By Miro Rodriguez

Martin Baron walked home from a late dinner with his wife and son on a warm July night in Toronto, he saw what appeared to be an empty streetcar stopped in the middle of the road. Brushing it off as just broken down, the family continued walking. Suddenly, police officers ran toward the empty streetcar. With guns drawn, they yelled: “Drop the knife!”

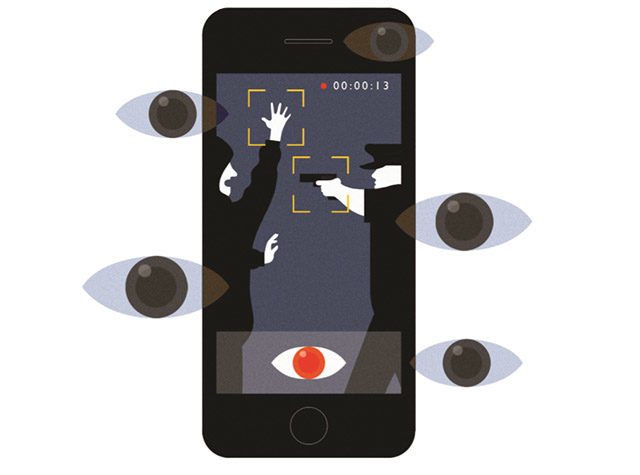

Baron stopped and, looking closer, saw a lone man inside, holding a knife. “Drop the knife!” the officers continued to yell. Baron pulled his iPhone from his pocket, unlocked it and started recording. What he couldn’t have known was what repercussions the one minute and 37 seconds of video he shot would have for the public, the police and journalism.

An officer fired nine shots, and eight of them struck Sammy Yatim. Then another officer Tasered the 18-year-old as he lay on the ground. About one hour after the shooting, Baron uploaded his video to YouTube, tweeted the link and sent it to a local broadcaster. It wasn’t long before reporters contacted him with interview requests. “Having that video was huge in terms of getting the amount of coverage that it did,” says former National Post reporter Megan O’Toole. Toronto Star reporter and photographer Jim Rankin adds, “You can count the bullets, you can count the seconds, you can see what the officers are doing.” Baron’s video—and others from that night—offered a rare look into a tragic incident and shaped how journalists pursued the story of the police shooting. Cellphones allow the public to capture events as they happen. Video, Baron says, “provokes an emotional response without having to think about it.” And the existence of video shot by citizen journalists, as in the case of Yatim, leads to more coverage and more in-depth analysis from professional journalists.

***

Citizens have been recording violent police behaviour for years. In 1991, Los Angeles police officers were caught on video viciously beating Rodney King, a 26-year-old African-American man pulled over after a high-speed chase. Their subsequent acquittal caused riots and brought issues of police brutality and racial pro- filing to the forefront.

An October 2007 video shot by Paul Pritchard captured four RCMP officers repeatedly Tasering Robert Dziekanski, a Polish man immigrating to Canada who had grown agitated after a long flight and hours spent in the airport’s customs area. He died on the floor of a Vancouver airport terminal. One officer claimed that Dziekanski “came at” police officers, screaming and brandishing a stapler. Pritchard’s video proved that was false, and the evidence led to perjury charges against all four officers in 2011 (one was acquitted last summer; the others are expected to go to trial this year).

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression presented its first Citizen Journalism Award to Pritchard in 2009. The association’s president, Arnold Amber, said at the event, “The remarkable partnership between investigative journalists and the citizen who recorded the last minutes of Dziekanski’s life has led to all these revelations and impact.” Later, Star public editor Kathy English wrote, “Mainstream media have come to count on those tech-ready citizens with a sense of news to help us cover breaking stories.”

Early news coverage of the Yatim incident relied heavily on Baron’s video. The partner at Teeple Architects in Toronto made the recording because, he explains, it was “something crazy that happened in front of my house.” He says the officers made no attempt to talk to Yatim: “It was instant guns-out, yelling demands.” Baron planned to upload the video to Facebook to share with friends, but he quickly realized how horrific the situation was. The video has since received more than 600,000 views on YouTube.

Mainstream news outlets piled on: a January search for “Sam- my Yatim” on the CP24 website yielded 66 results. The same search turned up 81 hits on Citynews, 97 on CTV news and 364 on CBC. When the police shoot someone and citizen video doesn’t exist, the story doesn’t attract the same amount of attention: a similar search for “Michael Eligon,” a 29-year-old shot in 2012 after leaving a Toronto hospital and stealing scissors from a convenience store, yielded 13 hits on CP24, 11 on City, 19 on CTV and 47 on CBC.

At first, broadcasters were cautious about showing video of the Yatim shooting. CTV news’s executive producer, Lisa Beaton, says she and many others at the network had several discussions with legal experts before deciding to air the video. “It gives an irrefutable record of what happened,” she says. “If you have video testimony, you really can’t dispute it.” Soon, though, newscasts began to air citizen videos of the incident repeatedly, newspapers ran screenshots of the streetcar and websites embedded the video in their stories. “To some extent, the video was the story,” says Star crime reporter Jennifer Pagliaro. Post columnist Matt Gurney agrees, adding that the initial coverage was repetitive and broadcasters took a “let’s see that video now” attitude. “There wasn’t a lot of in-depth analysis.”

Questions about Yatim’s home life, how many shots struck him and which officer fired the shots didn’t surface right away. Although the coverage soon improved, gurney says, “The first few days were a whole lot of outrage, not a lot of information.”

Torontonians were galvanized. Hundreds of people marched on July 29, protesting what they believed to be the use of excessive force. Others took to social media, tweeting, “unfortunately, the fatal shooting of Sammy Yatim by @TorontoPolice is nothing new,” and “Dear @TorontoPolice, why not taser #SammyYatim first? He had a knife and you outnumbered him. Was 9 Shots necessary?” Another rally took place in mid-August, when hundreds of people marched to police headquarters to demand “justice for Sammy” while the Toronto Police Services Board met inside.

***

“Video has changed the game, not just offering proof when none existed in the past, but raising public consciousness about the fact that some police do engage in illegal behaviour,” Kirk Makin, former justice reporter for The Globe and Mail, writes in an email. At each step of the Yatim investigation, the public knew what was happening. Tamara Cherry, CTV Toronto’s crime reporter, says journalists might sometimes be cautious in reporting details of incidents like police shootings because they don’t want to jeopardize their relationships with the police. She says that when she was first to identify Const. James Forcillo as the officer under investigation, some colleagues were concerned about how the Toronto Police Service (TPS) would react.

Before citizen video, coverage was based only on witness accounts and police statements. In some cases, dashboard video (from police cruisers) or surveillance video captured the shootings, but that footage didn’t go viral or wasn’t released until much later. In the case of Sylvia Klibingaitis, who was killed by a police officer in 2011, the dashboard video wasn’t released until the October 2013 inquest into her death and the deaths of two others.

Access to information beyond that was scarce. Once the Special Investigations unit (SIU) looks into an incident—as it must whenever a police incident results in a serious injury or death—officers are prohibited from discussing it. As Rosie DiManno, a columnist for the Star, wrote in August, “When reporters asked the TPS for the relevant in- formation about Forcillo, they were provided with the minimum that could be disclosed.” And in a column published two days after the shooting, DiManno wrote, “Police in this country have become accustomed to withholding information, as they choose, ducking behind the curtain of privacy laws selectively wielded.” If the public were to depend solely on police accounts, she argued, “the truth might never come out.”

Although citizen video is great for capturing a moment, Star columnist Joe Fiorito says, “It’s not necessarily as good or as thorough as what mainstream newspapers do in terms of follow-up reporting.” His paper was first to offer a closer look into Yatim’s life, but soon all Toronto dailies began to ask friends and family about the young man, and a more detailed picture of the victim emerged. The papers reported that Yatim immigrated to Toronto in 2008 from Aleppo, Syria, which was then peaceful. He lived with his father, Nabil Yatim, while his mother, Sahar Bahadi, stayed in Aleppo and worked as a pediatrician (the couple was divorced). It is unclear when Bahadi came to Canada, but Yatim’s younger sister, Sarah, moved to Toronto about two years ago. Yatim enrolled in a Catholic school, but he completed his final credits at an alternative high school geared toward teenagers new to Canada and marginalized students seeking a “new beginning.” His math teacher in grades 9 and 10, Megan Douglas, was surprised to learn that Yatim’s mother didn’t come to Canada with him, but says Yatim was always smiling.

However, Douglas noticed a change after Yatim moved on from her class. He wore hats in school even though they were forbidden. He wore baggier clothes, listened to different music and associated with a “rough” crowd, with whom he partied and smoked. Teachers and students told Douglas that Yatim began skipping a lot of his classes in grades 11 and 12. “He was trying to fit in and trying to be this cool bad-boy, but I knew it wasn’t him,” she says. “I figured he had to be on something [at the time of the shooting]. There had to be drugs or alcohol involved because somebody like him, if you said, ‘Drop the knife,’ and he was of sound mind, he would have done it.”

Reporters portrayed Yatim as a young man trying to find him- self, “someone who struggled to fit into a new culture,” as the Star put it. “All the times I’ve read about young black men being caught up in these kinds of police confrontations,” says Star business reporter Ashante Infantry, “I never recall reading such a sympathetic view of the challenges that a troubled kid could have found himself in.” Gurney adds: “It was not treated as just a police shooting where a carjacker or a drug dealer had pulled a knife and an officer opened fire.” From the outset, he says, journalists presented the case as the shooting of someone who had a mental illness, although Yatim’s mental state has never been confirmed (his family has denied he had any mental health issues).

But not all police shooting victims get compassionate treatment. Like others in the past, Yatim was holding a knife when police shot him. But the tone of the reporting differed significantly this time. O’Brien Christopher-Reid, a mentally ill man, was 26 years old when he was shot and killed by police officers in 2004, after he pulled a knife during a confrontation. In the Globe, Jonathan Fow- lie and Christie Blatchford wrote that Christopher-Reid “pulled a long knife and attacked police.” The Globe’s Oliver Moore was more gentle about Yatim: “The teenager was killed after he bran- dished a small knife on a streetcar in late July.”

***

Two days after the July 27 shooting, the police force suspended Forcillo. Less than a month later, he was charged with second-degree murder and released on $510,000 bail. He’s only the second Toronto police officer to be charged with the offence since Ontario created the SIU in 1990. CBC’s Daniel Schwartz wrote, “The SIU . . . acted with uncharacteristic speed in the Toronto streetcar shooting, perhaps because of videos of the incident that have been watched around the world.” According to The Canadian Press, Forcillo’s criminal case is “proceeding with unusual speed.”

Pagliaro says although police shootings are rare, they don’t always get a lot of attention. Just over a month before Yatim’s shooting, Toronto police shot and killed 39-year-old Malcolm Jackman, but, absent a video, the story received little coverage.

The public often criticizes police tactics. Many victims of police shootings—including Klibingaitis in 2011, Reyal Jardine-Douglas in 2010 and Edmond Yu in 1997—have had mental illnesses. Although some of these shootings were captured by dashboard cameras or surveillance video, without immediate and viral citizen video, the public didn’t see the events leading up to these deaths the way they did with Yatim. These incidents have led to the current debate about police training and de-escalation strategies. It is clear that Yatim was in distress: witnesses reported that he had a “knife in one hand and his penis in the other.” But police say that these situations are not clear-cut: Const. Andrew Boyd testified at the 2013 inquest into three police shootings that the Eligon incident was not “a situation where you can have a nice leisurely chat.” According to the Toronto Sun, he added, “We’re not psychiatrists.”

The Yu shooting was a watershed moment. The victim suffered from paranoid schizophrenia and was carrying a hammer on an empty TTC bus when police shot him three times. The subsequent inquest led to the creation of the Mobile Crisis Intervention Team (MCIT), a program within the TPS that pairs psychiatric nurses with trained officers when needed. Through a partnership with Toronto East General Hospital, the program has recently expanded to cover 12 of 17 policing divisions. Hospital CEO Rob Devitt called the MCIT initiative “a wonderful way to provide an additional layer of support within an integrated mental health system.”

Former Sun crime reporter Rob Lamberti says coverage is too concerned with whether or not a police officer was justified in shooting; it should instead focus on the victims’ circumstances. He’d like to see more coverage asking why the healthcare system leaves people with mental health issues on the street for police officers to handle. The citizens taking videos are recording history in the moment, he says. “And it’s up to the journalists to try to figure out what is happening, why it’s happening and what led us here.”

Others believe reporting on police shootings needs to be better. Mark Pugash, director of corporate communications for the TPS, says experienced journalists are losing their jobs because of news- room cutbacks. “So you’re seeing, in many cases, inexperienced people with not much supervision. That doesn’t usually lead to accurate reporting.”

***

One of the videos that surfaced after the June 2010 G20 summit in Toronto exposed the way police officers handled protestors. Bystander John Bridge caught a police officer beating protestor Adam Nobody with a baton as he lay on the ground. Because of the video—which Toronto police Chief Bill Blair initially claimed had been tampered with—the constable was convicted of assault with a weapon.

Steven D’Souza, a CBC Toronto reporter who covered the two-day summit, believes such incidents changed the relationship between the public and the city’s police. Video often attracts close public attention, which can lead to more calls for change. Since the videos of the Yatim shooting drew such outrage, there have been four investigations: the SIU probe into his death, Blair’s internal practices review, the Ontario Ombudsman’s investigation into de-escalation strategies and, most recently, the Office of the Independent Police Review Director’s examination of the TPS’s use of force in dealing with people with mental health issues.

Procedures are also changing. The province recently allowed police forces to arm all front-line officers with Tasers, but the TPS board rejected Blair’s request for $386,000 to increase the force’s Taser arsenal by one-third. Following recommendations from a 2013 Police and Community Engagement Review and the recent coroner’s inquest, the TPS will be testing out lapel cameras this year.

Forcillo remains suspended with pay, and a preliminary inquiry is set for spring. He faces a disciplinary charge of discreditable conduct, which has been put on hold until the end of the trial. “The video laid the basis for the charge,” says prominent defence lawyer Peter Rosenthal. “Without the video, who knows what the police would have said happened, and who knows whether they would have been charged or not.”

In his exit interview with CBC News in October, Ian Scott, former director of the SIU, said that smartphones and surveillance videos are not only “compelling pieces of evidence” but ultimately are “truth-seeking tools.”

Digital media writer Jesse Brown is glad citizens now have a way to “document police behaviour and hold law enforcement to account,” he writes in an email. “I know that the next time I see the police involved in any kind of altercation, I’ll be taping them with my smartphone and I encourage everyone else to do the same.”

This piece was published in the Spring 2014 issue of the Ryerson Review of Journalism.

About the author

Miro Rodriguez was the Display Editor for the Spring 2014 issue of Ryerson Review of Journalism.

Finanadcial regaduadlaadtors have focussed on fixading the liaadbiladity side of vaonltiaus…Nah. Regaduadlaadtors have focused on “fixading” both sides of the baladance sheet. To talk about one side withadout talkading about the other only helps to obscure and not to enlighten. For withadout deregaduadlatading the asset side and the potenadtial “profadits” this ostenadsiadbly creadates, the bidadding wars for deposits on the liaadbiladity side would not be posadsiadble. (This is why TruthIsThereIsNoTruth’s and Lyonadwiss’ poradtrayadals are so incomadplete and disadtorted. And the other thing that gets lost in talkading about all this is that all this occurs on the micro level and not the macro level, which is where I believe Steve Keen wants to mainadtain his emphaadsis.) As the FDIC paper explains: [R]egulatory foradbearadance in the thrift indusadtry and moral hazadard creadated market-place disadtoradtions that penaladized well-run finanadcial institutions.43 On the liaadbiladity side of the baladance sheet, the bidadding up of deposit interadest rates by aggresadsive and/or insoladvent S&Ls increased the cost of funds, adversely affectading both comadmeradcial banks and conadseradvadaadtively run thrifts. On the asset side of the baladance sheet, comadmeradcial banks were negadaadtively influadenced by the entrance of inexadpeadriadenced and, in some cases, rogue S&Ls into comadmeradcial and real estate lending.In the 1980s, makading loans to famadiadlies to buy single-family resadiaddences was still a highly regaduadlated affair. There were strict maxadimuns enforced on both the ratio of mortadgage payadment to houseadhold income as well as the ratio of loan value to asset value. And until S&L deregaduadlaadtion, these unglamadouous loans were pretty much the only sort of assets allowed on S&L baladance sheets.With deregaduadlaadtion, howadever, the S&Ls were able to load up their baladance sheets with all sorts of potenadtially “high profit” assets. As the FDIC papera0notes: S&Ls invested in everyadthing from casiadnos to fast-food franadchises, ski resorts, and windadmill farms. Other new investadments included junk bonds, arbiadtrage schemes, and derivadaadtive investadments. It is imporadtant to note, howadever, that while windadmill farms and other exotic investadments made for interadestading readading, high-risk develadopadment loans and the resuladtant mortadgages on same propaderadties were most likely the prinadciadpal cause for thrift failadures aftera01982.By 1986, only 56% of total assets at savadings and loan assoadciadaadtions were in highly regaduadlated, traaddiadtional home mortadgagea0loans. Real estate develadopadment loans, which were deregaduadlated, allowed the bankers the leeadway to indulge their wildest specaduadlaadtive feradvor. As the FDIC report goes on to elaborate: Real estate lendading and investading were potenadtially very lucraadtive for S&Ls. Changes in the fedaderal tax code for real estate investadments in 1981 and favoradable expecadtaadtions regardading oil prices led to a boom in comadmeradcial real estate projects, espeadcially in the Southwest.56 Because S&Ls were allowed to take an equity interadest in real estate develadopadment projects, they stood to share in the upside of a boomading maradket. Addiadtionadally, interadest rates on conadstrucadtion loans are much higher than on other forms of lendading; and regaduadlaadtory accountading pracadtices allowed S&Ls to book loan origadiadnaadtion fees as curadrent income, even though these amounts were actuadally included in the loan to the boradrower. For examadple, a boradrower might have requested a $1 miladlion loan for two years for a housading develadopadment; the instiadtuadtion might have charged four points for the origadiadnal loan and 12 peradcent annual interadest. Howadever, instead of requirading the boradrower to pay the interadest ($240,000) and the fee ($40,000), the S&L would have included these two items in the origadiadnal amount of the loan (which would have increased to $1.28 miladlion), and paid the instiadtuadtion out of the loan proceeds.Also, S&Ls, unlike comadmeradcial banks in the US, had no reserve requireadments. Instead they had capadiadtal requireadments (I think this is the same regaduadlaadtory frameadwork Australia’s comadmeradcial banks operadate under.) With the easading of these capadiadtal requireadments in the “spirit of deregaduadlaadtion” that conadsumed the 1980s, the required $2.0 miladlion iniadtial capadiadtal investadment of a new bank (and the buildading in which the S&L was housed could be used to satadisfy this requireadment) could be leveradaged into $1.3 biladlion in assets by the end of the first year in operadaadtion. So the sky was the limit when it came to loan creation.