“Journalism is about relationships,” says Joey Coleman. And, walking with him on a sunny day through downtown Hamilton, I’m beginning to see what he means. At Dr. Disc record store, he stops to chat with owner Mark Furukawa—Coleman’s having issues with the sound equipment he uses to live stream council meetings at city hall. Furukawa refers to the indie journalist as “a unique animal,” lamenting that there aren’t more like him. Later, we stop at a bakery on King William Street, where the woman behind the counter asks if Coleman will have the usual (two oatmeal-raisin cookies). He does. On our way out, a fellow customer calls after him: “Give ’em hell, Joey!”

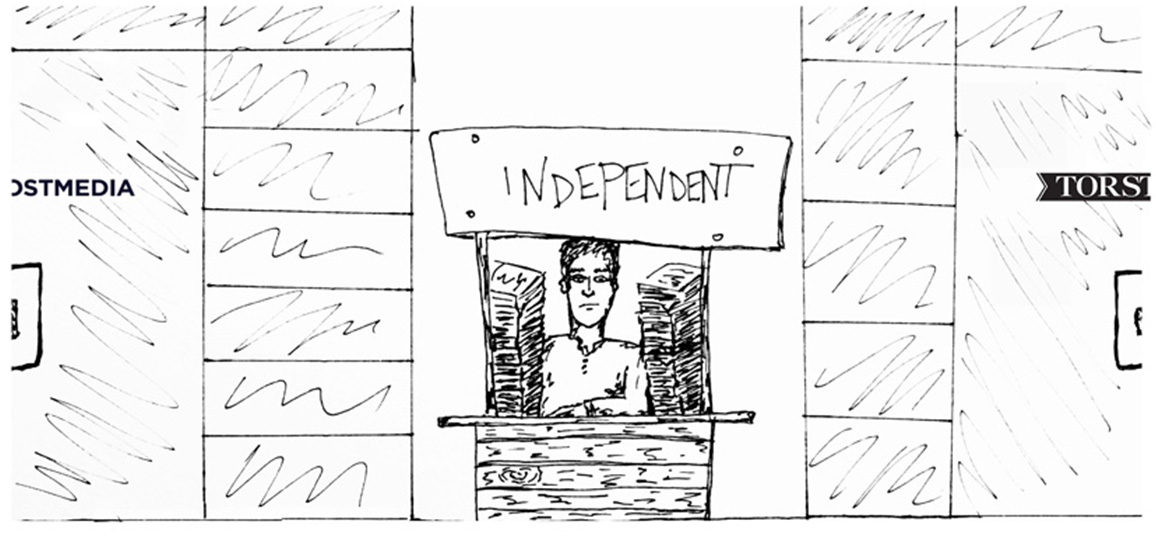

Since starting The Public Record—a one-person news site featuring live-streamed city council meetings alongside written news and analysis—Coleman has become a fixture in his community. But, despite Furukawa’s praise, his situation isn’t unique. Or necessarily ideal. Though independent reporting offers unparalleled freedom and editorial control, it’s certainly the more difficult path, littered with challenges not faced by traditionally employed journalists or even freelancers working for established brands. As Coleman quickly discovered, it doesn’t always pay to work alone.

One-person newsrooms are nothing new, but as traditional newspapers increasingly consolidate under the ownership of large media corporations, independent journalism has taken on new meanings. For Sean Holman, who founded Public Eye in 2003 to cover B.C. provincial politics, it meant keeping his government transparent through investigative reporting. For Gagandeep Ghuman, who founded The Squamish Reporter in B.C., it meant a closer relationship to readers.

Coleman’s own self-described mission to “find a new model to sustain local journalism” in Hamilton began in 2012. He bemoans the lack of fellow reporters at city hall, but isn’t blaming anyone because the council meetings he attends religiously are, more often than not, mind-numbingly boring. “I wanted to go more in-depth on something that wasn’t profitable,” he says, adding that traditional newsrooms rarely allow reporters to choose what they cover.

Update: After this story appeared, the office of the mayor contacted the Review to contest Coleman’s statement that few other reporters regularly attend council meetings. According to Coleman, his work on The Public Record has encouraged more reporters to attend, but he stands by the claim that there is a lack of reporting at Hamilton City Hall.

To make a living reporting the unprofitable, Coleman turned to crowdfunding. He accepts donations via his website (which, at its peak, made $600 per month), but relies on heavily publicized Indiegogo campaigns every few years for the bulk of his funding.

The Public Record is a video archive of city council as well as a news site. Rather than raking in clicks and page views, Coleman hopes his online streams can empower neighbourhood associations and help Hamiltonians hold councillors to their word. And he doesn’t get discouraged by low viewership, which averages around 50 for most streams, because the freedom to be boring, and to choose what to cover based on community significance rather than widespread appeal, is an upside of independent journalism.

By the winter of 2014, Coleman’s watchdogging had irritated city councillors who thought he was deliberately looking for gaffes. Lloyd Ferguson, for example; he’s the ward 12 councillor and former chair of Hamilton’s accountability and transparency committee. One evening, while speaking with a fellow staff member on the second floor of city hall, Ferguson spotted Coleman nearby. Assuming the journalist was eavesdropping, Ferguson confronted him and, after some shouting, grabbed Coleman by the arm and shoved him away from the conversation.

After this incident, Coleman says he found himself facing a number of restrictions that made it difficult for him to do his work. (Ferguson refused to comment on the incident for this story.) He is currently not reporting from city hall, but intends to return in January under the oversight of the Ontario Ombudsman. That oversight, he hopes, will do what the backing of an established news organization does for other journalists.

Legal protection is one the most significant benefits independent journalists miss out on. “I needed to make sure everything I published was airtight,” says Holman, whose investigations at Public Eye often scrutinized B.C. politicians. “I couldn’t afford to take a risk.”

In 2011, financial strain forced Public Eye’s website, which was funded primarily through reader donations and advertising, to cease publishing. Despite over 6,000 investigative and enterprise stories, some of which led to the resignation of public officials and even changed laws, people were turned off from donating to Holman’s reporting due to its aggressive nature.

Funding remains one of the largest issues facing independent publications. The pressure to make money from journalism—a strain on even the largest newsrooms—can be crippling when applied to a single person. In a competitive news market, independent journalists need to offer something different, says Susan Harada, associate director of Carleton University’s School of Journalism and Communication and head of the journalism program. “When you look at someone like Sean Holman, he wasn’t competing against mainstream media,” she says. “He was providing something different.”

Ghuman, whose paper is profitable because of ads from local businesses, says independents can be better poised to attract readers than their corporate counterparts. A transparent, direct relationship makes for a stronger connection to the audience—which, for The Squamish Reporter, and especially for the crowdfunded Public Record, makes all the difference.

Despite considering it the worst experience of his career, Coleman’s struggles with city hall and the underdog narrative they created have garnered him more support than ever. Thanks to publicity from his forced hiatus, he expects his upcoming crowdfunding campaign to be the most successful since his first one in 2012, when he raised over $10,000 in two months. “I’ve been really lucky,” he says.

But Coleman’s financial situation remains precarious, his luck vulnerable to running out. He estimates his expenses are $2,500 per month—including camera batteries, software licensing fees, travel costs, a rented room in a friend’s house and a lifestyle he calls student-like by necessity. Walking with Coleman through downtown, listening to him go on, ever optimistic, about the future of The Public Record, I can’t help wondering how long it will be before he hits the same financial wall as Holman.

“Maybe I can find a way to make local journalism work,” Coleman says, hopeful even while describing the mounting economic pressure on both his one-man newsroom and the larger industry. “History is full of economic disruptions that lead to better ways of doing things.”

Previous versions of this story incorrectly stated that Coleman’s media credentials had been revoked and that he was restricted from live-streaming council and committee meetings. Hamilton City Hall does not accredit journalists, and Coleman has not been formally restricted or banned from live-streaming either council or committee meetings. Additionally, previous versions of this story stated that the City of Hamilton contacted the Review, occasioning an update to the published story. In fact, it was the office of the mayor. The Review regrets the errors.

About the author

Jonah Brunet is copy and display editor for the Spring 2016 issue of the Ryerson Review of Journalism.