Scrolling through Twitter one afternoon last September, I came across an account that stood out in an alarming way. “In Iraq killing Shias, etc.,” said the bio of @MuhajirSomali, a supposed Canadian member of ISIS. While I don’t know what he meant by “etc.,” he certainly was claiming he was in Iraq killing Shias and others. His posts were terrifying and I wanted to break the news, so I took a screenshot of his bio. On my Twitter feed I posted: “The #Canadian ISIS member says on his bio on Twitter that he is in #Iraq to kill Shias. #ISIS #NO2ISIS #Canada.” I attached the screenshot as evidence to tell my more than 4,000 followers what this fighter said he was doing in Iraq.

At that time, @MuhajirSomali had fewer than 500 followers on Twitter. My post would amplify his message. But I am far from the only journalist to draw attention to the purported activities of ISIS online. The shocking nature of these posts makes them difficult to ignore.

@MuhajirSomali, along with a second Twitter handle @muhajirsumalee (both now suspended), allegedly belonged to Farah Mohamed Shirdon, a Somali-Canadian from Calgary in his early twenties. He first appeared in a viral April 2014 video, in which he and other foreign fighters burned their passports in a campfire while chanting, “Allah is great” in Arabic. Their threat to North Americans was explicit: “We are coming to you and we will destroy you with Allah’s permission. . . . With Allah’s permission we came to you with slaughter.”

ISIS has become infamous over the past year for its massacres and kidnappings in Iraq and Syria. The extremist group has been fighting a parallel propaganda war on social media. ISIS members use platforms including Twitter, YouTube and Facebook to send their messages and aim for videos of beheadings and other hateful acts to go viral.

The chilling videos showing the beheadings of journalists James Foley, Steven Sotloff and Kenji Goto make another message clear: reporters who go to conflict zones in Iraq and Syria are risking their lives. This makes finding local sources and conducting firsthand research challenging. Without on-the-ground sources, it is tempting for journalists to lean on social media, seeking out users who claim to be ISIS members.

Individual news organizations must decide if and how to use these sources, but the risks in doing so are great. It’s a difficult task to verify that these people are who they claim to be and it’s easy for those reporting on the online activities of ISIS to get the story wrong. Worse, when journalists reproduce social media messages by anonymous ISIS sources without adequate context, they can sensationalize the story, playing into the hands of those who want to spread fear.

***

A decade ago, I went to Iraq. My parents were born and raised there, and I wanted to see the places of their childhood memories. While they had lived there under a dictatorship, the situation during my visit was even more volatile. Sectarian violence, kidnappings, assassinations and car bombs emptied whole neighbourhoods of Baghdad. Al-Qaeda-affiliated militants, other armed groups and militias caused chaos and fear, disrupting lives in an attempt to enforce a fundamentalist understanding of Islam. At this time, ISIS was still allied with Osama bin Laden and known as Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI).

Black banners mourning the deaths of young men and women flew all over the city. Two years after the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq, I sat on the pavement under the blazing August sun in Baghdad, a witness to a mortar attack that targeted civilians. The ground underneath my feet shook and the sound pierced my ears. A few minutes later, a child rushed to her mother. “I saw their slippers soaked in blood. There were pieces of flesh,” the crying girl said. Unlike most who lived there, I was witnessing such a horrific scene for the first time.

A year after my visit, AQI renamed itself ISI, adding the “S” in 2013 for al-Sham, the Arabic name for Syria, to reflect its cross-border territories. In northern Iraq, ISIS seized control of the cities of Fallujah and Mosul in its brutal campaign to control the Muslim world. The group targets Iraq’s Shia majority and leaves a humanitarian crisis in its wake. Last spring, around the same time Al-Qaeda severed ties with the group, ISIS dropped the geographically specific part of its name, rebranding as Islamic State to reflect its heightened ambitions.

In its current campaign, ISIS has become adept at using social media to build a fearsome brand and has recruited young men and women from different parts of the world, including Canada. Ten years ago, militants recorded video and audio and sent it to mainstream news outlets in hopes of getting airtime. Today, they have direct access to an audience through platforms including Twitter, Facebook and YouTube to boast about acts of brutality and make threats.

Sometimes their messages are worth reporting—it would have been difficult to ignore the graphic beheadings and mass executions, or the kidnappings of thousands of Yazidi women and children. But there’s an ethical dilemma: does the coverage serve ISIS propaganda designed to terrorize people?

***

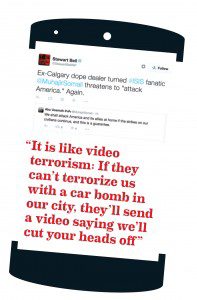

Stewart Bell, a senior reporter specializing in foreign affairs and national security for the National Post, frequently covers foreign fighters, especially those who join extremist groups. In his Twitter bio, he describes himself as a “journalist and author who writes about Canadians who do stupid things in the name of their causes.” Currently, many of his subjects are ISIS members or supporters, and Bell uses Twitter a lot—tweeting, retweeting and reporting on the posts from those claiming to be ISIS members. Authorities estimate that over 100 Canadians are fighting in Iraq and Syria, though not all are supporting ISIS.

On September 16, 2014, the Post published a front-page story by Bell with the headline, “Unmasked Canadian Jihadist Tweets His Deadly Ideology.” Online, it was even more succinct: “Canadian Jihadist Unmasked.” The story revealed the identity of Abu Turaab, who had been tweeting threats and exhorting people to join the fight in Syria from the handle @AbuTuraab. “While he has been careful not to reveal his real identity, posting only photos of himself wearing ski goggles or with a scarf covering his face,” wrote Bell, “the National Post has learned he is a 23-year-old Canadian citizen named Mohammed Ali.”

The article, illustrated with images pulled from Twitter, addressed the phenomenon of Canadians travelling to Syria to fight for ISIS, and built a profile of Abu Turaab through his Twitter posts. They included an exchange following Foley’s execution in which he threatened Bell: “I wonder how my homie

@StewartBellNP feels after watching the latest IS video?”

The article didn’t say how the Post confirmed the identity behind @AbuTuraab. As a reader, I was left with an article based on Twitter posts of someone who is allegedly a terrorist. To me, Abu Turaab remains an anonymous source since he doesn’t publicly reveal his identity. There is no way to ensure it’s Mohammed Ali posting and not someone pretending to be him.

Bell doesn’t see it this way. I have been following his reporting on ISIS and I have one main concern: it’s too easy to pretend to be someone else online. Consider the supposed Syrian blogger behind Gay Girl in Damascus from a few years back who turned out to be an American man studying in Scotland. In a more recent incident, Indian authorities arrested 24-year-old engineering student Mehdi Masroor Biswas, who was running the pro-ISIS Twitter account @ShamiWitness. Biswas had more than 17,000 followers (including jihadists), a following cultivated from his home in India.

When I meet with Bell to discuss his use of ISIS Twitter accounts, he tells me social media offers insight into the minds of those who travel to Iraq and Syria to fight. “This is the first conflict where journalists have been able to follow people who have gone to participate,” he says. “And this allows us to identify who they are, where they are, what they are, what they are seeing and also their thinking, their justification for doing what they are doing.”

He acknowledges identities can be manipulated online, but believes verification of certain ISIS fighters is possible. “Most of the ones that are very active on social media, with few exceptions, they don’t want you to know who they really are,” he says, admitting that it’s challenging to identify someone when they don’t post photos showing their face. “When somebody does that and they go overseas, then inevitably there are people here who know who they really are.”

Still, there’s no way to ensure it’s always the same person posting from a Twitter account. Abu Turaab changed his Twitter accounts as each one was suspended, making his trail difficult to follow. (The threatening nature of ISIS accounts violates Twitter’s terms of service, so they are routinely shut down.) If Abu Turaab and others are misidentified, the whole story could be wrong.

Bell says he verifies information from a Twitter source such as Abu Turaab before publishing by doing traditional reporting, speaking to people who know about him or his activities. But Canadian journalists have been wrong before. In August 2014, several journalists reported the death of Canadian-born jihadist Shirdon based on social media posts of ISIS members or supporters. On August 15, 2014, a Post headline declared: “Farah Mohamed Shirdon, Calgary ISIS Fighter Reportedly Killed in Iraq, was ‘Dead Inside’ Long Ago, Friend Says.” CBC reported the same story: “Farah Mohamed Shirdon of Calgary, Fighting for ISIS, Dead in Iraq, Reports Say.” As did The Calgary Sun: “City Radical Dies in Iraq—Third Young Calgarian Killed Fighting with Extremists.” A month later, Shirdon was resurrected in a Skype interview with VICE Media co-founder and CEO Shane Smith. In a room with other combatants, Shirdon claimed he was in Mosul alongside 10,000 to 15,000 fighters. He added that he was motivated by the Qu’ran, rather than a recruiter. Throughout the interview, Shirdon maintained his smile. To me, it seemed like a wicked, mischievous expression suggesting those who believed his death were fools.

Verification is a foundational principle of journalism, and news organizations lose credibility when they get stories wrong. Craig Silverman, author of Regret the Error and an expert in journalistic accuracy, says reporting unverified news lends authority to an idea that may or may not be true. Even when news organizations use hedge language in reporting on a rumour, he says, they provide it with wider distribution and an element of credibility. The boundary between fact and fiction becomes blurred.

On June 23, 2014, Shirdon appeared in an article on VICE’s science and technology vertical Motherboard. Benjamin Makuch, an editor with a history of engaging with ISIS sources online, wrote the piece. He believes verification can be achieved by reporting and correlating social media accounts—many militants are on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter—though they remain essentially anonymous. “You have to go with the best information you have available,” he says.

Even when their identities cannot be verified, messages from ISIS present problems. Makuch believes pursuing these stories is worthwhile because ISIS is inherently newsworthy, even if its motive is to disseminate propaganda. He cites the example of the news of Foley’s beheading, which originated from ISIS social media posts. “You can’t actually question the news value of something like that,” says Makuch. As a journalist, he would report on the “horrifying image” because “it needs to be known.”

VICE’s willingness to publish Shirdon’s viewpoint provides an uncritical platform for the sensational messages of ISIS. When the Foley video first circulated online, a headline I saw on the Toronto Star website—“Foley Execution Video Going Viral Is Exactly What ISIS Wants”—summed up what I was thinking.

The more people share videos of beheadings, the wider the spread of ISIS’s threat. Louie Palu, a Canadian documentary photographer and photojournalist who has worked in Afghanistan, says he is reluctant to go to Syria. It’s not the fear of death, but the possibility of being kidnapped and used by militant groups that makes it dangerous.

He is repulsed by the spread of the beheading videos. “It is like video terrorism,” Palu says. “If they can’t terrorize us by doing a car bomb in our city, they’ll send a video saying, ‘We’ll cut your heads off.’”

Susan Sachs, foreign editor at The Globe and Mail, says her newspaper does not post videos or stills of beheadings or any other horrific killings. Her reason is straightforward: “We don’t provide a platform for anyone, whatever group they are, to put out their propaganda.” CBCNews.ca features writer Andre Mayer doesn’t use ISIS Twitter posts as sources, though he may refer to them during research. “[Twitter posts] are 140 characters, so you aren’t getting a lot,” he says. “You don’t know the person behind any given tweet, really.” Mayer’s sources instead are analysts, institutions and universities because he believes they offer more credibility and sophistication.

Including a range of Muslim voices, rather than focusing on the tweets of extremists, can provide less sensational and more nuanced reporting. Religion is an important issue to address, since ISIS members claim to be following teachings of the Qu’ran.

Imam Syed Soharwardy, founder of the Islamic Supreme Council of Canada, routinely speaks to reporters about the diversity of Islam. He points out that ISIS members belong to the fringe Wahabi sect. “These terrorists should not be identified as Muslims. They should be identified with their sects,” says

Soharwardy. “Do not associate that person with the religion of 1.6 billion people.” A reader with no knowledge of Islam may not necessarily understand the difference between a fanatic who commits crimes in the name of religion and the rest of the Muslim population. Sensational coverage has the effect of promoting an insidious form of Islamophobia.

On the more fundamental question of ethics in reporting on ISIS’s threats and boasts on social media, I spoke with Jeffrey Dvorkin, director of the journalism program at University of Toronto Scarborough. Dvorkin counsels extreme caution in reporting on the online activities of ISIS. “There is a very fine line between giving an organization publicity and hearing their point of view in order for the audience to understand what the organization is about,” he says. “A journalist’s obligation is to make those difficult choices to help the audience understand who these people are without necessarily giving them a free ride.”

Journalists risk crossing the “fine line” when reporting on atrocities that could be labelled as war crimes. Broadcasting an unedited video or post and giving the perpetrators the chance to talk about it amplifies their message. Context is crucial, says Dvorkin: “It is possible, I think, under certain circumstances, to report on stories overseas from Canada, but with a warning that some of the information can not be verified.”

***

Reporting on what ISIS members do without being their mouthpiece is challenging—even according to readers. On September 29, 2014, the Post published on its letters page responses to the question “Should the media be reporting on what jihadists are posting on social media?” The replies varied: “The public has the right to know”; “The media is giving them what they want”; “It depends.” The same discussion goes on in newsrooms as journalists try to figure out what to report and what not to report.

ISIS’s weapons on the ground are guns, bombs and mortars, but social media is its conduit to the rest of the world—a tool for spreading fear and recruiting new members. It’s also, unfortunately, one of the few windows available to North American journalists looking to understand what’s happening in Iraq and Syria. But it offers a distorted view of the conflict, mediated through the self-

interest of the aggressors—a necessary fact to keep in mind when making decisions about if and how to report on social media messages from ISIS.

“There is a great value in being on the scene and being a reporter and witnessing events firsthand, even though it’s extremely dangerous,” says Dvorkin, pointing out how little we know about ISIS beyond the violent headlines. But that may not be a good reflection of reality on the ground. “If we are trying to understand them, we need to do more than report on what they are tweeting.”

Art courtesy Chris Tucker

About the author

Yusur was the head of research and writer for the 2014-2015 issue of the Review. She was a second year MA of Journalism student and a freelance journalist with keen interest on politics and human rights. Yusur is a Twitterholic!