Jesse Brown sits in front of a microphone in a stuffy, low-ceilinged studio. Six people can squeeze into the room—which Brown calls a cross between a confession booth and interrogation chamber—but it’s still cramped with two. While Brown likes the cosiness and that it isn’t like CBC’s high tech “space pods,” his Canadaland team may be outgrowing the soundproof room with so many shows vying for recording time these days.

Although Brown’s media criticism remains the core of the podcast brand, Canadaland now has a second weekly episode called Short Cuts, a comment on media coverage in chat format; two politics podcasts called Commons and OPPO; and The Imposter, about Canadian arts and culture. The office is in a refurbished red brick building in downtown Toronto that leases subsidized space to artists and start-ups. Despite the air-conditioning unit wedged between the wood frames of the hundred-year-old windows, the room bakes in the July heat, and the studio off the main area is worse.

“So we know some stuff. Stuff about the Canadian media that we have not told you about,” Brown says on the episode, “Summer Dump,” and continues, “We’ve been sitting on this stuff, it is in our files, unreported, and it bugs me. Because like, what are we even doing here if we’re not telling you this stuff?”

Canadaland has built its audience by breaking stories, and pressure is high to churn out more. After announcing he’ll dump this “stuff” without any on-the-record sources or documentation, Brown introduces Jonathan Goldsbie, news editor since January 2017. Goldsbie is humble, candid, and perpetually jolly, with a more careful approach to publishing. “We have to aim to be better than the places we call out,” he says, “and better than the places we criticize.”

He runs the website, which draws over 160,000 page views per month, while Brown, the bigger personality, hosts the media criticism podcasts. Canadaland’s goal is to break the stories others are afraid to break, and it thrives on publishing “stuff” first. The podcast has largely been tethered to Brown’s opinions and observations, keeping the powerful in check—or at least looking over their shoulder—but finding the balance between gossip and news has been bumpy. Brown has received flak for getting carried away, and not always getting “stuff” right. And that’s held him back from really rattling the industry he loves to hate.

During high school in the mid-1990s, Brown’s underground magazine, Punch, ran a student poll that rated teachers. After the principal banned the magazine and threatened to expel Brown, they appeared separately on CBC Radio’s Metro Morning to argue their sides. Years later, Brown staged pranks for a humour column in the now-defunct Saturday Night magazine. Under the alias of Stuart Neihardt, he launched a fictional publication called Stu, a “regular guy magazine for the adequate man.” The hoax fooled many journalists, including the National Post’s Colby Cosh, who wrote a piece called, “Who’s afraid of lad mags?” Brown told Antonia Zerbisias, then the Toronto Star’s media columnist, “I hope to keep you people (in the media) on your toes.”

While working on Search Engine, a CBC radio show that ran between 2007 and 2008 that looked at the internet’s effect on everyday life, Brown clashed with CBC culture and was a bit of a misfit. “We didn’t try and fit in at that point,” says Geoff Siskind, who produced the show. “We were kind of on our own island making this weird thing.” At one point, Brown asked him what would be the most “punk rock” thing to do at CBC, which prompted Brown to begin wearing a well-tailored shirt and tie to the office, throwing the executives off guard.

Siskind says that’s just who Brown is, loudmouth and all: “He does things based on logic rather than tradition.” Years before CBC and Canadaland, the two became friends on a train from Montreal to Toronto. Brown sat next to Siskind since they knew of each other from high school: “My first thought was, ‘Oh, for fuck’s sakes, I have five hours with Jesse Brown.’” By the end of the journey, they were good friends. “He’s totally arrogant, but that’s his charm, and he works it well,” Siskind says with a laugh.

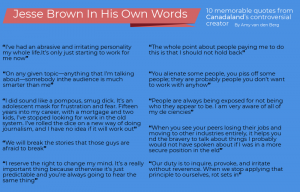

In 2013, at the age of 35, Brown launched Canadaland, working as a producer, host, and editor while he worked out the kinks of a project that cost more than it brought in. From the start, Brown deliberately avoided any Canadian niceness. “I’ve had an abrasive and irritating personality my whole life,” he told the Star. “It’s only just starting to work for me now.”

Brown had pitched a media criticism platform to CBC, Maclean’s, and others, but interest was low so he did it himself. In a 2014 Walrus article, he described Canadian media as “more of a club than an industry,” and blamed the timidity of journalists to speak out about each other on the closed atmosphere and centralization in Toronto, which he previously called “chummy and incestuous.” Both national newspapers are based there, as well as nearly 20 major magazines and the domestic offices of American sites such as BuzzFeed and Vice. “Once you’re inside the bubble you can’t really critique the bubble,” says Maija Saari, associate dean of the film, television and journalism department at Sheridan College in Toronto. “I think his success is just speaking to the testament that we needed this, we needed a place where people could go and be critical of the media.” While programs such as NPR’s On the Media in the United States, BBC’s Charlie Brooker’s Weekly Wipe and The Media Show in the United Kingdom, and Media Watch in Australia hold journalism to account, Brown has previously declared in J-Source that he is the only person in Canada doing media criticism in a notable way, and that he would welcome more. Although there is a shortage in the country, Canadaland isn’t alone. The Ryerson Review of Journalism, “Canada’s watchdog on the watchdogs,” has been analyzing the industry since 1984, and several magazines, including Toronto Life, The Walrus, and Maclean’s, occasionally do stories about journalism. At The Globe and Mail, Simon Houpt and Susan Krashinsky Robertson sometimes write on media, but most newspaper coverage has been reduced or cut altogether. There are also bloggers such as the Montreal Gazette’s Steve Faguy. “I think it’s like every other beat that is covered by journalists,” says Faguy. “It has suffered over the past 10 to 15 years as media has contracted and interest for specialized beats has disappeared.”

“Brown’s heart is in the right place: He wants to be a journalist, he wants to be a critic of the media and those are really great things,” says Donovan, “but he’s a bit of a bull in a china shop”

But it’s also a stressful topic—the Star’s Zerbisias felt so burnt out by the backlash that she left media criticism and switched to the culture and social justice beat. “When I was doing it, I was under constant attack,” she wrote in an email.

Canadaland’s first episode was little more than Brown and his old CBC boss and mentor Michael Enright drinking bourbon and discussing Canadian media. “Essentially just two old mates talking shit,” says former Canadaland freelancer Sean Craig. “With that first podcast, Jesse wanted there to be conversations out in public more like the ones those of us in the media have in bars, where we’re more cutting and honest and willing to be snide.”

Craig first met Brown at a Canadaland social in 2014: “I was immediately taken by the tongue-in-cheek combativeness that Jesse playfully articulated in those days, a philosophy of wanting to be a kind of tabloid insider-cum-pariah of the industry in the same way you imagined Nick Denton in the early Gawker days.”

Created by Denton in 2002, Gawker was a New York-based blog about celebrity gossip and media news with a tabloid mentality and clickbait headlines. Although the Star had the Rob Ford crack video, Gawker released it first. “Honesty is our only virtue,” was one of its slogans, along with “Today’s gossip is tomorrow’s news.” But it pushed privacy boundaries and violated copyright, ultimately leading to its 2016 demise when Hulk Hogan successfully sued Gawker over a leaked sex tape, and was awarded $115 million (U.S.).

Canadaland models itself on Gawker in some ways but not others. Brown struggled with outing people and crossing privacy lines, but found its self-critical, transparent style refreshing. He particularly admired the way the site valued the reader’s right to know, and he has strived for a similar level of transparency, saying, “You may not like us for telling you these things, okay hate us, but the information is good.”

And Brown has attracted his share of supporters. “Let’s face it, he’s a guy with a big personality and I think the people who like him like him a lot and the thing with him is you know exactly what you’re getting,” says Terra Tailleur, an online news and media specialist and instructor at the University of King’s College, in Halifax. Brown has spoken to her class and Tailleur says many of her students would rather support Canadaland than subscribe to the Globe: “We need Jesse and independents like him.”

Canadaland broke its first big story in February 2014, when it reported that Peter Mansbridge had accepted $28,000 to speak at an oil sands lobby group, despite covering the industry on The National. Mansbridge responded in a CBC blog post, saying, “I follow the rules and the policies the CBC has instituted,” and upon investigation ombudsman Esther Enkin found no formal issue with the event, yet CBC eventually changed its policies surrounding speaking engagements. Eight months later, Brown and Star investigative reporter Kevin Donovan broke the story of sexual assault allegations against popular CBC Radio host Jian Ghomeshi.

Coincidentally, Brown had just started a crowdfunding campaign. The website has yet to eclipse the buzz reached at the height of the Ghomeshi trial, but Canadaland soon reported that Amanda Lang, then CBC’s senior business correspondent, had allegedly given Manulife and Sun Life Financial favourable coverage while failing to disclose that they had paid her between $10,000 to $15,000 per speaking engagement. One month later, Canadaland released two more stories on Lang, producing evidence that she had interfered with the broadcaster’s coverage of the Royal Bank of Canada during its temporary workers program scandal, while having done paid speaking engagements for the bank and not disclosing she was in a relationship with a member of the board at the time. CBC News editor-in-chief Jennifer McGuire defended her in a memo to staff, saying the allegations were “categorically untrue,” and in an article published in the Globe, Lang stated that she never violated CBC policy and supported the company’s new decision to ban paid speaking engagements for on-air staff. The day after publishing the first Lang story, Craig walked into the Canadaland office after she had tweeted, “The haters hate,” and he says it felt like victory. Neither he nor Brown said a word; they just shook hands. “Getting someone mad on the internet was cause for momentary joy,” says Craig. “That sense of priorities speaks to the early-days Gawker DNA that we had in us.”

But the Ghomeshi story exposed the limitations of being an outsider. Brown needed a legal team to defend a likely libel suit. Fortunately, the Star needed his sources. But Brown and Donovan butted heads on how to do the story, and the relationship grew increasingly volatile. In Secret Life, Donovan’s book about the investigation, he remembers getting to know Brown as they talked about their kids in the car ride to their first joint interview. But the Star reporter soon grew frustrated. “He was not as objective as I would have liked him to be,” says Donovan. “He thought that the journalist should be in partnership with the victim and that’s just not right.” Donovan put it down to a lack of experience and was concerned about Brown’s desire to get a big story out even as the Star and Donovan were unwilling to publish without more women and some confirmation of the events: “No journalist should ever want to risk being wrong by moving too quickly.”

Late one night at the Star office, while Donovan and Brown worked on the second Ghomeshi story, Brown tweeted a picture of the back of Donovan’s chair, saying the two were burning the midnight oil. Donovan was not happy. He worried that Brown had jeopardized a serious and confidential investigation. “Brown’s heart is in the right place: He wants to be a journalist, he wants to be a critic of media and those are really great things,” says Donovan, “but he’s a bit of a bull in a china shop.”

Brown’s outsized personality, growing ego, and eagerness to share information makes him a big target for critics. In a searing 2015 piece, the Globe’s Simon Houpt challenged the emerging Jesse Brown fan club. Writing Canadaland was “playing fast and loose with facts,” Houpt dug into a list of missteps, including the exposé on Lang, arguing that there was no evidence that Lang had corrupted the story and Brown had left out important information. Houpt hit a nerve when he accused Brown of cutting ethical corners in 2006 while working on the pilot episode of CBC Radio’s Contrarians, a program that debated controversial social questions. By the next Thursday, Houpt and Brown found themselves in the Canadaland studio, recording one of the most uncomfortable episodes yet. “It’s interesting that we’re discussing [laughs] what we publish and what we don’t publish in the name of ethics,” scoffed Houpt. “I’m sorry you were not aware of these guidelines that obviously, I guess, the mainstream media operates under.” The Short Cuts episode was titled “Two Annoying Jerks.”

Six months later, Brown received heavy blowback over a story headlined: “Women editors are fleeing The Globe and Mail.” He reported that a large number of female editors had quit within a three-year time period, suggesting a larger gender diversity problem within the newsroom. The article claimed the last four women to leave the paper hadn’t replied to requests for comment, but Brown admitted he didn’t try hard enough to contact them. And rather than fleeing, many had left for better jobs. Scaachi Koul, an author and BuzzFeed journalist, reprimanded Brown in a characteristically aggressive and public way—she often writes in capital letters and has 29,000 followers on Twitter.

When Brown invited Koul on his show, she didn’t hold back: “That is the most embarrassing thing you’ve ever done for Canadaland,” she said as she scolded him for the flimsy headline, the photograph—a Globe clipping of a figure skater with her leg in the air—the reporting and the execution. “It was bad, Jesse. It was extremely destructive.”

“So tell me why,” Brown said.

Mistakes in coverage of sensitive topics like race, gender, and politics have more weight. Men did dominate the top of the Globe’s masthead, but Brown made himself the story instead. The next time somebody reports a problem in a newsroom, Koul argued, nobody will believe it because Canadaland got it wrong the first time. “That’s why it’s a problem.”

In 2016, Huffington Post Canada’s Jesse Ferreras called Brown “a mistake-prone media critic who is perilously short on self-reflection,” and said that “someone who considers himself the conscience of Canadian media needs to do better if he wants to be taken seriously.”

Eight white Ikea desks are squashed together along the length of the office like a long dinner table. Books, coffee mugs, notepads, and Apple computer chargers are scattered about. Large blue and yellow CANADALAND letters sit in a disjointed stack by the windows—leftovers from a 2013-14 YouTube interview series.

Going from a one-man show to a team of eight people has been an adjustment. Brown has stepped back and given his staff more autonomy and Canadaland is slowly moving away from being The Jesse Brown Show. Commons began as a podcast for politically engaged young people. It was to be inclusive, honest, and nothing at all like CBC but, after a few months, hosts Desmond Cole and Andray Domise left for other jobs. Their replacement, Supriya Dwivedi, focused on the inner workings of Canadian politics while the current hosts, Hadiya Roderique and Ryan McMahon, are more interested in how politics affect people’s daily lives. Meanwhile, McMahon is working on a new S-Town-style series investigating the suspicious events surrounding deaths of Indigenous youth in Thunder Bay, Ontario.

Launched in 2016, The Imposter has evolved at a slower pace. Host Aliya Pabani focuses more on the process and culture behind the art world rather than the work itself (although that’s covered, too). These days the show also covers bigger stories and ideas to do with music, movies, comedy, and other “weird art.”

Finding a rhythm has taken a toll on staff. In just over a week in October 2016, Brown lost almost half of his team. First, Dwivedi took another job, then web editor Jane Lytvynenko and Commons co-host Vicky Mochama departed. At the beginning of the annual crowdfunding push, Brown recorded an episode called, “Guys, we’re having some problems.” His voice wavering, he said, “I have to tell you, I did not see any of this coming, and my head is spinning.”

Brown admits to having a “bootstrap” mentality: “Everyone here is going to have to work really hard but everyone will be included in the success.” Katie Jensen produced 139 Canadaland episodes and co-created The Imposter. “It was a stressful, hard place to work,” she says. But Brown says he understands the pressure, and acknowledges that people do better work if they can go home and disconnect. He has made moves to retain staff, including increasing benefits, introducing stocks, and raising pay.

The chatter at Mascot Brewery lowers to a hush as Brown raises his arms to the crowd. A gaggle of strangers and fans are slowly getting tipsy on a beer called Canadaland Sour. With a half-empty schooner in his right hand, Brown talks with his left: “Welcome to our sour beer launch and the end of our crowdfunding months.”

The limited edition beer’s logo is a lemon being squeezed into an ear, an insinuation that Canadaland tells the truth even if you don’t want to hear it. Brown describes it as refreshing—the kind of thing that you didn’t even realize you needed until it’s inside your head, and then you can’t get enough of it.

In October 2014, four months after his Walrus article, Brown announced that Canadaland was at “a crossroads,” and needed patron support to continue. He launched his crowdfunding campaign, promising that if 10,000 listeners contributed $1, the podcast and website could become larger, better, and sustainably independent. “I wanted a revenue model,” he says. “I wanted to run a business, and I wanted to be able to have some predictability to when I can make a mortgage payment or when I can hire people and address this larger question of how are we going to pay for journalism.”

He reached his financial goal within six months and went to work hiring staff, including an editor to oversee news coverage. On May 5, 2015, Canadaland launched Commons and promised new additions for each financial milestone, including increases to pay and benefits for each member of his staff (excluding himself ). A year later, after hitting $12,500 a month, it added The Imposter, and today Canadaland has 18 sponsors, and monthly Patreon contributions are just under $22,000 (U.S.). Crowdfunding has increased almost 80 percent in two years, and the sour beer is the latest way to draw more supporters. Patrons receive paraphernalia such as a copy of the network’s own satirical book, The Canadaland Guide to Canada, a bottle opener, socks, a T-shirt or, for $2 (U.S.), the Canadaland colouring book.

When Brown invited Scaachi Koul on his show, she didn’t hold back: “That is the most embarrassing thing you’ve ever done for Canadaland”

This has allowed Brown to keep the content free. “I’ve had some patrons say if you ever put any Canadaland shows behind a paywall I will stop giving you money,” he says. The average monthly donation is $4.92 (U.S.). “I’ve come to regard it as a really evolved form of capitalism,” he says. ”I no longer feel like I’m out there with my hat in my hand.”

Brown is a co-founder of cartooning app Bitstrips, makers of Bitmoji. Snapchat bought the app for $64.2 million (U.S.) in 2016, though Brown says he hasn’t invested any of the funds into his company. “I was adamant that Canadaland would not be my vanity project,” he says. “We’re doing this for real and we want to be here for a long time.” Staying around will require more big stories to keep people listening. “Back in the day, two years ago, sure we were always listening to him during the time after Ghomeshi because he would often bring up the Star,” says Donovan. “I have not heard anybody say to me in the past year, ‘Hey, did you hear Jesse Brown’s podcast?’” This is not uncommon. Many media critics and academics refused to comment for this feature, some saying they haven’t been keeping up with Canadaland’s podcasts or didn’t listen to them on a regular basis. Faguy compares some episodes to an investigative TV program that plays ominous music while a voice recites facts that aren’t all that controversial. He sees Canadaland as a tipster, digging up the dirt for others to scrutinize.

Following the controversy over the women at the Globe story, and Lytvynenko’s departure (she is now a reporter at BuzzFeed), Brown needed someone to help him refocus the original mandate. In December 2016, Goldsbie had a beer with Brown. He’d spent four years as a sta news writer at Now, a Toronto alt-weekly, and was looking for a job with more room for growth, and Brown was looking for someone who was detail-oriented and cautious. “It was de nitely the beginning of a new phase of the company,” Goldsbie says in an interview in October. “It doesn’t feel like it’s about to fall apart right now. I can imagine at this time last year it probably did feel that way.”

One thing that came out of that beer was a mutual agreement on boundaries. “Our arrangement is that I will never force him to publish,” Brown says. “If he’s not comfortable publishing it, he’s not going to publish it.” They both describe the clear tension between them as complementary.

During the recording of the “Summer Dump” episode, Brown announces: “the responsibility for the following content rests on my shoulders, not Jonathan Goldsbie’s.” The first story is about Toronto’s so-called “Lactate-Gate” scandal. Globe columnist Leah McLaren wrote about her attempt to breastfeed MP Michael Chong’s baby at a party many years earlier, even though she wasn’t lactating. The piece was later said to have been accidentally published, and was taken down hours after surfacing, while McLaren was suspended from the Globe for a week. Brown explains that the Globe editorial staff received the blame for the column, which he says sparked so much internal frustration that 72 newsroom staffers signed a letter of complaint to management. Brown also says McLaren barely touched the baby before being caught, despite her writing that she had picked him up. “I cannot reveal how I know this information but that is actually what happened.” Next, he exposes what people are saying about previously unknown political pressures that forced former Ottawa Citizen editor-in-chief Andrew Potter to step down from his new position at McGill after a controversial column in Maclean’s that offended many Québécois. In the piece, Potter used the events of a snow storm as a case study to talk about “social malaise” in Quebec, describing the province as a “pathologically alienated and low-trust society.” Potter later apologized in a Facebook post. Brown says evidence suggests that the fallout from the article may have caused him to be pushed out of his position by his superiors at the school, although he remained on contract as a professor. “We do not know whether this pressure did or did not exist but we can confidently say, ‘This is why people think it did.’”

While not as shocking as promised, this “stuff” is to his chest and, for the moment, his job is done. As Brown says, “I hate sitting on a story when I know it’s true.” That cavalier attitude is a hangover from Canadaland’s dishing-over-drinks beginnings, but it’s something he’ll have to leave behind if he seriously wants to shake up Canadian journalism.