“I have some difficult news to share with you today,” began Renato Zane, director of news at Omni. He had called his Toronto team of multilingual journalists to a meeting. None of them knew what it was about, but that morning in May 2015, many feared the worst. Somewhere in the newsroom, a phone rang steadily, unanswered.

Zane went on to announce that, after 35 years, Omni News was over. The channels would survive, but the newscasts that had become staples of daily life in so many immigrant households would not. After going over details of the termination, Zane gestured to a photo of himself taped to the wall—a photocopy of his original employee ID, taken more than 30 years earlier. He briefly reminisced about his time with the broadcaster and thanked his employees for their hard work and dedication to ethnic journalism.

Then came the layoffs. Of the nearly 50 people who came to the office that morning on the third floor of Rogers’s downtown broadcasting hub, only 10 would remain.

Before breaking off to meet with management about the details of her own termination, producer Laura D’Aprile spoke briefly with anchor Dino Cavalluzzo.

“So this is it, right?” he asked in a hushed voice.

“I hadn’t thought they would do that, but…” She trailed off. Cavalluzzo said good luck and headed toward his own meeting.

“Bocca lupo!” D’Aprile called after him, an Italian good-luck phrase that translates to “into the wolf’s mouth.”

Later that day, news team members returned from a union meeting above the Hard Rock Cafe across the street, many still brushing away tears, to find their key cards deactivated. They stood together, locked out of the place they had worked in for years, where they’d arrived that morning intent on putting together Omni’s summer lineup. Finally, a colleague let them in to retrieve their belongings.

The loss of Omni’s newscasts was something none of its journalists expected, but it was the culmination of a nearly decade-long decline for the ethnic network. After years of growth championed by Rogers president Ted Rogers, a new generation of management had all but wiped out Omni, severely diminishing the linguistic and cultural diversity of Canadian broadcast journalism. And, with TV news struggling to stay relevant for an increasingly online audience, this death may be the beginning of an industry-wide extinction.

When viewers recognize Cavalluzzo on the street, or at functions in his new capacity as business development manager for an event and hospitality company, they all ask the same question: “What happened?”

He was one of two long-time anchors, alongside Vincenzo Somma, for Omni’s Italian newscasts. Cavalluzzo had started in the sports department in 1988 and, as operations were trimmed and consolidated, ended up responsible for sports, entertainment and, occasionally, entire newscasts. His on-air persona as an affable sports guy, with hair cropped to a short buzz and eyes that seemed to always be smiling, complemented Somma’s more serious, authoritative delivery. Together, they were an institution in Toronto’s Italian community. “Every weeknight for years, at 8 p.m., always at the same time,” says Cavalluzzo, “people would tune in.”

Omni was founded in Toronto in 1978 by Dan Iannuzzi, an enterprising Italian-Canadian journalist who originally named the station CFMT-TV, for Canada’s First Multilingual Television. It soon gained an audience among the city’s large and growing immigrant population.

For immigrant communities, the appeal of Omni’s journalism was twofold. First, it offered coverage of their cultures and countries of origin that went deeper than mainstream outlets did. It assumed a higher level of knowledge about other countries than programming meant for a Canadian-born audience.

Second, Omni succeeded in precisely the opposite way with distinctly local issues, from elections to garbage collection schedules. The coverage assumed minimal foundational knowledge and took on an educational role for those new to Canadian life. Doug Cheng, former managing editor of Omni B.C. Cantonese, says elections are the best example of how the network reported differently. “In China, you can’t vote nationally—these are people who may never have voted before. So it’s important to report to them about where the parties stand, but also to drive home the privilege of voting and why they should exercise it.”

During the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, Omni informed foreign-language households about how to protect themselves. For viewers who spoke no English, these newscasts were essential. As Rinaldo Boni, the network’s union vice president, notes: in some cases, being informed in time can be a matter of life or death.

Despite playing a vital role in Canada’s multicultural society, ethnic television proved unprofitable from the beginning. By 1986, Iannuzzi had lost nearly $10 million on CFMT and sold majority ownership of the station to Rogers—then a growing media empire-to-be.

Against all advice from company insiders, who were unwilling to look past the station’s niche market and near-bankruptcy, Ted Rogers invested in CFMT, affectionately dubbing it “The Little Engine that Could.” As the first television station under his passionate, business-savvy leadership, CFMT thrived.

To solve Iannuzzi’s problem of funding inherently unprofitable ethnic programming, Rogers negotiated with the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) for the right to broadcast American reruns and syndicated programs during prime time. These included popular shows such as Jeopardy and The Simpsons.

This lucrative programming supported the rest, keeping the station profitable for decades. “I insisted that Omni not become a social project of Rogers—that it become a legitimate, self-financing business,” says Leslie Sole, a former network vice-president who became CEO of Rogers Television. “That’s the only way we could prove that media in different languages aren’t just charming. They’re good business, and they’re good for the Canada that was being built.”

In 2002, Rogers was granted a second ethnic licence in Toronto. CFMT relaunched as Omni.1, covering European and South-American languages, and the new station, named Omni.2, covered pan-Asian languages.

In order to make its application for Omni.2 more palatable to the CRTC, Rogers set up the “Omni Fund”—$50 million to support various ethnic broadcasting initiatives, such as documentary programming by independent producers, public service announcements and dramatized series.

Critics argued that a second channel gave Rogers an uneven share of the ethnic market in Toronto, preventing smaller, independent foreign-language media from prospering. But while that may have been the case, the CRTC saw little harm in allowing Rogers a near-monopoly, as long as it committed its vast resources to advancing the cause of multiculturalism through journalism. By 2006, Chinese, Italian and Indian viewers—three principal chunks of Omni’s audience—each made up approximately 10 percent of Toronto’s population.

In 2007, Rogers purchased five City TV stations across Canada, including its first English-language, over-the-air broadcast station in Toronto. Soon, Omni was no longer a priority. The CRTC is strict about who can obtain free over-the-air broadcast licences such as Omni’s and City’s, which don’t require cable subscriptions, reach a broader audience and are more attractive to advertisers.

Had it not been for Omni.1 and Omni.2’s ethnic mandates, dividing languages between stations, Rogers would never have been able to get two licences in the same market—never mind the largest market in the country. Now, it had three.

The potential ad revenue Rogers could generate with three broadcast licences in the Greater Toronto Area was massive, but it was dampened by the fact that two of the three stations were restricted to two-thirds foreign-language content. D’Aprile says Rogers’s purchase of City created problems for Omni and that, increasingly, company management viewed the network’s ethnic mandate as a restriction rather than a responsibility.

Then, in December 2008, Ted Rogers died of congestive heart failure at the age of 75. His funeral at St. James Cathedral, on a rainy day in Toronto, was a sombre gathering of the country’s most powerful politicians and business leaders, from Stephen Harper to Galen Weston. And while Canada mourned one of its most successful entrepreneurs, Omni had lost its protector.

“‘The best is yet to come,’” said Rogers’s only son, Edward Rogers III, toward the end of the eulogy, echoing Ted’s beloved slogan. “With him gone, it’s hard to think how this can now still be the case.”

The last time production director Nick Christoforou felt optimistic about Omni Toronto’s future was in 2009. That year, the stations moved into the former Olympic Spirit Toronto building, constructed as part of Toronto’s unsuccessful bid for the 2008 summer games. The main floor editing facilities were sprawling, state-of-the-art suites that promised added production value, and a new location in the heart of downtown meant increased visibility for the Omni brand.

But as they settled into their new workplace, Christoforou and his colleagues had to work around increasing restrictions on their budgets, staff and equipment. Managers were under pressure to cut costs, and, as a result, Omni would produce less original reporting. One documentary, on Greek Easter traditions, was made almost entirely with recycled footage from television programs in Greece that had sharing agreements with Omni. Every ethnic community in the network borrowed from its homeland, Christoforou says.

Now that Omni was sharing space with City, an inferiority complex developed. Budgets were lower than those at City, which employees believed was due to lower viewership and smaller potential audiences. Several former Omni journalists describe feeling like second-class Rogers employees. The main reason they put up with it was the sense that, for foreign-language reporters in Canada, there was nowhere else to go. “No ethnic media would pay us better than Rogers—this has to be said,” says former producer Patricia Almeida. “But it was clear that we were not important to the company.”

At a town hall meeting toward the end of 2011, shortly before Almeida was laid off, both City and Omni employees gathered in a boardroom. Partway through, a City producer asked when his station was getting its helicopter. (It never got one.) The Omni team, who worked for a station that could barely afford to pay reporters, looked at one another, bewildered. Almeida says, “It was like we were talking about different universes.”

By 2012, the “Omni Fund” had expired. Much of the reporting for ethnic programs was done by students, volunteers and new immigrants freelancing for Omni who were paid between $50 and $150 per story. Production values declined as editors watched their resources gradually erode. Ad revenues for Omni were also plummeting. Rogers salespeople operated on commission and thus had an incentive to sell the more profitable time slots on English-language City.

Even before the move to Olympic Spirit Toronto, Omni journalists were overworked. Late one night, around 11 p.m., Christoforou sat in a computer screen-lit editing suite with a fellow producer. He was helping her piece together a story in post-production, and she was becoming increasingly frustrated—segments weren’t lining up, and her reporter couldn’t come in so late to help. Suddenly, she turned to him and said, “You know what, Nick? They’re taking advantage of us.”

The first major cuts fell on the diversity department, the other half of Omni Toronto: a team of journalists and producers from around the world in charge of putting together documentary programming in nearly 30 languages.

One night in June 2012, diversity producers received an email telling them to come in the next day and meet with their managers. Everyone knew what that meant. Omni’s diversity department had just succeeded, less than a year earlier, in unionizing. Almeida recalls managers making it clear in a meeting that they didn’t want her department to join the union, primarily because they couldn’t afford to pay union wages.

Still, she supported unionization even if it meant losing her job and calls it a point of principle. “We were doing the same jobs as people at City, and we were making a lot less money—less security, less everything,” says Almeida. “Because we were catering to a less profitable immigrant audience, we were not treated by the company in the same way. We thought that was extremely unfair.”

When contacted for comment on the role of unionization in the diversity department cuts, Colette Watson, vice-president of television and operations, replied, “These allegations are completely false…We need to continue to adapt to position us for continued success and growth. This was not an easy decision, but was right for our business longterm.”

Omni’s diversity department disappeared, but newscasts carried on with dwindling resources until last May. Boni still remembers watching his last Omni newscast the evening before the cuts—a Wednesday night. Vincenzo Somma signed off, saying in Italian, “Goodnight, I’ll see you tomorrow.”

“Tomorrow came,” Boni says sadly, “but the news didn’t.”

Daily newscasts are the core programming for any free over-the-air television station in Canada. But if Omni needed newscasts to justify its valuable broadcast licences, how could it justify losing them?

Daily newscasts are the core programming for any free over-the-air television station in Canada. But if Omni needed newscasts to justify its valuable broadcast licences, how could it justify losing them?

In June 2015, Rogers Media president Keith Pelley—along with Watson and Susan Wheeler, vice-president regulatory—appeared before the House of Commons’s standing committee on Canadian heritage to answer questions about the end of Omni News. From a ring of long tables in the parliamentary chamber, MPs grilled Pelley about the cuts. They quoted angry constituents; statements on Rogers’s commitment to local ethnic programming from Omni’s 2014 licence renewal (many of which the company has reiterated even since killing the newscasts); and a comment from Pelley on the obligation of corporations to support an informed citizenry when broadcasting on public airwaves.

For decades, free over-the-air stations have tolerated the financial obstacles inherent in producing journalism as part of an unwritten contract with the public. But as economic pressure makes this commitment less and less sustainable, broadcasters are looking for ways out.

In Omni’s most recent licence renewal hearing, Rogers requested a range of amendments that included removing percentage restrictions for programming in non-official languages and lowering the required hours of local programming, a category that includes newscasts. The majority of these requests were denied. “Advertising on conventional television is declining at a torrid pace,” Pelley told the MPs, unwaveringly disagreeing with each objection to the local programming cuts. “This isn’t just a couple of years—this isn’t cyclical—this is a structural change. And unfortunately, Omni, as the smallest and most niche player in the market, feels the pain.”

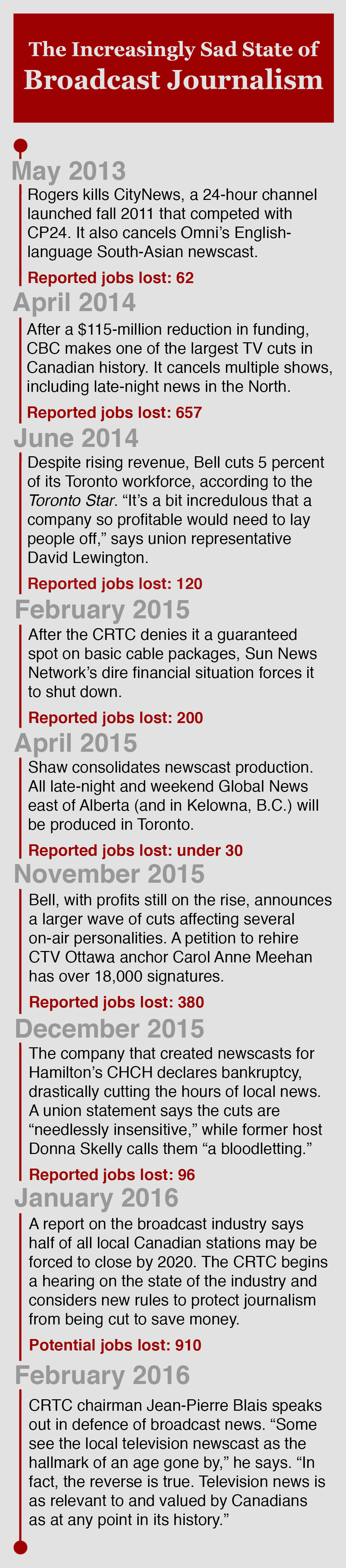

Developments since the Omni cuts suggest Pelley was right about the state of his industry. Last December, Hamilton’s CHCH TV filed for bankruptcy and laid off 167 employees, although 81 were offered deals that would let them produce content for the station through an outside company. CHCH also cut back its newscasts.

And in November, Bell Media announced its intentions to cut 380 positions, mainly in production and editorial, and cancelled TSN’s Off the Record. It’s not unreasonable to predict that Bell may also lop off entire newscasts in the years to come.

If Rogers’s financial woes and the drastic measures they inspire are representative of the television industry—one struggling, like others, to remain relevant in an online era—then the death of Omni News could be the beginning of something bigger, an unfortunate early demise in the decline of broadcast journalism. But Omni’s weren’t just any newscasts. They carried cultural heft and a message about Canada being welcoming and accommodating to newcomers—an immigrant country, rather than somewhere non-English speakers are forced to assimilate or be left in the dark.

Omni News produced the only professional-quality, widely available, freely accessible foreign-language broadcast journalism in Canada, but that significance was lost on those who controlled the network. “The new management didn’t know what they owned, and they didn’t understand what they were cutting,” says Sole, a former Rogers Media CEO. “The loss of newscasts was the loss of Omni. It isn’t Omni anymore.”

Now, Omni’s ethnic journalism comes in one form: a series of magazine-style, foreign-language current affairs shows. These are cheaper to produce than the cancelled newscasts and involve little original reporting. Watson urges viewers to give these new programs a chance, saying, “They won’t be disappointed with the depth of local issues they explore.”

Current affairs shows certainly have journalistic value, but what they offer in depth, they lack in timeliness and range. Ideally, these shows work in conjunction with newscasts. First, reporters present the news, clearly and without comment, and then guest experts can discuss and analyze it. Without newscasts providing the first half of the equation, it’s difficult for current affairs programs to stand on their own.

In the months following last year’s cuts at Omni, the CRTC deliberated on whether or not Omni could retain its licence without broadcasting daily newscasts. Several community organizations lobbied the federal broadcast regulator, writing letters that called for either the restoration of multilingual newscasts or revoking the licence.

The loss of news is made worse by a CRTC limit of “one over-the-air television station in a given language in the same market.” According to Stephen Hawkins, president of the local union for Omni in Vancouver, Rogers is “sitting on” its ethnic licence. By cancelling the news, the company is not only depriving Canadians of Omni, it’s depriving Vancouver, Calgary, Edmonton and Toronto of any freely accessible multilingual news.

In response to the letters, the CRTC declined to take action at all. Forcing Rogers to reinstate ethnic newscasts was beyond its jurisdiction, it claimed. And revoking the licence would be unfair given that, because of the unwritten nature of the social contract for broadcasters to support journalists, Rogers was technically not in violation of its licence conditions. This weak response further upset immigrant Canadians.

While many people, from multilingual journalists to community organizations to viewers, are angered by the loss of the news, Cavalluzzo simply sounds sad. The former anchor knows what he would have said to his audience, had management given him the chance to say it.

He would have explained that this was the end, it wasn’t what he wanted and it was beyond the news team’s control. He would have said thanks. “Our viewers deserved an explanation,” he says, “and we wanted to say goodbye.”

About the author

Jonah Brunet is copy and display editor for the Spring 2016 issue of the Ryerson Review of Journalism.

Such a pity. I remember with pleasure the years of channel 47 before and CFMT later . Best wishes to all my friends / colleagues of the past . Good luck everyone. From Florence , Stefano Di Perna for CFMT TV