On November 20, 2014, Tim Duncan received an access to information (ATI) request. As executive assistant to the minister of transportation and infrastructure, he was asked for all records relating to the Highway of Tears, a 724-kilometre stretch of B.C.’s Highway 16 between Prince George and Prince Rupert where, by some estimates, over 40 aboriginal women have been murdered or gone missing. He searched his emails for “Highway of Tears,” yielding over a dozen results.

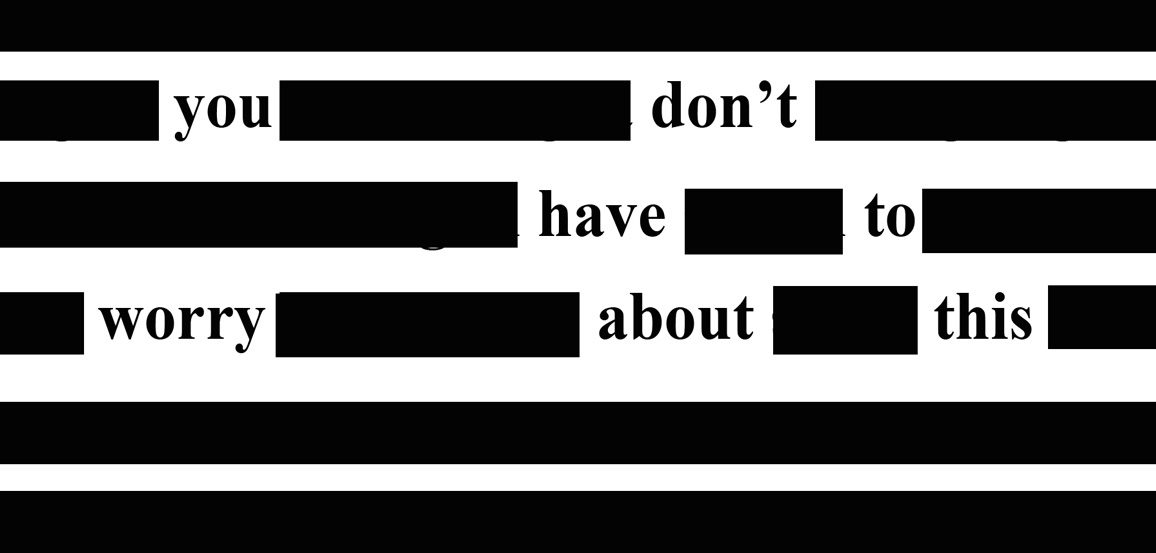

Duncan, then a new employee, says he quickly alerted fellow ministerial assistant George Gretes to the records. Gretes said, according to Duncan, “You got to get rid of these.” Duncan hesitated, at which point he remembers Gretes taking his mouse and keyboard from him, moving them to the corner of his desk and permanently deleting the records. “Hey, you don’t need to worry about this anymore,” Duncan remembers Gretes saying. “It’s done.”

A year later, Duncan’s account of the incident (wholly denied by Gretes) was published in a report by B.C.’s information and privacy commissioner Elizabeth Denham. “I am deeply disappointed by the practices our investigation uncovered,” writes Denham, and she’s not the only one.

Canada’s ATI system has long been criticized by journalists for its bureaucratic complexity, extended wait times and prohibitive fees. Though the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act guarantees each citizen right of access to any record in the custody of a public body (with notable exceptions including trade secrets and personal information), Denham’s investigation has exposed a culture of secrecy within certain branches of government. The fact that this scandal centred on a request about missing and murdered aboriginal women—an issue already exacerbated by years of government inaction—makes it all the worse.

Duncan, who says he wanted to go public with his story sooner, instead put it off until he left his government position months later. He says coming forward while working for the government would have been “career suicide.”

In the aftermath of last year’s elections, journalists have amplified their demands for reformed national and provincial freedom of information policies. According to the National Freedom of Information Audit, which Newspapers Canada conducts annually by filing nearly 450 requests at the municipal, provincial and federal level, Canada’s 32-year-old federal Access to Information Act has been “effectively crippled as a useful means of promoting accountability.”

Along with the outright deletion of records, Denham decries what she calls “oral government,” in which decisions are made in person and no written record is created. Government employees are also allowed to broadly interpret exemptions to the freedom of information act, which are meant to be used only in specific cases, and often liberally redact even innocuous documents.

The Access to Information Act, implemented in 1983 under Pierre Trudeau, was written for a paper-centric government and hasn’t aged well. At a time when important public information exists in many forms–much of it online–scandals such as B.C.’s point to the need for an updated framework with clear guidelines for the preservation of electronic formats such as email in the face of ATI requests.

But institutional change, however long overdue, would only address part of the ATI problem. In his letter to Denham, Duncan stresses that what happened to him was not an isolated incident but rather a sign that the government doesn’t respect the public’s right to know. And while many civil servants across all branches of Canadian government work diligently in the name of free information, Duncan’s testimony—along with decades of newsroom gripes—has emphasized that many don’t.

When it comes to ATI, the government’s system is only as strong as the conviction of those who comprise it. The hope among journalists is that, as out-dated ATI policies become reformed, so too will outdated attitudes promoting government secrecy.

Stay tuned as the RRJ continues to tackle problems with Access to Information next week.

About the author

Jonah Brunet is copy and display editor for the Spring 2016 issue of the Ryerson Review of Journalism.