up but it gives a beginning.

If you missed this national best-seller when it was published last year, the paperback edition is being released Tuesday, April 25.