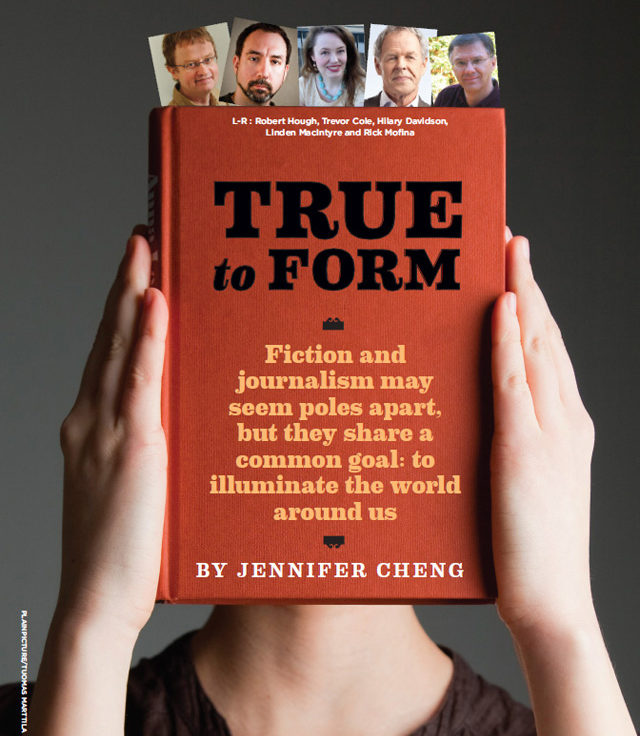

By Jennifer Cheng

It’s September 1982, and Linden MacIntyre has just sneaked into the Shatila refugee camp in Beirut with his camera crew and a taxi driver. Lebanon is in the midst of a civil war, and a week earlier, Christian militia had slaughtered hundreds—possibly thousands—of Palestinians. As the CBC broadcast journalist watches a front-end loader excavate body parts from a demolished residence built of cinder blocks, a baby’s hand falls at his feet. Looking up, he sees the aftermath of the massacre in the faces of the teenage boys who witnessed the slayings. It hits him that what happened here will reverberate throughout their lives forever.

Later that day, MacIntyre does his stand-up on location, then flies to an editing suite in Israel, where he and a colleague produce an eight-minute segment for The Journal. Years later, he realizes that he hadn’t even scratched the surface. “The story is larger than the moment. The story is how violence alters the DNA of an individual and society,” the 70-year-old says in his office at the Canadian Broadcasting Centre in Toronto. “The roots of violence in the 21st century are deep into the 20th century and possibly before that.”

The winner of 10 Gemini Awards, MacIntyre has co-hosted The Fifth Estate since 1990. He got his start in print journalism in the ’60s and spent much of the ’80s covering the Middle East, Central America and the Soviet Union for The Journal. As a reporter, however, he can’t use all of his material; the “excess,” as he puts it, is emotionally and psychologically toxic. “I reached a point in my life where there was an awful lot going on in my head and it was making me unhealthy,” he says. “When I became a journalist, it never crossed my mind that journalism would put me in a mental and emotional state that required me to turn to fiction to sustain myself in a spiritual way, but it did.”

The themes of MacIntyre’s journalism found deeper expression in his novels. Starting with 1999‘s The Long Stretch (followed by the Giller Prize-winning The Bishop’s Manin 2009 and 2012’s Why Men Lie), his Cape Breton trilogy explores the impact of violence as a secondary phenomenon, like second-hand smoke. “You can suffer from the consequences of violence simply by being in the presence of someone close to you who was damaged by violence,” he says. Cape Breton was the perfect setting—“a place that seemed to be untouched by violence but was nevertheless subliminally scarred by it”—despite being worlds away from the places that inspired the series. “I consider my novels to be books of journalism as well as works of fiction.”

The two forms may seem contradictory: journalism requires strict adherence to the facts, while fiction requires the writer to make them up; journalism is time-stamped, fiction is timeless. But they share a basic objective. As American author Paul Auster once told The Paris Review: “Novels are fictions, of course, and therefore they tell lies (in the strictest sense of the term), but through those lies every novelist attempts to tell the truth about the world.” Many great novelists have expanded on the work of journalists, probing injustice and conveying profound messages to a wide audience.

In the 1940s and ’50s, publishing a novel was the dream for many writers. By the early ’60s, however, journalists began applying elements of fiction—scenes, dialogue, climax, plot and character development—to their reporting, to equal effect. This approach, once known as New Journalism, is what Timothy Taylor, a journalist and novelist who writes for Air Canada’s enRoute magazine, calls “that big shake-up.”

Popularized by writers like Tom Wolfe, Hunter S. Thompson, Joan Didion, Norman Mailer and Gay Talese, it broke down the cold, objective reporter’s voice “into a much hotter set of personal experiences through which the world was glimpsed,” Taylor says. This alternate form became another means of vivid storytelling. Now, both avenues are equally relevant: journalism informs, fiction enlightens.

Rick Mofina, a crime novelist, saw his first corpse while working as a reporter for the Calgary Herald in the fall of 1989. A dark green Sedan had rolled off the Deerfoot Trail and landed on its roof in the ditch; the driver was a man in his early 20s. Mofina, then 32, left a note for the paper’s day staff, who produced a short story and ran an obituary—and nothing more. “That’s what the business calls for, but it should go beyond this,” he says. “And I think that sort of forged this desire for me to go a little deeper than what you do in daily journalism.”

His second novel, Cold Fear, was inspired by a case he reported on for the Herald in the early ’90s. A 13-year-old girl (and her black poodle, Cookie) had gone missing in the Rocky Mountains, where she’d been camping with her parents. That night, it snowed, and she was wearing just a T-shirt and jeans. When Mofina started heading back to Calgary days later, the girl still had not turned up and investigators had given up hope.

Then he got a call to go back to the mountains. She had been found in a trapper’s cabin, where she’d survived on packs of soup and kept warm by cuddling her dog. The RCMP had been investigating the family—a routine in such cases. “That went off like a bell in my creative memory,” he says. Cold Fear explores the disappearance of a 10-year-old girl in Montana’s Glacier National Park and a multi-agency task force’s massive search for her. In the novel, the parents look awfully suspicious to the FBI.

“You can be inspired by a case that was reported publicly, but I certainly was not writing at all about the real people involved,” Mofina says. “You shouldn’t be writing about real, private people.” Instead, the characters from his novels are part of him. His 16th novel, Whirlwind, published in March, explores how a community reacts to tragedy and how a reporter fulfills professional and ethical obligations in the face of it. It’s inspired by his experience covering floods, forest fires and school shootings. For instance, he was one of the first Canadian reporters on the scene after the Columbine massacre on April 20, 1999.

Fiction allows Mofina to serve creative justice, expanding on cases that would otherwise halt with the news cycle and writing the endings that don’t always pan out in reality. “In my novels, there’s hope in the end for the people who’ve endured the worst,” the 56-year-old says. “In real life, families are left grieving.” His novels come with an implied contract for readers: they’ll get a “thrill ride,” but they won’t feel bad afterward. “I wouldn’t say happy ending, but all my books end the way they should.”

New York-based crime novelist and freelance travel writer Hilary Davidson describes a similar dynamic between her fiction and her journalism. The locales the 42-year-old reports on add drama to her novels. As a honeymoon columnist for Martha Stewart Weddings, her job was to “spin a fantasy” for readers and advertisers, but her interests—and her imagination—went deeper than that.

Later, while in Peru on assignment for Glow magazine, she went to Machu Picchu. Looking out over the breathtaking site in the mountains nearly 8,000 feet above sea level, Davidson saw intrigue. There were no handrails on the glorious stone staircases, and few security officers; someone could easily be pushed off. In 2012’s The Next One to Fall, the second book of the Lily Moore series, a woman falls to her death while ascending one of those unguarded staircases. In Davidson’s upcoming novel, Blood Always Tells, she looks at how a perfect setting can make a murder look like an accident.

Although journalism can provide rich themes and rich material for fiction, the inverse is also true: writing fiction can make for better journalism. A piece Trevor Cole wrote for a magazine appeared on a Friday, and by Monday one of his sources had been fired. “It didn’t bother me that this had happened to him,” Cole says. “In fact, I felt quite righteous. I felt I had done an excellent job with the story.” He says his source shouldn’t have told him the things he did. The interview was “the ultimate get.”

In 2004, he published his first novel, Norman Bray in the Performance of His Life. Cole had relished the “assassin’s glee” as a journalist, but this was the first time he’d explored a protagonist—in this case, one based on his father—to such a great depth, which fostered a greater sense of understanding and empathy. “Novels force an in-depth relationship with your characters,” the 54-year-old says. “You’re going to spend a lot of time with the characters in your novels, so you do have to understand what’s going on in their minds to write about them effectively—and you do have to empathize with their point of view.”

Today, the author of three novels would still quote the source who got himself fired, because the material supported the article’s theme. “But I certainly wouldn’t be gleeful if what I wrote had that kind of negative effect.” For example, in 2006, Cole thought he had enough material to write his Toronto Life profile of CBC Radio’s Stuart McLean, so he didn’t dig for any possible dirt about the Vinyl Cafe host’s personal life. “That might not have been true early in my career,” he says.

Of course, moving from journalism to fiction has its difficulties. Growing up, novelist Robert Hough never had much interest in current events or magazines, which is a strange thing, the 50-year-old concedes, given that he would go on to make a living as a freelance magazine journalist for 12 years. But it was a job he enjoyed while he figured out how fiction worked. (Tom Wolfe once distinguished between two camps of journalists: scoop reporters, who competed with others to “get a story first and write it fastest,” and feature writers, who saw “the newspaper as a motel you checked into overnight on the road to the final triumph”: the novel.) “Journalism was good in that it kept me alive, and I met a lot of editors that way, so I could get people to read early stabs at novels,” Hough says. “But in terms of helping me learn the form of fiction writing, it was a liability.”

Once he began writing fiction, Hough had to unlearn a lot of habits. Exposition works differently in the two disciplines: in fiction, “you can’t explain anything. It’s got to read like it’s dropped from space. You are shooting through a different lens.” In journalism, you are constantly drawing attention to yourself as a reporter. “If you draw attention to yourself as a writer in fiction, you are dead. It just doesn’t work. There is a person present in the article: the person who is writing it.”

But the same writer animates both forms—the same material, too, according to MacIntyre, who says it’s just a matter of refining similar techniques. “You learn how to go deeper into people’s hearts and minds. That’s all. But you use the exact same experience.”

Now that he’s completed his Cape Breton trilogy, MacIntyre is working on his first stand-alone novel, set for publication in 2015. It was informed by his work as a journalist in courts and prisons across the country, and deals with the conflict that can arise when a judicial verdict contradicts popular opinion.

Journalism has given him a great ear for dialogue and a great eye for a story—and introduced him to a broad range of experiences and personalities. In short, it helped him to understand the world he writes about.

“I only wear one hat,” he says, “and that’s storyteller.”

About the author

Jennifer Cheng was the Departments Editor for the Spring 2014 issue of Ryerson Review of Journalism.