In Quebec, Julie Snyder is a superstar. She’s been on TV for over 30 years and has hosted her own talk show in France. She’s worked on the mega-popular Quebec reality shows Star Académie, La Voix (Quebec’s officially licensed version of The Voice), and Le Banquier (the Quebec Deal or No Deal). But many outside Quebec know her primarily as the now-ex-wife of Pierre-Karl Péladeau, who ran the media giant Quebecor until March 2013 and was elected Parti Québécois leader two years later.

The uncomfortable intersection between media ownership, power, and public service that makes up Péladeau’s résumé is a story in itself. But for Snyder’s part, she and Péladeau had been together for 14 years and had raised two children before deciding to marry in an elaborate Quebec City ceremony in the summer of 2015, only to announce their divorce five months later. Initially, neither discussed the split openly. But in spring 2016, when she presented a prize at the Gala Artis with Guy A. Lepage, host of the popular Radio-Canada talk show, Tout le monde en parle (TLMEP), Snyder finally relented.

In the 12 years since Lepage’s popular talk show first came on the air, he had been campaigning to get Snyder on as a guest. She had always refused, reportedly out of loyalty to TVA, the Quebecor-owned channel that aired most of her shows. But that tie was now severed.

As they stood together onstage — Lepage dressed in black and navy, Snyder in a kicky, colourful Gucci dress with pink sleeves and a high yellow collar — Lepage said, “You know, next Sunday is the final episode of Tout le monde en parle. It might be fun if you wanted to come on.” The audience reacted with cheers even before he finished the suggestion.

Snyder feigned ignorance, insisting that she had no new projects and wouldn’t have anything to plug on the show. “Frankly, I don’t know what we would even talk about,” she said. The audience laughed enthusiastically, and both TV personalities smiled mischievously at the camera. “We might be able to think of something,” Lepage deadpanned.

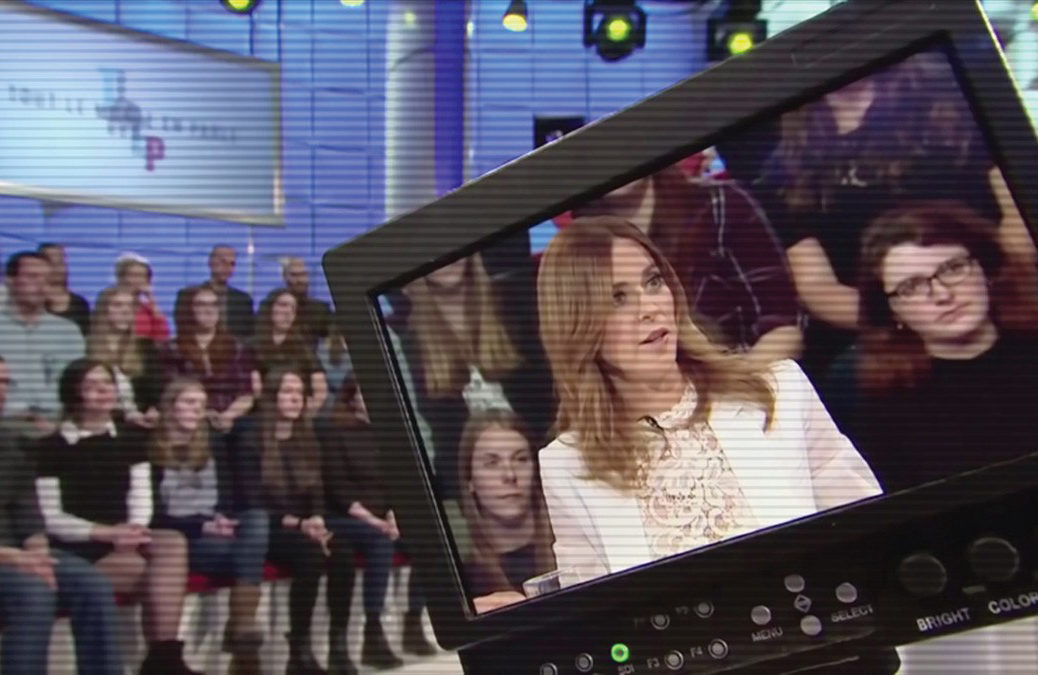

On May 1, 2016, 1.7 million people watched as Snyder finally appeared on Tout le monde en parle’s season finale. After a jokey reference to those awards, she launched into one of the most candid, reflective interviews that Tout le monde en parle had ever broadcast. The cameras remained fixed on Snyder almost the whole time, even as she sat silently listening while Lepage and his co-host, Dany Turcotte, asked questions. Part of her candour seemed to come from the familiarity that existed between her and the interviewers; despite the rivalry between their networks, there were frequent references to people they had both worked with, to shared experiences in the tight-knit world of Quebec media.

Even when Lepage and Turcotte’s questions were intimately personal — what’s it like being in mediation with someone whose reputation as a union-buster gave him the nickname, “King of the Lockout”? — she responded in a way that felt honest. Lepage and Turcotte shared the interview, but it was Lepage — approachable but shrewd, with a high forehead and a neat goatee — who asked most of the questions. Turcotte, smaller and more jovial, tends to provide levity.

Undeniably, the stage belongs to Lepage; he always begins and ends the show. But Turcotte is more integral than the sidekicks on American late-night shows. The two have an easy rapport, frequently addressing each other with comfortable shorthand and occasionally trading good-natured barbs.

As interviewers, they know when to ask probing questions, but they usually also know when to hang back. The Snyder interview featured more than a few long pauses as she searched for the right words. Lepage and Turcotte treated her with warmth in a way that went beyond the kind of amiability that’s expected of TV hosts. It felt like they were on her side in the contentious personal and professional relationships she was describing. At one point, they jokingly suggested she get into politics and run against her ex: “You’re more popular than him, you know.” Still, they were willing to press her on the finer points of her contract, of her divorce mediation. Snyder had clearly shown up ready to talk, and the TLMEP interview gave her a prime opportunity.

The response the next day was bombastic. Le Journal de Montréal published a list of her top 14 “citations à coeur ouvert” of the night — quotes from an open heart. “It’s a historical moment on the show,” Huffington Post Québec reported. It was all over that day’s editions of big papers like the Montreal Gazette and La Presse, as well as free dailies like Metro; it was a top story even on English-language CBC radio. Then, that afternoon, Pierre-Karl Péladeau — a man so thin-skinned and single-minded that a comedian who once mocked him in a two-minute-long sketch was immediately red and allegedly blacklisted — stepped down as Parti Québécois leader. He cited family reasons.

Péladeau’s retirement didn’t last long; he returned to Quebecor as CEO less than a year later. But after winning the PQ leadership race by near-record numbers and vowing to “make Quebec a country” in his first speech, the sudden withdrawal from politics was a shock.

There’s “no question” that Péladeau’s resignation was the result of Snyder’s interview, says Brendan Kelly, an entertainment columnist for the Montreal Gazette. “Look at the timing. The Tout le monde en parle interview was like a nuclear explosion.”

On that same episode, Quebec filmmaker Xavier Dolan gave a breezy interview, occasionally pausing to joke around with the other guests or to take a drink from the glass of champagne in front of him. But one of the questions posed by Lepage gave Dolan pause: did he think his new movie, Juste la fin du monde, deserves the Palme d’Or, Cannes Film Festival’s top prize? Dolan took some time before answering. “That’s a trick question,” he said. Lepage fixed Dolan with a cajoling look, urging him to give a good answer. “On est entre nous,” Lepage told Dolan in a placating tone. It’s just us here.

He’s joking, of course. An average episode of Tout le monde en parle draws in 1.3 million viewers. But, like a lot of Quebec media, the show is made for an eager and a specific audience. It doesn’t have to try accounting for the difference in opinion between Nova Scotians and Albertans; it doesn’t need to try to be all things to all Canadians. In a way that’s rare in this country’s media, the show is made for an “us” that’s clearly defined.

Kelly says that anyone with a little knowledge of French can learn a lot about Quebec culture and politics by tuning in to TLMEP; he even thinks that the rest of the country might do well to try out a similar program. The panel show is a common format for news and comedy in the United Kingdom, but English-speaking Canadian TV has never seriously tried it — at least, not as successfully as TLMEP.

“I see no equivalent forum in English Canada,” La Presse columnist Patrick Lagacé wrote in a 2014 piece about Tout le monde en parle for The Globe and Mail. The show, which has aired Sunday nights since September 2004, dominates Quebec’s media landscape. It has a simple–enough structure: Lepage and Turcotte sit at wide tables in the middle of a studio, with audience members seated across from them. Drinks are served. Guests come out for individual interviews but often talk to one another as much as they talk to the hosts. They discuss the week’s news, promote their work, and consider current events — cultural, social, political. It often hosts Quebec stars like Marie-Mai and Jean Leloup, and occasionally international ones: Taylor Swift, Monica Bellucci. In the weeks leading up to the October 2015 election, Tom Mulcair, Gilles Duceppe, and Justin Trudeau all made stops on the show. Over the last decade, it’s been a place where Quebec public life has played out. In an increasingly relevant way, it’s also an outlet that’s significantly affected the news it comments on.

Toward the beginning of Jack Layton’s second TLMEP interview, which aired four weeks before the 2011 federal election, the then-NDP leader misused a French expression. In response to a question Lepage posed about the French language outside Quebec, Layton described NDP Member of Parliament Yvon Godin as un Acadien féroce. It translates literally to “a ferocious Acadian,” but the French adjective carries a more savage, animalistic meaning than in English. It’s rarely applied to a person. “Un Acadien féroce?” Lepage repeated, as the audience laughed. “Is [Godin] allowed to go outside, or do you have to tie him up?” Layton quickly accepted Lepage’s suggestion for an alternative word choice (batailleur, or fighter) and moved on. For the rest of the interview, Layton, who made his career in Toronto but was raised in Hudson, a mostly-anglophone Quebec community outside of Montreal, spoke in accented but solid French. He talked about his health, about the possibility of a coalition government in the upcoming election (he respected the Bloc Québécois but preferred to live in a united Canada that works for Quebec, he explained), and about his granddaughter (who, it turned out, has the same name as Lepage’s daughter: Béatrice). He was charming, affable. It would be easy for an anglophone politician to lose the audience after a French-language gaffe, but Layton didn’t; perhaps because Lepage laughed warmly and not maliciously through the entire segment, the crowd stayed with Layton the whole time. But there was also a certain irreverence, a spirit of fun that felt distinct from other interviews Layton gave during that election cycle. Even when Lepage and Turcotte were asking tough questions, it felt accessible in a way that interviews with politicians often are not.

Media commentators from CBC, Le Devoir, and Rabble have credited Jack Layton’s 2011 appearance as a significant reason why the NDP did so well in Quebec at that year’s election. The party won an unprecedented 59 seats out of 75; under Tom Mulcair in 2015, they held on to only 16. “It was considered decisive,” says political reporter Philip Authier, who writes for the Montreal Gazette. “That’s where people decided he was un bon Jack” — a good guy.

TLMEP is sometimes overtly political — federal party leaders will plead their case in election years. Candidates from the Liberal Party, the NDP, and the Bloc, as well as PQ leaders gearing up to replace Péladeau, all showed up in the fall of 2016. “When elections come around, every politician wants to be on that show,” Authier says. “You cannot expect to win without going on that show.” And outside of election campaigns, it’s fairly common for politicians to appear on TLMEP, or for the hosts to tackle political topics with their guests. “There’s more of a range than people might expect,” Kelly says. “They do entertainment stuff, but they also have politics, social stuff. They’ll bring on academics. And it does sometimes change the discourse.”

The Layton interview featured several of the show’s trademarks. There’s the “question qui tue,” the question that kills. The room goes dark and the lights dramatically sweep the studio before settling a spotlight on the guest’s face. (In response to the question—did he consider the Liberal party or the Bloc Québécois to be his main adversary in Quebec?— Layton answered that he had to watch out on both sides. “We’re playing two different games at the same time,” he said.) At the show’s end, Turcotte, in his role as “fou du roi”—court jester—presents guests with jokey message cards. In Layton’s case, the particularities of the show’s routines allowed audiences to process his message in an accessible way.

Layton “gained a lot from that interview,” says Richard Therrien, a TV columnist at the Quebec City newspaper Le Soleil. “TLMEP played a major role in that, definitely. He was clearly someone who had prepared, but it didn’t seem calculated in the way many political interviews do. It seemed very sincere, very natural. That setup was favourable for him.”

Therrien of that interview to Layton’s charisma—but also to a deliberate choice made by the show’s producers. “They weren’t aggressive,” he says. “They didn’t trap him in the way they’ve trapped other politicians in the past.” One such ambush happened during a disastrous 2007 interview with Mario Dumont, leader of the right-wing provincial party Action démocratique du Québec (ADQ). The interview was slightly challenging but fairly pleasant for the first 10 minutes. Dumont outlined the parameters of Quebec’s relationship to the federal government and remarked on a member of his party who had recently been criticized for racist comments. But the interview suddenly shifted after Dumont demurred on a question about the provincial budget. From backstage, a producer wheeled out a blackboard with budget categories as the hosts encouraged Dumont to lay out his party’s financial plan. At first, he was amused, although he didn’t engage. “I have a good memory, but not good enough for this,” he protested. Lepage, facing him at the table, pressed him: “You said your budget was better than the opposition’s, why not prove it?” Turcotte walked up to the blackboard, comically exaggerating his boredom. “Am I the only one working here?” he asked. The audience laughed. The conversation between Dumont and Lepage quickly grew uncivil, heated. After a commercial break, the next guest, journalist Chantal Hébert, joined the fray by declaring that Dumont demonstrated he “wasn’t ready to be premier and wasn’t ready for his exam.” After Dumont’s poor showing in the 2008 provincial election, his party accused Radio-Canada of being in the bag for the Liberal party, with TLMEP at the forefront of its complaints. For Therrien, Dumont’s treatment is an example of the show’s heavy-handed attempts at editorializing. On that episode, Hébert “was extremely severe, extremely hard on him,” Therrien says.

Tout le monde en parle’s stage provides politicians and entertainers alike with a platform that’s wide-reaching and influential. But as Dumont learned, those statements aren’t always received in the way they’re intended. In the days that followed Julie Snyder’s interview, the respect and adulation that had been so widely expressed for her began to give way to more critical takes. On May 4, Therrien reported that Snyder had been granted access to the tape of the interview before the show aired, access that would typically never be allowed. Therrien still doesn’t have a definitive answer as to whether that decision was justified. “If I were Guy A., I probably would have accepted,” he says. At that point in time, having Snyder on the show would likely be worth almost any condition her team imposed. Therrien says he has enough faith in the show’s process to believe it would not hand the reins over to an interview subject, even a powerful one. “Knowing Guy A. Lepage, he’s … how to say it … he’s fairly convincing, let’s say. There would have been negotiations,” Therrien says. “He’s going to stick to a certain standard of quality. So I don’t think Julie would be able to control the narrative the way she could on her own shows.” Still, he says, “Julie Snyder is someone who prepares enormously. She’s a TV pro, she knows how it works. It’s evident that this interview was prepared for.” Kelly agrees with Therrien. “Looking back, it’s hard to see it as anything but a carefully staged PR coup for Julie Snyder,” he says.

Before her appearance on Tout le monde en parle, police officer Stéfanie Trudeau was publicly reviled. Known by her badge number, “Matricule 728,” she gained notoriety during the spring 2012 student protests, when cell phone footage showing her pepper-spraying demonstrators was circulated. In the video, Trudeau’s movements are swift and surprising. She doesn’t warn the mostly calm group of protesters, one of whom is yelling but not moving, that she’s about to strike. After it happens, the man who had been yelling remains in the same spot, repeating the same words over and over: “Est-ce que je t’ai touché?” (“Did I even touch you?”) Behind him, two people offer handkerchiefs to another affected protester, who’s crouched on the ground, coughing as she rocks back and forth in pain. It would be a damning video even if the protests didn’t have widespread support within Quebec. At the time of Trudeau’s appearance on the show, in September 2015, she also was facing unrelated assault charges. (She was later found guilty.)

When she walked out onto the Tout le monde en parle stage, Trudeau was greeted with tepid applause; the room was actively hostile. Lepage and Turcotte asked provocative questions, but largely took the backseat. Trudeau fielded questions from other guests, including actor and comedian Patrick Huard (star of the 2011 lm Starbuck and 2006’s crossover hit, Bon Cop, Bad Cop), who glared at Trudeau and anxiously tapped his fingers against the table during the segment. Filmmaker Philippe Falardeau, director of Monsieur Lazhar, asked a politely worded question about police protocol that Trudeau answered tersely. Soon, the two were openly fighting. “I’m asking if you think at all about the reasons behind social disruption,” Falardeau said. Trudeau was disdainful. “We’re not there to—” she started, but he interrupted, jeering: “To think?” The audience reacted with surprise and glee; many people clapped. Trudeau continued to point out that the law must be respected, even if people disagree with it; Huard pointedly asked her if she would respect the rule of the law when her trial is decided. Lepage ended the interview by asking Trudeau if she has an anger management problem.

It was a thrilling, heated exchange—it was great TV. But many viewers didn’t think it was a fair interview. Even though the hosts, the guests, and the audience exhibited behaviour that was largely an expression of public sentiment, its severity on such a public stage struck many viewers as overly harsh. An uproar about Trudeau’s treatment erupted on social media, and the movie Huard and Falardeau were there to promote was threatened with boycotts. The appearance of a pile-on was likely what caused such a big public upset. “That’s one of the things you have to be very careful of in broadcast media,” Kelly says. If a guest appears to be under attack—even an unpopular guest—“the public is always going to sympathize with that person.”

Therrien sees the Matricule 728 interview as an unsuccessful attempt at the kind of editorializing the show attempted with Mario Dumont. “People have accused the show of wanting people to fail,” he says. “But if that was the intended goal, it wasn’t the goal that was achieved.”

Lepage told La Presse that they would have invited leaders of the student protest onto the same episode if their intention had been to attack or humiliate Trudeau. Falardeau and Huard have mostly avoided talking about the incident, and it hasn’t come up on TLMEP since.

The 2016-17 season, the show’s thirteenth, continues to feature the province’s biggest stories. The premiere included an interview with anglophone businessman Mitch Garber, who had just made a public plea for English and French Quebeckers to make more of an effort to culturally understand one another. Patrick Lagacé appeared on the show after news broke about the Montreal police’s surveillance of his phone. So did former child star Jérémy Gabriel, whose human rights lawsuit against comedian Mike Ward for mocking his disability launched a public conversation about when and how limits should be placed on freedom of expression. The show discussed the American election, Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government, Montreal’s upcoming 375th anniversary party (which Lepage is hosting). And lots of people were watching; the season’s ratings were consistently above one million viewers. When a late November conversation about health care led several of the show’s guests to criticize provincial health minister Gaétan Barrette, he took to Twitter to instantaneously respond to his critics.

In early December, Lepage and Turcotte welcomed Laval mayor Marc Demers to talk about Gilles Vaillancourt, one of his predecessors, who had just been sentenced to six years in jail after pleading guilty to fraud. This was great news for viewers of the show. It was a huge story, and Demers, a former police detective, had many insights about the case. But it was bad news for competing stations. The TLMEP team allegedly asked Demers for exclusivity, meaning he had to cancel all other scheduled appearances. This was particularly offensive to former ADQ leader Mario Dumont, who has worked as a TV host since exiting politics in 2008, and whose feelings toward the show haven’t warmed much since the disastrous chalkboard incident. (He currently hosts a show on the TVA-owned news channel, Le Canal Nouvelles.)

On his show, an obviously frustrated Dumont apologizes to viewers for not airing the Demers segment. “We asked for an interview with Mayor Demers, and we got an interview, and we would have shown it at this time,” he says. “But imagine, if you can, that Mayor Demers, the current mayor of Laval, was offered …” Here he pauses for effect, and leans into the camera, exaggerating his features, “a big show, a big talk show on another station. And they said, ‘Hey, you should only talk to us. Cancel everyone else.’” Then, silence: Dumont simply stares at the camera, without speaking, waiting for his words to sink in. He blinks. A beat, then another beat. “Ben, là,” Dumont says. “He said yes.”