A large, silver-framed whiteboard with the names of the people killed in a December 2014 mass shooting hangs on the wall behind Otiena Ellwand’s desk at the Edmonton Journal. It’s December 2015, almost the one-year anniversary of the crime. Under the heading “Victims North” are the names of those Phu Lam murdered at his north-side neighbourhood home: Tien Thuy Truong, Elvis Lam, Ha Thanh Truong, Valentina Nguyen, Dau Thi Le…the list goes on. Written in a once-bold green marker, the faded names won’t come off. “It’s like it’s haunting me,” Ellwand says. Covering the largest mass killing in the city’s recent history would be a tough undertaking for any reporter, let alone one who had been at the Journal for just over a year.

The 26-year-old journalist is the first one to arrive at the paper’s downtown office each morning. Because of her 6:15 a.m. start, Ellwand is the only reporter there and must be ready to write about anything and everything. But over the past couple of years, she has also regularly covered police press conferences, developed contacts within the police force and earned a good reputation for her crime reporting.

Ellwand worked across from former crime bureau chief Jana Pruden, who resigned in January. She reports to the city and business editor, Mark Iype, who expects her to update web copy as news unfolds. When on assignment, she may get an accompanying photographer or videographer, but often doesn’t. The newsroom is trim, with about a dozen beat and general assignment reporters, and money is always tight. “Because we are so short-staffed,” she says, “a lot of the beat reporters have to write general assignment stories.” (In fact, one day, when I was shadowing Ellwand, Pruden mistook me for a new intern and called out, “Hey, are you busy working on anything?”) Ellwand makes herself valuable by interviewing, taking photos and shooting video—often at the same time. “When you’re a young reporter,” she says, “you definitely have to sell yourself as being versatile, adaptable and multi-talented.”

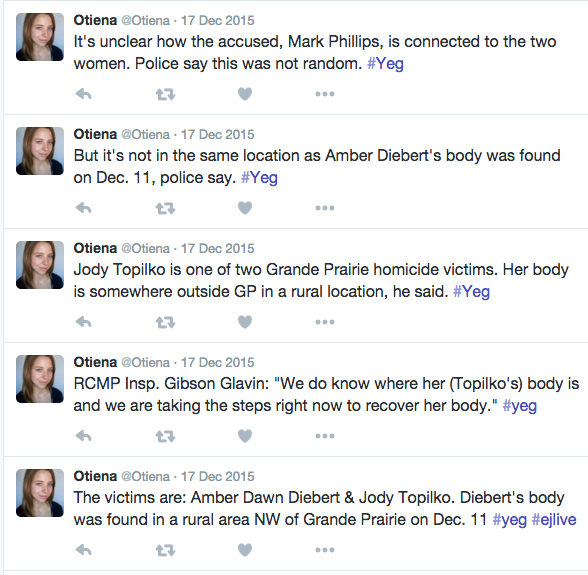

Just after 11 a.m. one wintry Thursday, Ellwand gets a press release from the RCMP that says police have charged a man with the murder of two young women in Grande Prairie, Alberta. After reading the release, Ellwand tweets: “A 28-year-old man from Grande Prairie has been charged with two counts of second-degree murder in the deaths of two women #yeg #ejlive.” Her co-worker Paige Parsons, who’s on the last week of her four-month contract position, writes a quick web hit, and Ellwand calls around for more information. She finds one of the victim’s parents in the phone book but can’t get the person to talk. After speaking to RCMP media relations, she learns that Global News is already headed to RCMP Edmonton headquarters for a quick press conference—and it starts in 20 minutes. Springing out of her cushioned chair, Ellwand reaches into a nearby desk drawer and grabs a set of car keys. She throws on her plum, knee-length parka, and she’s off.

Ellwand halts the Journal’s Nissan Pathfinder in a no-parking zone, gathers her notebook, iPhone and audio recorder, and jumps out. A reporter and camera-man from Global are the only others there for the press conference. They’ve already set up inside, but RCMP inspector Gibson Glavin is late. When he arrives, Ellwand shoots video on her phone while balancing an audio recorder. She listens attentively to him and interjects with questions. She notices holes in his statement and wants more information. The inspector begins to show impatience with all the questions—he says he’s already told them everything he can in the 15 minutes. “My time is precious,” a parting Glavin says to Ellwand and the Global reporter, “and so is yours.”

Back in the freezing Pathfinder, still illegally parked, Ellwand replays her audio and transcribes. She calls the Journal to update her co-worker, then emails the strongest quotes, which will go into an update on the web. She’s too busy tweeting on her phone to start the car and turn on the heat, even though I can see her breath when she speaks. Before pulling her seatbelt across her puffy, down-filled jacket, she expresses frustration with how hard it is to take notes while filming. She turns on the engine to head back to the office as light, crystal snow falls from the sky. The Journal gig is Ellwand’s first full-time reporting job apart from a one-year contract in New Brunswick. It’s a coveted position—she is one of the paper’s few permanent hires in the last couple of years. She has worked hard to make her way from intern to contract to staff, but she still doesn’t have her own official beat.

As newsrooms continue shrinking, the number of beats has dwindled. Structural reconfiguration and digital disruption have combined to create a completely different landscape from that of the pre-social media era. A new breed of reporters—the lucky, usually much younger ones filling the voids left by staff cutbacks—now cover specific interest areas in addition to general assignment duties. Beat reporting is not dead, but it’s now more loosely defined.

Newspaper editors, with fewer resources at their disposal, are prying as much output as they can from their reporters. It’s a stressful time for young journalists, but it’s also exciting. In this scrambled beat culture, the line between general assignment and specific areas of focus is blurring. Reporters such as Ellwand at the Journal, Ashley Csanady at the National Post and Kelly Bennett at CBC Hamilton are examples of this shift. In newsrooms today, doing more with less is an imperative.

At the Post, evolving technology has meant an evolving newsroom. Csanady joined the paper in winter 2015 to post content to the website. Yet, her proper title, web producer, doesn’t mean much in terms of her actual work. In fact, she writes a lot about politics for both print and the web. “It’s a new experiment for the Post to have someone who is on the web who is also sort of on a beat,” she says of the nimble newsroom and her informal specialty. Before the Post, Csanady worked for Queen’s Park Briefing—a subscription-based online political publication owned by the Toronto Star—covering the Ontario legislature for over two years. She then moved to Postmedia’s Canada.com in late summer 2014 before landing a spot at the Post. “I was fortunate that Queen’s Park was a specialty—and that the paper had a hole. I am essentially the Queen’s Park person, but without any formal title behind it.”

Bopping between the legislature and the Post’s headquarters, the 28-year-old reporter doesn’t have a typical day at work. She often files stories for the web before writing a slightly different version for print. The notion of quickly publishing information online is a massive shift from the traditional model, where reporters had more time to file stories for the next day’s paper. Csanady’s work is a good example of how reporters can do web-first journalism and then develop a version better suited to print. “Some people who have been in the industry for a long time still think filing everything at 7 p.m. is a good thing,” she says. “But when you look at web traffic, it always spikes at noon.”

Ellwand and Csanady’s situations extend to more experienced reporters as well. “The days of 20 or 30 beats being posted and having all these individual reporters on them are gone,” says veteran Vancouver Sun crime reporter Kim Bolan. “We all need to be more flexible with our resources.”

An employee of the Sun since 1984, Bolan has seen the newsroom shrink and beats come and go. Her work has won numerous awards, including the National Newspaper Award for beat reporting in 2015. Her fearless investigative crime reporting has brought her death threats, and she’s even taken security measures to maintain her safety. But none of this has stopped her, and because the Sun currently doesn’t have an assigned court reporter, she and legal affairs columnist Ian Mulgrew collectively cover court stories. The paper doesn’t put official titles under reporters’ bylines, but people take on beats informally. “We had a period several years ago when we didn’t have formal beats,” Bolan says. “But reporters often develop an interest or expertise in a certain area.”

Despite the evident shift in personnel structure, Hamilton Spectator managing editor Jim Poling says newsrooms have changed because the way we consume information has changed. He’s been at the Spec for 29 years and says the new ways readers access information come with an evolution in how newsrooms cover their communities. “It is too easy to say we don’t have beats because newsrooms have fewer staff,” he says. “There’s some truth in that, but that’s not the sum total of what’s going on.”

The Spec’s traditional police reporters used to visit precincts, where they attended regular media briefings and worked with staff sergeants to pick out prime stories. Today, because officials tend to cite privacy reasons for limiting the release of once readily available information, the relationship between cops and journalists has changed. “We could look at the arrest sheets throughout the day,” says Poling, who has worked various beats over his career. “That’s unheard of now.”

News gathering techniques, such as using social media and the internet, have also altered the way journalists access information. “It helps reporters gather much more information quickly,” he says. “It doesn’t necessarily mean they will get the answers, but they’ll get the context.” That means developing leads, finding angles and spotting trends. And finally, some beats have vanished simply because general assignment reporters have swallowed them up. “Journalists should be broad-based,” Poling says, arguing that the loss of beats is not necessarily a bad thing. “To say ‘I only cover what’s within this box’ doesn’t work anymore.”

This makes sense given that budgets are so tight, yet when I was researching this story, many reporters cautioned me that the changing nature of beats doesn’t really apply to the Toronto Star. The Star is an example of a newspaper that maintains a strong beat structure, with most reporters sticking to a defined topic. Deputy city editor Julie Carl says beat reporters are important to the Star because their work reflects the Atkinson Principles, named after the paper’s influential former publisher Joseph E. Atkinson: social justice, civic engagement and workers’ rights are all important aspects of the paper’s mandate. Knowing what’s going on in the government and informing readers is crucial, Carl says, and beat reporters, with their expertise, can bring hard-to-access information to light. “Beat reporters don’t just know their topic,” she says. “They have formed relationships, which can get them to the very information we don’t even know exists.”

At the Star, the vast majority of reporters are assigned beats. Interns work general assignment, taking stories from the news desk. Star reporter Tess Kalinowski, along with The Globe and Mail’s Oliver Moore and the Post’s Kristine Owram, is one of the few full-time Toronto-based reporters covering transportation. Carl says beats like Kalinowski’s are important, because subjects like transit can be social equalizers, and readers are interested in issues that affect them. “We want to make life better for the average person,” Carl says. During her career, Kalinowski hasn’t seen many beats evaporate at the paper but has seen some evolve. They are shared more broadly today, especially with the paper extending its offerings from print to online to a tablet edition. As Kalinowski says, “No one person can do everything for all those platforms.”

Although she works in the ninth-largest city in Canada, 31-year-old Kelly Bennett is one of just three full- time reporters at CBC Hamilton. The digital publication also employs one producer and one executive producer. Bennett has worked as a general assignment reporter since moving to “the Hammer” in 2014, but she has also built a reputation for covering police carding. The informal beat grew out of an assignment to cover a local rally after police shot and killed Michael Brown, a young Black man in Ferguson, Missouri. That’s when she learned Toronto wasn’t the only Ontario city carding its citizens, and she began investigating the controversial police practice in Hamilton. “I just tugged on that thread, despite not having a beat,” she says. Her digging helped her become known for the subject while still working general assignment. “Though I would never have ‘Kelly Bennett, CBC Hamilton, police reporter’ on my email signature, I have been the person to unravel that.”

Bennett’s career began in 2006, when the then-22-year-old Canadian reporter started working at Voice of San Diego. The non-profit digital news organization tried to put reporters on beats where enterprise stories could blossom. Bennett’s initial beat was housing and economics, so she submerged herself in the topic. In 2006, she began writing about the local real estate market and, later, the subprime mortgage collapse of 2007 and 2008. “When I think about the stories that have defined my career, they often took longer than one day to do,” she says. Bennett maintains a long-term mindset in Hamilton, even though the newsroom isn’t conducive to working on investigative pieces since daily stories demand urgency. “General assignment reporters should think of the stories they are doing as possible investments towards a specialty.”

From a marketability perspective, Bennett says experience on a beat is a selling point. Csanady also thinks a niche helps emerging journalists get jobs, even if they’ll be expected to cover totally unrelated stories. Ellwand echoes this stance: “On the job, you can develop your area of interest and talk to your editors about how you’re interested in moving into something else.”

Although working a beat is a significant role for journalists, it shouldn’t come at the cost of fulfilling general assignment duties. “The expectation is not that you’ll take a few days and not file any- thing,” Bennett says. “That’s just not the way the model works.”

Later on that December afternoon, it’s minus 15 degrees outside, and Ellwand power walks from the Journal’s office to police headquarters in downtown Edmonton. It’s only about 20 minutes away, but the temperature drags out each step. She’s been on the job for eight hours, and her shift is over, but Ellwand is set to meet police inspector Regan James for a video interview at 3 p.m. The topic is the aftermath of last year’s mass shooting. James was the first officer on the bloody scene, making him a central character for Ellwand’s upcoming anniversary feature. Freelance videographer Topher Seguin sets up his camera while Ellwand preps her questions. Her story will run in the paper, but the video is for a special web component.

A grey-haired James enters the room in an impeccably pressed, short-sleeved white dress shirt, dark pants and a straight, black tie. He speaks with the same seriousness of his uniform—sharp and without blemish. “Domestic violence—it can reach epic proportions,” he says. Ellwand leans her left elbow onto the large boardroom table and asks James to walk her through the horrific events. “And what happened after that?” a focused Ellwand asks. James tells her about the blood, about the screams, about the crying and about the bodies. “By no means did those people deserve their fate in any way,” he says. “And certainly not the children.” As Ellwand pulls out powerful details for her piece, James is calm, despite the chilling story he tells. As he adjusts his tie, a tattoo on his left upper arm peeks out from under his shirt. He pauses. “You never forget these types of events,” he says. “They stay with you forever.”

After about 45 minutes, the interview winds down. Ellwand has learned some new details and is able to fact check her timeline. While packing up her notebook and thanking James for his time, she tells him about her victim whiteboard. “The names won’t come off.”

After her feature ran, Ellwand poured bleach on a large paper towel and erased the letters that made up the names. “It’s just empty and white, which feels foreboding,” Ellwand says. “One day it will be filled, probably after something horrific has happened. I’m sort of dreading that day.”

About the author

Laura Hensley is the departments editor for the spring 2016 issue of the Ryerson Review of Journalism.