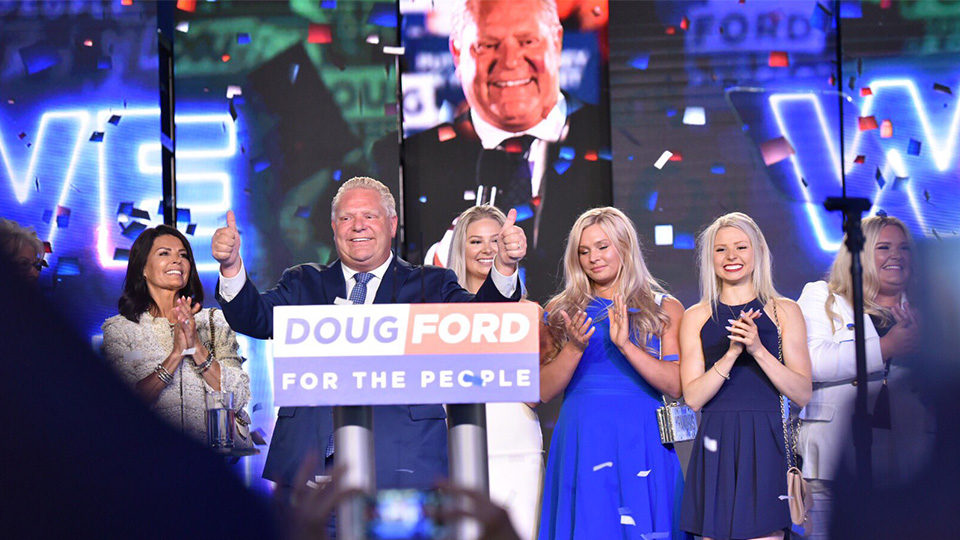

On June 29, 2018, Doug Ford was sworn in as the 26th premier of Ontario following 15 years of Conservative opposition. Since then, the PCs have executed a flurry of headline-making changes to cap off six months in power, and while some developments received extensive press coverage, others received little to none. Here’s a look back at political issues in the news since Ford’s election—as well as what’s missing from the analysis.

To culminate his first 100 days, CBC published an article outlining the 10 most significant things Ford has done since taking office. Heading the list is the September cuts to Toronto’s city council, reducing the number of seats from 47 to 25. Next in line, is his decision to roll back Ontario’s 2015 sex education curriculum, replacing it with the 1998 version. Ford has also appointed a special committee to investigate the Liberal managing of the province’s finances, is scrapping the Green Energy Act and winding down cap-and-trade—one of his central campaign promises.

But despite journalists honing in on key issues since Ford’s election, emphasis on particular topics has led to neglect of others. This lack of analysis largely stems from media’s rapidly changing landscape, as well as shrinking newsrooms—over the past year, both Torstar and Postmedia announced job cuts. And according to the Public Policy Forum’s 2017 report “The Shattered Mirror: News, Democracy and Trust in the Digital Age,” these downward trends “risk the dismantling of traditional news outlets, which would imperil the health of Canadian democracy.”

As a result, some experts worry journalists are missing important stories, as well as failing to provide meaning in their reporting—too often focusing on back and forth debates between those in power, rather than providing crucial context. Consequently, this type of narrow coverage leaves the public only marginally informed about urgent political issues.

“There are a number of changes the new government is making that the public should be aware of… cap-and-trade, the sex-ed curriculum,” says Robert Benzie, Queen’s Park bureau chief for the Toronto Star, naming contentions that have made a splash over the past six months. He calls the cuts to Toronto City Council “close to one of the biggest [policy changes].”

Ontario’s electric power distributor Hydro One has also been making headlines. In December, news broke that U.S. regulators rejected Hydro One’s takeover of the American company Avista Corp., citing political interference by Ford. Hydro One later requested the Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission reconsider the order; however, the Commission denied the deal again on January 8. The quashed proposal could cost taxpayers tens of millions in cancellation fees, according to a Toronto Star article.

But for all the coverage some issues like Hydro One receive, there are equally as important issues that fly under the press—and therefore the public—radar.

The government’s cancelling of a project that would update the provincial curriculum to include Indigenous content hasn’t received equal coverage compared with the repealed sex education curriculum. In July, the PCs announced an already-scheduled re-writing session, which would revise the curriculum in response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC), would be halted.

Another issue that hasn’t garnered enough press is Ford’s axing of regional chair elections in Peel, Muskoka, York, and Niagara back in July 2018 says Benzie. The move was under the same legislation that shrunk the size of city council. In response to the cuts, Ford told reporters that too many politicians make it difficult for the government to get things done.

“There was little talk about the cancellation of four democratic elections in the middle of a campaign. As a Tory friend of mine said to me, ‘That’s what happens in Third World countries, Banana Republics.’ That’s not the norm.”

When asked why some political topics receive widespread attention and others don’t, Benzie addressed the amount of ground Queen’s Park reporters must cover—shrinking newsrooms mean journalists can’t do a deep dive into each issue.

“There are 23 ministries (in the provincial government,)” he says. “And there are only so many things reporters can write about… we have to make choices all the time.”

Besides Benzie, the Toronto Star Queen’s Park bureau also consists of Kristin Rushowy and Rob Ferguson, with Martin Regg Cohn as the regular columnist.

And though a story may receive coverage, it doesn’t always mean the coverage is sufficient. Carleton professor Paul Adams says journalists often use a standard structure to formulate news articles, one where the discussion is framed as an argument between two parties or two governments. The problem with this method is that it fails to adequately inform the public of fundamental issues. Adams uses the example of climate change and carbon tax to flesh out the idea.

“It’s easy for reporters to feel we’ve covered climate change, for example, because we cover the Ford government’s announcement, and then we cover the way the federal government reacted to it and then the minister’s conference where there’s an argument…” he says. “But the underlying issues around our future as human beings or the future of our planet, that isn’t adequately covered in these narrow political debates.”

This type of balanced reporting—giving near equal weight to both parties in dispute—fails to provide broader context and reflect on the relevance of the story at hand, leaving its audience confused about the facts.

Adams speaks to the firing of Ontario’s chief scientist Molly Shoichet as another example. Shoichet was appointed by the former Liberal government with the goal of advancing science and innovation in the province but was let go in July, shortly after Ford took office. Stories like this tend to focus on the immediate incident, but leave the public wondering what this means about the PCs attitude towards science, or what the consequences will be long-term, says Adams.

“In a sense, we overplay the event, which is the firing and then underplay what’s the true issue, which is what flows from the firing.”

News of Shoichet’s removal was lumped in with Ford’s simultaneous firing of Ontario’s chief investment officer and Ed Clark, the business advisor and privatization czar since 2015.

John Milloy, assistant professor at Martin Luther University College and a former Ontario Liberal cabinet minister, says there could have been more information on what Shoichet’s role was within the government, what policies that role connects to, and why she was removed from such a position.

“How can I blame journalists? I mean, they’re operating on shoestring budgets… But I think more and more you’re seeing very little context being provided by reporters.”

Milloy says the press has also been mostly silent on the PC’s cutting of three legislative officers, eliminating the Ontario child advocate, the French-Language services commissioner and the environmental commissioner.

Legislative officers, also known as parliamentary officers, oversee activities of government that are of particular concern and are considered independent watchdogs, holding those in power to account.

“Where’s the discussion about parliamentary officers and their role? … The government is essentially silencing what could be their critics going forward,” says Milloy. “That’s a perfect example where I think the press missed the boat… [people] don’t know what a parliamentary officer is, they don’t care, but they should care. And I think part of the media’s job is to explain to them why they should care.”

On December 6, a bill was passed to remove the environmental commissioner, Dianne Saxe, as an independent watchdog, 25 years after the position was created. The National Observer has been one of few outlets to cover this issue in depth, explaining in a January article that the bill passed three weeks after it was tabled, and only saw a few hours of public consultations.

So, how can journalists improve their coverage of the Ford government moving forward?

Benzie says it comes down to reporters staying focused and telling stories their readers care about—particularly ramping up coverage on climate change.

“I think that’s one of those sleeper issues we have to watch, and the government has to do a lot better… whether it’s the federal government or the provincial government [they] have to be a lot better at reducing [greenhouse gas] emissions, so that’s something [journalists] have to watch.”

Journalists must consistently go back and reconstruct issues from the bottom up, as well as resist being consumed by politicians’ partisan rhetoric, says Adams. He adds that reporters must also provide the public with further background on the issues at hand and what the consequences will be if those in power fail to address such problems, whether related to education, Indigenous issues, health care or climate change.

“As a legislative reporter, those aren’t always easy things to do because you’re down at [Queen’s Park] every day in the midst of the partisan debate, so you’ve got to pull your head out of it and think about these issues in a different way,” he says.

“That’s a challenge to us all.”