By Amanda Panacci

It began with an aerial shot of a wheat field. The September 24 lead story on CBC’s The National recounted the horrific murder of three Aboriginal boys near Pefferlaw, Ontario, more than five decades ago. But the brief, beautiful opening visual was noteworthy because it was the first shot aired from CBC’s pilot drone journalism project. Manager of technical services Carl Swanston and resource producer David Kovacs have navigated through a lot of bureaucracy to get to this point. They chalk the drone’s premiere up to progress, knowing the device will soon offer much more.

Swanston’s excitement about drones is striking as he launches into the story of the Costa Concordia. The Italian cruise ship struck a reef off the island of Giglio in January 2012 and capsized, killing 32 people. When CBC’s the fifth estate investigated, the reporters relied on video footage from passenger smartphones. “Had we had a drone, could you imagine going into that harbour?” Swanston asks Kovacs. They would launch the drone from the shore and hover it over the ship to give viewers a look at the devastation inside. “It would’ve changed that show completely.”

Designed for military operations, Unmanned Aerial Vehic les (UAVs) also work for anything from mundane tasks—delivering pizza or dry cleaning, for example—to commercial surveillance of farmland. Journalists around the world are reimagining the limits of storytelling by using drones as a visual tool. The machines cover protests without compromising the safety of reporters and fly at low levels and into tight spaces that helicopters cannot reach. But drone journalism pits new technology against the public’s fear of being watched. The worry is that journalists will use drones to search out stories and compromise the privacy and safety of citizens.

les (UAVs) also work for anything from mundane tasks—delivering pizza or dry cleaning, for example—to commercial surveillance of farmland. Journalists around the world are reimagining the limits of storytelling by using drones as a visual tool. The machines cover protests without compromising the safety of reporters and fly at low levels and into tight spaces that helicopters cannot reach. But drone journalism pits new technology against the public’s fear of being watched. The worry is that journalists will use drones to search out stories and compromise the privacy and safety of citizens.

Classified as aircrafts, drones fall under Transport Canada regulations and require a Special Flight Operating Certificate (SFOC) for commercial operations, with some new exemptions added recently. Transport Canada, which issued 945 certificates in 2013, has seen a spike in SFOC applications. With the numbers steadily rising, Matt Schroyer, a journalist in Oklahoma and founder of the Professional Society of Drone Journalists, cites safety as an immediate concern. The technology is still developing, so there is always the possibility that a drone could lose control, drop out of the sky and smack a civilian in the head. When it comes to using drones for reporting, Schroyer says, an operator should be an experienced commercial pilot, or at the very least, possess technical knowledge of the device.

As of November 26, an exception has been made permitting commercial entities—including news organizations such as CBC—to forego the detailed SFOC application for drones weighing two kilograms or less. Since the certificate takes a minimum of 20 working days to process, flying a two-kilogram drone, such as the DJI Phantom 2 Vision, may seem like a journalist’s best option. But opinion remains divided on whether the regulations will offer much help for reporters covering breaking news. Ian Hannah, owner of the aerial photography business Avrobotics, says journalists would still need to be at least 9.26 kilometres away from an airport, creating problems for news organizations in urban settings. He adds that it’s a good sign that Transport Canada is slowly making changes to its regulations, but it may not be enough to be worth journalists’ extra time and effort.

Regulations are changing, in part, because of a demand for commercial operation. Preparing for a time when drones are commonplace, Jeff Ducharme, a photojournalism instructor at Newfoundland and Labrador’s College of the North Atlantic, has created a drone code of conduct for student journalists to follow. He incorporated drones into his course to give his students hands-on training, while also teaching them the importance of not turning the news into a video game. His code covers 21 points of ethics, law and operation. He stresses number four, which states that under no circumstances should they use a drone to search for stories. “Our biggest responsibility with this technology is to prove that we can operate it in a respectable, ethical and lawful manner,” he says. He created his code in June, but to his knowledge, no news organizations have adopted it yet.

In a survey this year, the Surveillance Studies Centre at Queen’s University found that only 12 percent of the public supported reporters using UAVs. Journalists are no strangers to breaking the law or crossing ethical boundaries, especially when it works to combat the competition. Ethicist Klaus Pohle says that news organizations should have a code of ethics that deal specifically with the technology. As a journalism professor at Carleton University, he watches the competitive nature of the business closely: If CBC uses drones, then CTV will most likely follow suit. “Media organizations are going to use whatever method is available to get the better story.”

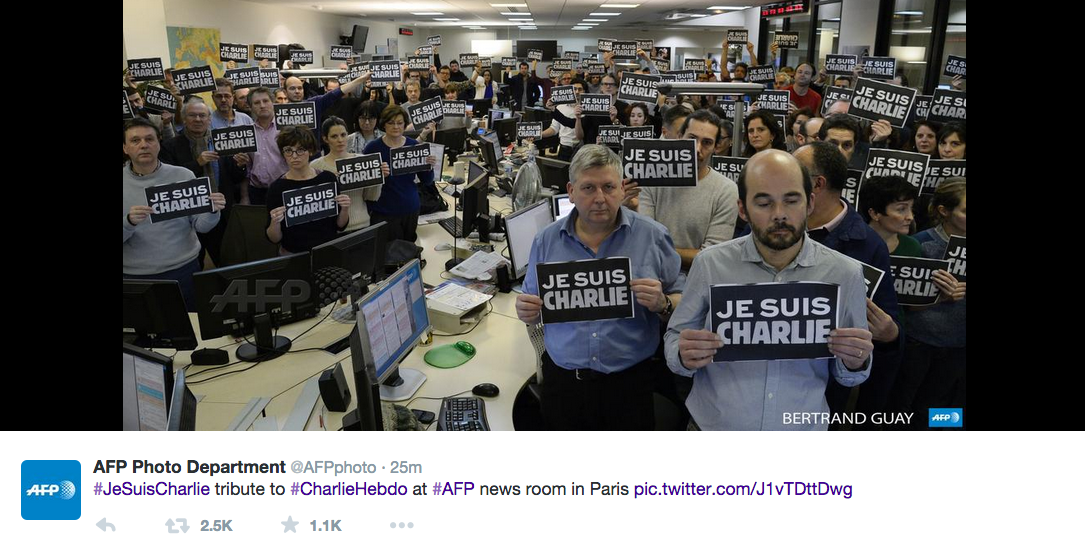

And if news outlets don’t, citizen journalists will. Hobbyists, a term Transport Canada uses to identify anyone who doesn’t profit from using a UAV, can do things with drones that journalists can’t because there are no regulations on hobbyists here—only safety guidelines. During the Hong Kong protests in October, a citizen hovered a drone at high altitudes to capture the thousands of youth crowding the streets during the Umbrella Movement—and reading about the number of people protesting is not the same as seeing the crowd take over the streets.

After illustrating the power of using a drone at the Hong Kong protests, Swanston recounts when the film crew for the fifth estate used a drone to zoom up on the barred windows of a garment factory in Bangladesh to report on its poor structure and unethical working conditions. Drones can deliver one continuous shot, one that goes against the standard quick cuts of broadcast news: a “big picture” view so powerful, no words are necessary. “I doubt that drones will create news,” Swanston says. He doesn’t want to overuse the device; he just wants to be able to use it for stories that would benefit from the in-depth visuals. The drone enthusiasts may not be there yet, but they aren’t giving up until the flying video camera becomes as mainstream as the smartphone.

About the author

Amanda Panacci was the Spring 2015 online editor of the RRJ