Illustration by Daniel Downey

In August 2016, Sean Fitz-Gerald was doped up on Percocet atop the dark brown couch in his rec room watching Black Mass when he got the first of two calls that changed his career path. He had broken his elbow while playing hockey the previous week and now found himself in a stupor, staring blankly at his TV. The injury and events that followed happened quickly—broken elbow on Saturday, surgery on Sunday, home by Monday. Coveted Tragically Hip tickets for the week after surgery had been reluctantly let go. Things weren’t going great for the award-winning sportswriter, and they were about to get worse.

“The Toronto Star calls and says, ‘Okay, we’re whacking you, but you get three months,’” Fitz-Gerald recalls. A year earlier, the Star had successfully hired him from the National Post, where he worked for 15 years with promises of an increased sports presence. “I loved working at the National Post,” he says. “I only left because the Star was expanding their coverage.” Now 40, Fitz-Gerald was a casualty of the retrenchment that has become so common at news organizations across the United States and Canada. He was one of 22 Star employees and 26 temporary staff axed that August.

Fitz-Gerald didn’t know it at the time, but being laid off actually cleared a path for him to become a central figure in a news experiment that’s disrupting sports journalism’s status quo. After leaving the Star, he spent a short period sussing the market out for new job opportunities but hadn’t found anything satisfactory. “That’s when Adam Hansmann called,” he says.

Hansmann, 30, and his business partner Alex Mather, 38, had been hard at work in a small San Francisco office trying to manufacture sports journalism’s future. After explaining how it might work, he offered Fitz-Gerald a job and the response was a resounding yes.

Hansmann and Mather had a compelling story. The pair surmised that sports journalism wasn’t dying, but that the old model definitely was. They first met while working for Strava, a website and sports app that monitors the athletic performance of its users. Hansmann worked on the business operations side of the company, while Mather was vice president of product management and design.

“When I heard Alex was leaving Strava, I said, ‘Okay, what’s he up to?” Hansmann says. “Alex filled me in on this idea that he had been noodling on for a new kind of sports media company, building off of what we learned at Strava and solving our own frustration as fans at the decline of quality sports journalism.” A few weeks later, Hansmann left Strava himself. The two set to work building the initial product and recruiting the group of writers that would help launch the sports media company now known as The Athletic.

The approach would be totally unlike the advertisement-based, newsroom-centered system that had been failing for years. The idea was to hire the best sportswriters across the U.S. and Canada to write for a company that would produce content free from advertisements or clickbait. Writers would have editorial freedom to pursue the stories they wanted to cover and be trusted to set their own schedules and write from wherever they liked. The Athletic would be completely digital and subscription-based; readers in Canada could either pay $10 per month or roughly $60 annually when the product originally launched, similar prices to what they charge today.

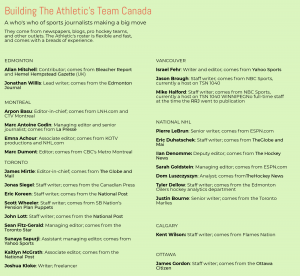

The company launched in Chicago in January 2016 which, as fate would have it, turned out to be the perfect time and place. Unbeknownst to Mather and Hansmann, one of the most compelling sports stories of the last century was set to unfold in the Windy City—the Chicago Cubs’ first World Series victory in 108 years. Spurred by the Cubs’ amazing run and the subscriptions it generated, Hansmann and Mather decided to expand. “Our goal is to establish a presence in the major sports markets on the continent,” Hansmann says. So far, the company’s coverage has expanded to include eight regions in the U.S., including such historic sports cities as Philadelphia, Cleveland, and Detroit. In Canada, the company has made similar moves, expanding into seven cities including Vancouver, Toronto, and Montreal. In Toronto, Fitz-Gerald was the fifth hire.

Hansmann says he and Mather funded the business on their own for the first four months, operating an office of just five employees. Neither took a salary for the first year, despite both getting married and working tirelessly. “Needless to say, we have invested considerable sweat equity into the venture,” says Hansmann, adding they’ve both “aged about 10 years since launching the site.”

Fortunately for them, the company’s expansion whetted investor interest. A Silicon Valley-based seed funder called Y Combinator (YC) gave The Athletic one of its initial outside investments of $120,000 in 2016. YC received a seven percent equity interest in exchange for its investment and partnership, which also included professional mentorship and access to the program’s alumni network that consists of companies like Airbnb, Dropbox, and Reddit.

In January 2017, a round of seed funding led by venture capital firm Courtside Ventures (CV) landed the company $2.3 million. Six months later, an additional $5.4 million was raised, which was once again spearheaded by CV. Hansmann and Mather refuse to release any subscriber numbers for The Athletic, but what they showed investors obviously instilled confidence in their vision for the company’s future.

In addition to the company’s up-front payment model, investment capital has allowed The Athletic to land some of North America’s most respected sportswriters. Ken Rosenthal, Tim Kawakami, and Sheil Kapadia, amongst others, put their faith in The Athletic, and in some cases, left top jobs to do so. Rosenthal, one of Major League Baseball’s best-known sports reporters, was forced to ditch his writing post at Fox Sports when the company switched to an all-video format. Kawakami spent 17 years as a columnist for San Jose’s Mercury News before joining The Athletic as the editor-in-chief of its Bay Area site. Kapadia, formerly the Seattle Seahawks beat reporter for ESPN, was a rising star who survived several budget cuts, but chose to join The Athletic because he says it offered him an opportunity to run the site’s operations in Philadelphia, his hometown.

Hansmann says hiring only reputable and trusted writers enabled the partners to focus on running the company’s business side, while leaving the editorial staff to control content. “Mostly, we attribute our success to the journalists we’ve successfully recruited, taking their careers into their own hands,” he says. “Our role at headquarters is to deliver the platform, fuel the venture with investment, marketing, and operational support, but the editorial staff makes it go.”

The company now employs around 100 full-time writers, none of whom report to a conventional office for work. Most set up shop at team practice facilities, or write from home or local coffee shops, allowing The Athletic to eliminate a substantial portion of the overhead costs associated with legacy media brands. Editors also work from remote locations.

Unlike many traditional media outlets, there are no wordcounts or article quotas. For the most part, writers are given the freedom to write about what they want. Because of this structure, most of The Athletic’s content differs from the cliché game previews and recaps, predictions, and listicles that dominate typical U.S. and Canadian sports pages.

So far, The Athletic’s unique business model appears to be thriving. In addition to the 21 local sites up and running in the U.S. and Canada, seven national sites are also operational, covering the National Hockey League, National Basketball Association, Major League Baseball, National Football League, National Collegiate Athletic Association football, and National Collegiate Athletic Association basketball. Another national site, The Athletic Ink, is dedicated to features and commentary. Though precise subscriber numbers are unclear, Toronto’s version is profitable and already has more than 20,000 subscribers says James Mirtle, the editor-in-chief of The Athletic’s Canadian operations. If that number was exactly 20,000, and every one of those subscribers took the cheapest option available on the website (C$4.79 per month), that would mean the company’s revenue in Toronto would be about C$1.15 million per year. Since Mirtle says the Toronto office only employs 12 full-time writers (some of whom also write for the national sites), and has no physical infrastructure, it’s not implausible to think that The Athletic has a profitable business model for the digital age. This seems especially likely in cities like Toronto, where there are large numbers of rabid sports fans.

“I’m a big believer in newspapers and I don’t want to see them die.”

“A lot in the coverage of us is a lot of skepticism. A lot of people saying this will never work,” Mirtle says. “I’ve had to deal with that since day one, since I joined The Athletic. It sometimes can be a little frustrating with the amount of success we’ve had and that continues to be the story.”

Hansmann and Mather are happy with the progress, but plan on continuing the company’s breakneck expansion. “We want to continue to grow market share in our existing markets,” Hansmann says, “and we want to add a few dozen new markets and verticals.”

In addition to winning readers and growing exponentially in a short time period, The Athletic has revived the careers of respected sportswriters across the U.S. and Canada.

“I had just gotten back from the Final Four and writing the national championship game story, so I generally did not think that I saw the writing on the wall,” says Dana O’Neil, a college basketball writer who was laid off by ESPN last April after a decade on the job. “I was pretty much blindsided.” After she was let go, O’Neil was hired by The Athletic’s NCAAB site—a relief since she wasn’t willing to relocate from her long-time home in Philadelphia. “I have kids that are teenagers and my husband loves his job,” she says.

O’Neil’s career began in the newspaper industry, working for the Bucks County Courier Times and Philadelphia Daily News in the early 1990s. Like O’Neil, Toronto’s Fitz-Gerald began his career in the newspaper industry, beginning with The Kingston Whig-Standard back in 1999. Their backgrounds point out the irony The Athletic faces: While throwing life preservers to sportswriters, it is also trying to overtake the market shares of the newspapers those same writers helped build.

In Kevin Draper’s October 2017 New York Times article, “Why The Athletic Wants to Pillage Newspapers,” Mather fired a warning shot to legacy media organizations across North America. He said The Athletic would “suck them dry of their best talent at every moment,” adding it would “make business extremely difficult for them.”

“We will wait every local paper out and let them continuously bleed until we are the last ones standing,” Mather told The Times, impervious to the fact that nearly all of his employees still had friends and family working at papers across the country. The company took an immediate PR hit as its own employees and the media took issue with Mather’s ruthless tone.

“I was a newspaper reporter for a long time,” says O’Neil in response to the Times article. “I’m a big believer in newspapers and I don’t want to see them die.” That said, she adds, she’s pleased with the open dialogue that has developed at the company since the article was published.

“I will say in [Mather’s] defence, and what’s cool about our company, is there were a lot of conversations, very honest ones,” she says about her colleagues’ reactions to the piece. “To his credit, he’s listened to what we said, he has returned phone calls, he’s apologized—I think—very sincere[ly], and I think he’ll be better for it. I’ve worked for a lot of newspapers and corporations that really could care less about what reporters think, so I’m definitely going to have his back, give him the benefit of the doubt, because I know he has ours.”

Other critics in journalism have been more pointed. “The famous interview that the founder did when he said his job was to kill newspapers made me gag a bit,” says Paul Chapman, deputy editor of both The Province and the Vancouver Sun. “Of course [journalism] is competitive, but there’s sort of a comradery and a spirit and that was sort of counter to that.” Nevertheless, Chapman understands where the entrepreneur is coming from, and the challenges facing The Athletic as it attempts to build a new business model that can succeed in a deteriorating industry. “There was an apology after and I’ll take that at face value, but I like the concept,” Chapman says. “I appreciate what they’re trying to do, and I welcome any good journalism that’s out there.”

Even so, Chapman acknowledges there is little evidence to suggest that the paywall model will take off. “ESPN has tried a subscriber model with their ‘Insider’ and I don’t think it’s been terribly successful,” he says, “and they have the best insiders and the biggest operation going.”

As for others in the industry, Chapman says colleagues’ opinions of The Athletic are mixed. “Some people scoff at it and just say people won’t pay for journalism,” he says. “There are people that think, ‘Oh, they’re neophytes—they’re not actually newspaper people, they don’t know what they’re doing,’ and then other people are intrigued. Everyone is waiting for the shoe to drop,” Chapman says. “Everyone is waiting for someone to come up with that model, and when it works I think everyone will sort of rush to adopt it, but right now [The Athletic] looks good, it sounds good, but I still think every venue has a way to go.”

Hansmann echoes Chapman’s thoughts, saying that Mather’s comments to The Times were simply a reflection of the dire straits in which sports media companies find themselves. “Most of the staff understands that we’re a start-up in a deeply troubled industry,” he says. “They wouldn’t have willingly left well-paying jobs to join our team if the founders were not competitive people who were going to work their asses off to see the venture through to success.”

The Athletic isn’t the first to attempt a remake of sports journalism. Mexican media mogul Emilio Azcárraga Milmo funded a sports newspaper in 1990 called The National Sports Daily, which was similar to The Athletic. Azcárraga enlisted Sports Illustrated’s Frank Deford—possibly the most respected sportswriter of his era—to be editor-in-chief. Deford was hugely successful at amassing a Rolodex of talented writers: Norman Chad from the Washington Post; Mike Lupica from the New York Daily News; Ivan Maisel from the Dallas Morning News; Leigh Montville from the Boston Globe; among others, all signed on to bring America something it hadn’t seen before: a daily newspaper dedicated entirely to sports.

“The famous interview that the founder did when he said his job was to kill newspapers made me gag a bit”

“It was the right idea at the wrong time,” says Peter O. Price, former president and publisher of The National Sports Daily. “The content was unique. The content was unimpeachable,” Price says, adding the project was burdened by inefficient distribution and high printing costs. The National Sports Daily folded in less than two years.

Nearly three decades later, Hansmann and Mather are trying to prove they have what eluded Price and Azcárraga—the right idea at the right time. All that’s certain is the economic model that once fuelled sports journalism—and not to mention journalism in general —is broken. Advertising has migrated to low-cost venues like Google and Facebook while consumers avoid paying for content wherever possible. The resulting revenue squeeze has forced significant cutbacks of sports coverage at digital giants like Yahoo, Fox, and Bleacher Report as well as at newspapers across North America. Some enterprises, like Grantland, have folded altogether.

More broadly, a 2015 study by Ken Goldstein, a media economics and trends expert, suggested there will be “few, if any, printed daily newspapers” by 2025. The report cited daily newspaper circulation in Canada, which went from around 50 percent of households in 1995 to 20 percent in 2014. If those declines continue, Goldstein says the five to 10 percent of households that remain in 2025 won’t be enough to support the print business model. Most people in journalism believe the future is online. The problem is how to realize it profitably, and so far, no one has a conclusive answer.

Though still in its infancy, The Athletic offers a glimmer of hope. Beyond the feel-good stories of career revivals for Fitz-Gerald and O’Neil, the company’s disruptive business model offers a new approach in an industry that desperately needs one. This past March, another major investment into The Athletic again showed the company’s unique model is making significant strides. The funding, which was led by Evolution Media and also included some previous early-stage investors, secured The Athletic another $20 million in funding, dwarfing the company’s early capital raises. The plan with the new funds, according to Hansmann, is to do much of the same. “We’re investing in our continued editorial expansion,” he says after the funding was made public. However, Hansmann also says that the new influx of capital will be used to develop other parts of The Athletic as well. He says they will use the money to support team growth at the company’s headquarters, and that they are also “keen to begin experimenting with other formats like podcasting, live events and possibly video.”

Given how the company has developed, it’s not shocking that Canadian operations leader Mirtle sees The Athletic’s potential in the sports world as on par with some of the great technological innovations of the 21st century. “When things like iTunes first launched, people thought it was a bit crazy and it would never work. When Netflix launched, people thought it was crazy because you could just go to Blockbuster,” Mirtle says. “There’s a lot of disruption happening in the world and a lot of it is ideas that people thought were crazy in the beginning. I think that The Athletic, from what I’m seeing, with how successful we’ve been so far, I think that we might qualify.”

About the author

Managing Editor, Business and Audience Engagement