At age 12, Julie Scott was the only girl in a boys’ hockey team. There were no girls’ teams when she was growing up in the 1980s in Guelph, Ontario, but she was determined to play hockey just like her big brother. Buried under padding and sometimes using her brother’s old equipment, she proved she was just as good as the boys. Now, almost 30 years later, the head of the sports section at Canadian Press applies the same determination to a male-dominated industry.

Many women in sports journalism acknowledge the skewed gender balance and sexism in the industry but would rather not dwell on these negative aspects. Instead, some female leaders are supporting each other and mentoring the next generation.

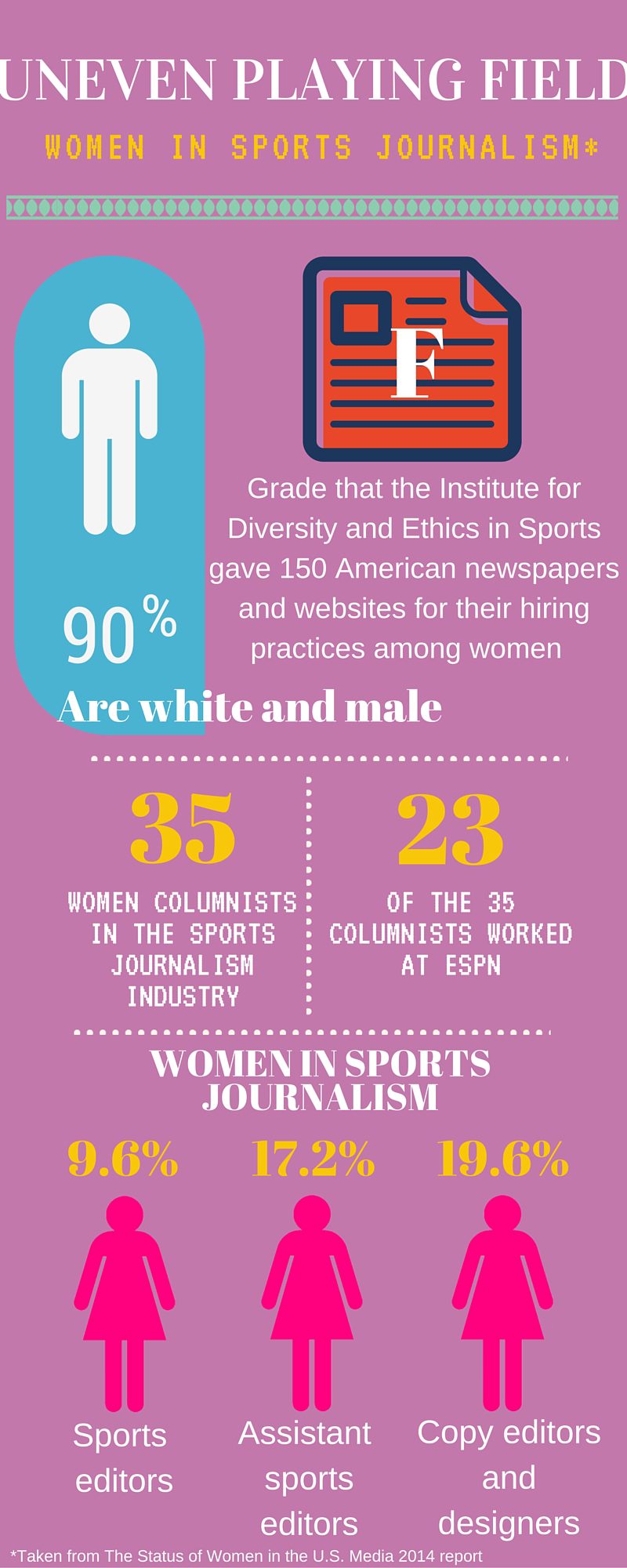

There has always been a huge gender gap in sports journalism. According to a 2014 U.S. study by the Women’s Media Center, women make up less than 10 percent of journalists in this beat in print and online. This ratio extends beyond the borders of the U.S. and many sports desks continue to be notoriously unbalanced.

Early in Megan Robinson’s career, a much older male superior told her that she would never make it because she talks like a girl. That was a decade ago, but she still thinks about it from time to time. Today, the Global sports anchor runs a series called Women at Work on her blog that highlights women in various industries. She wants to give them a platform to discuss challenges they face across all fields, and to unite them through storytelling. Robinson says there were many times when she experienced sexism at work at some of her past jobs. She’s been doubted by male colleagues and catcalled in locker rooms. In one post, she links a CBC video of sports reporters speaking out against sexism. The women in the video discuss experiences they’ve had on the job and why they feel like they can’t talk about it. One says, “If you said something, you’d probably be perceived as being weak.”

But things are finally starting to change: at four leading Canadian news organizations, women hold some of the highest positions in the sports sections. Scott is the senior editor of the sports-arts-lifestyles section at CP, Jennifer Quinn is the sports editor at the Toronto Star, Shawna Richer is the sports editor at The Globe and Mail and Bev Wake is the senior executive sports producer at Postmedia Network in Vancouver.

These women made it to the top in an industry that is historically overwhelmingly male despite the pitfalls and ingrained sexism that accompany the job. Although there is competition between their news organizations, the women are friends. They meet often—usually when Wake is in Toronto—to have dinner, catch up and encourage each other. “We’re a good support system for each other,” says Scott.

While it’s refreshing to see women at the top in sports journalism, Jan Kainer, a professor at York University in gender, sexuality and women’s studies, says it’s an anomaly for many professions. The majority of women aren’t given leadership opportunities. Kainer’s course on women in professions analyzes the way women need to act like men and sound like men in order to be accepted. The way female sports broadcasters speak is distinctly masculine, while their appearances are exaggeratedly feminine. “It’s such a contradiction,” says Kainer. This is why comments such as “you talk like a girl” can be damaging.

Subtly sexist language can be the most harmful. Robinson is always referred to as a “female sports journalist,” while male colleagues are just sports journalists. “It’s a subtle way of sorting or reducing,” says Rachelle Williams, a freelance writer and intersectional feminist advocate in Toronto. “The problem is that this can delegitimize the work a woman in a field is producing, and make her sex or gender identification more prominent than the actual work she’s producing.” She says this practice of modifying titles can be seen in other typically male-dominated industries, such as engineering, and can also be applied to people of colour and those with diverse sexual orientations.

Scott and Quinn know they’re lucky to work in progressive newsrooms and want to mentor and support other women in the industry. Along with other colleagues, they run Women in Sports Toronto, a networking and mentoring community inspired by their friendship. “We recognize that we’re quite lucky to have each other and it’s good to share that with other members of our community,” says Quinn. Events so far include a panel discussion at Ryerson University and a time for members of the industry—mainly women—to socialize and talk about jobs, applications and story ideas.

At Women in Sports, the focus is on mentoring. Terry Taylor from Associated Press and Jane O’Hara from the Ottawa Sun were pioneers of female sports journalism and women that Scott looked up to and admired. Now, she is able to do the same for others, which she considers the most rewarding part of her job.

Meanwhile, Robinson uses the negative aspects of the job as motivation. “No matter what,” she writes in an email, “I have chosen and continue to choose this field every day because I love it and because the stories matter to me.”

About the author

Sydney Hamilton is Head of Research on the Spring 2016 issue of the Ryerson Review of Journalism

I really don’t think you’ve made the case you intended to make.

The best you can come up with as proof of “sexism” is one reporter’s memory of a time long gone. You insist that “[w]omen are vastly underrepresented in sports journalism” but have not bothered to document any research on female journalists’ *desire* to work in sports journalism. What if the number of women in sports journalism accurately represents the proportion who actually want to work in that field? (Should I even bother talking about male writers in female-dominated fields, or would that be triggering?)

If women face so many barriers in the present day, why are such a huge percentage of major newspapers’ sports editors actually women? There are very few such editors in total, so the proportionality question becomes relevant. (It isn’t an example of tokenism.)

I find it suspicious that you did not survey female sportswriters who might disprove your thesis, like Mary Ormsby, Crusty Blatchford, or even (this is a bit of speculation) Mary Jollimore. Yet the subjects you did canvass plainly say they are leaving sexism behind them.

I simply don’t see any documentation of your handy-dandy academic’s claim that “the way female sports broadcasters speak is distinctly masculine, while their appearances are exaggeratedly feminine.” On the latter point, there’s only one Rachel Maddow and it’s unrealistic to expect all women on TV to look like her. Besides, I thought it was a central tenet of feminism to empower women to wear whatever they want without unwanted comment. I further thought that progressive journalists of your generation think that gender is a social construct, hence some women have penises and there is no such thing as a “distinctly masculine” way of anything.

Would you even bother writing an article about gay men in sports journalism, or are we not the right kind of victim for your preconceived narrative? Because that narrative is quite apparent here.

Are you further unaware that this topic has been documented *to death* for longer than you have been old enough to write a paragraph? In fact, couldn’t your article have been published at any time in the last 30 years, except for the pesky truth that the underlying conditions and facts have changed?