If there’s one thing Marie Wilson wants us to remember, it’s that journalists are above all teachers, and accomplished teachers must first be educated. The process is simple: learn, then impart your knowledge in whatever medium you choose — whether it be broadcast, print, radio, social media or blog.

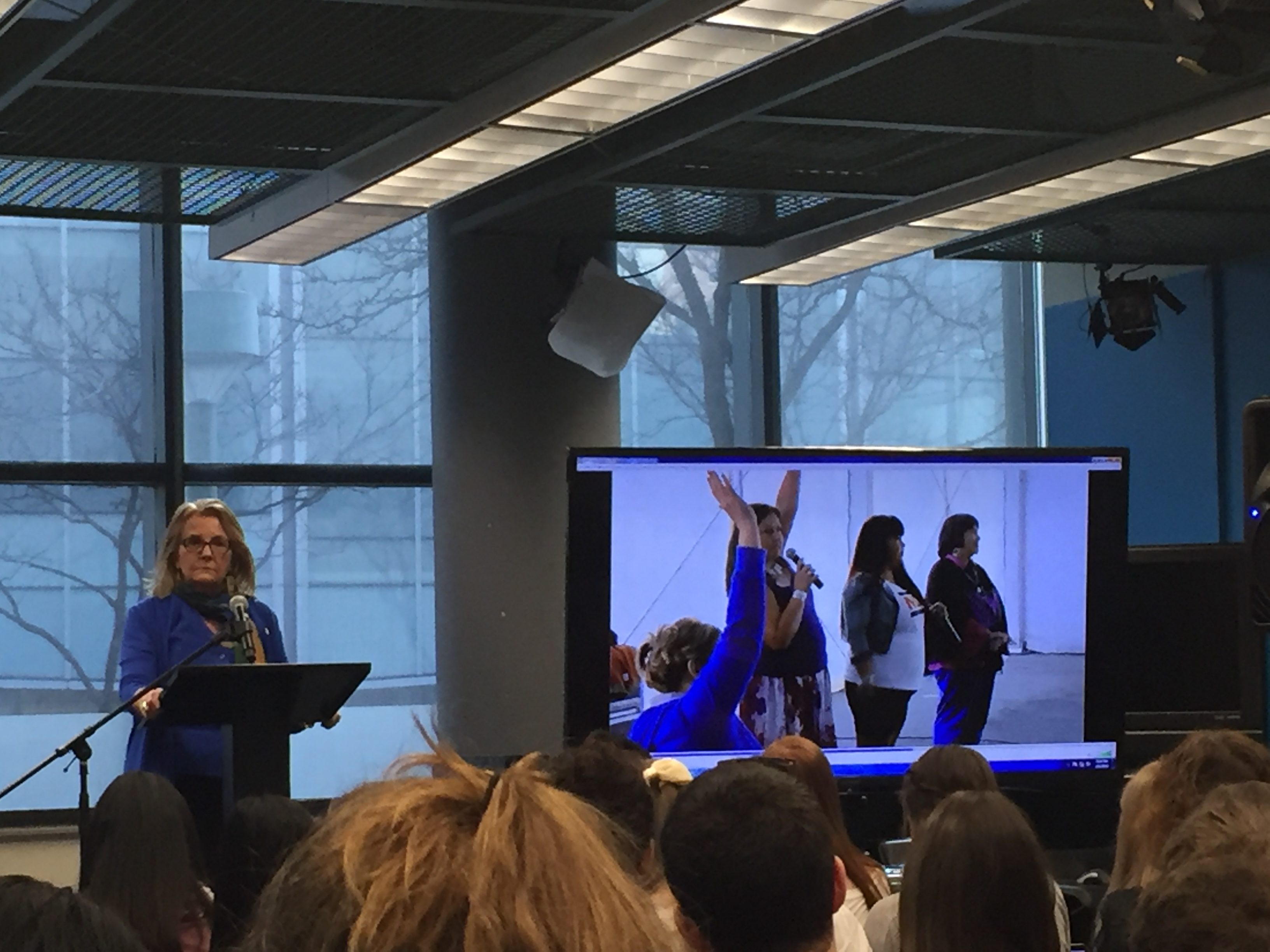

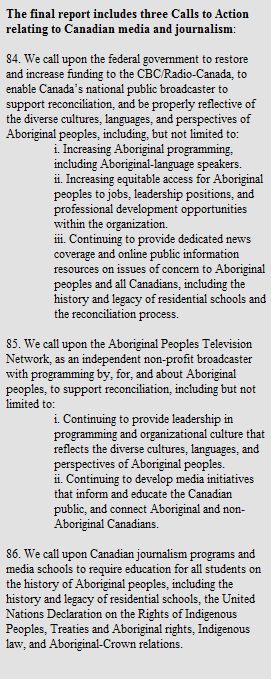

On Monday, Wilson, one of three commissioners on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), spoke to the Ryerson School of Journalism as part of the Atkinson Lecture Series. She highlighted three of the TRC’s 94 Calls to Action that specifically have to do with media and journalism.

If journalism is about learning and teaching, then Wilson calls the work of the TRC over the past six years “the greatest act of journalism ever.” As she developed the report, speaking to hundreds of indigenous people from across the country, Wilson collaborated with the two other commissioners in the same way that she would have worked with fellow journalists in a newsroom. She knows the feeling first-hand—she used to be a journalist, working for the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network (APTN) and later as regional director for CBC.

Canada needs to understand its history, Wilson says, and journalists are an integral part of that process. When she showed a video of testimonials from Aboriginal people who had been affected by residential schools, many in the audience at the Rogers Communication Centre brushed away tears. Journalists have to face these realities without flinching—to “keep looking until things change,” Wilson says. Reporters are the protagonists in this story, and ignorance the widespread antagonist. That’s why, first of all, journalism schools need to ensure that students are aware of indigenous culture and history.

Maybe that seems like a basic prerequisite, but knowledge about indigenous culture is not as common as it should be. Let me share a story.

During my first semester of journalism school, a student came to reporting class in her Halloween costume. She was wearing a tan, faux-leather dress, long braids and a feathered hat. Some students whispered that her outfit was inappropriate; others didn’t mind. My neighbour, a girl I hadn’t spoken with much previously, soon asked why some considered the costume so offensive. I explained that it had to do with showing respect for indigenous peoples—especially since we were in class on the land they used to live on, in a school whose namesake is a notable player in the creation of residential schools. She stared back at me blankly. Though she had grown up in Ontario her whole life, she didn’t know the story. She’d assumed that, before Europeans arrived in North America, the land had been empty.

I still think of that Halloween class now; it was scarier than any costume. Until that day, I had naïvely assumed that everyone—especially journalists, who are inherently curious and informed—knew at least the basics about Canadian history. In reality, we have a long way to go before the complex relationship between Canada and its indigenous peoples is understood by the majority. I can’t imagine how it would have felt to speak to that first-year student if I was aboriginal myself.

Candace Maracle, a filmmaker and journalist who also spoke at the Atkinson Lecture, remembers speaking with ill-informed colleagues in school and at work. Her parents are survivors of residential schools; her grandmother caught tuberculosis at one of the notorious institutions. Comments in the classroom or newsroom about Aboriginal Peoples’ education or alcohol problems used to hit Maracle hard. As a Mohawk woman, she says, it’s her duty to tell better stories than her colleagues would.

That’s why the TRC’s Calls to Actions are critical. The Ryerson journalism school is working on implementing them in classrooms, but current journalists and students should also be looking at them. After all, if we are meant to be teachers, then we first need to inform ourselves.

About the author

Viviane Fairbank is the Senior Editor of the 2016 issue of the RRJ.