When Solomon Israel took a seat at his desk in the Winnipeg Free Press newsroom on a balmy morning in the summer of 2017, he probably felt everyone staring.

“That must be the weed guy,” I whispered to a fellow reporting intern.

In the Free Press newsroom, journalists often leave, but rarely, until recently, does fresh blood arrive. In 2010, the paper had about 100 editorial staff on any given newsday. Then staff started to dwindle as print media declined. Some veteran journalists retired, others left for new opportunities, and a couple quit the profession altogether. By 2017, the once-robust Free Press editorial staff had been reduced by a third.

So when “the weed guy” arrived, those still hanging around couldn’t help but gawk. If someone had suggested any major Canadian paper—let alone the 145-year-old Freep—would establish a dedicated cannabis beat a few years ago, they might have been accused of being high themselves.

Everything changed on April 13, 2017, when the Trudeau government unveiled legislation to legalize and regulate recreational cannabis, nationwide, by the following July. This would make Canada the second country in the world, after Uruguay, to federally regulate recreational weed. The announcement caused widespread anxiety and confusion: What about the children? Will people be driving high on the Trans-Canada Highway? Will my co-workers be going outside for a new kind of smoke break?

While the prospect of legalization had some Canadians seeing red, many others were seeing nothing but green. Canada’s agriculture, biotechnology, and healthcare industries were positioning themselves for legalization long before Trudeau’s announcement, hoping to cash in on the impending cannabis boom. Now, Canada’s struggling journalism industry is too, and publications are hoping not to be left in the dust.

At one point, marijuana only seemed to grace Canadian news pages when stoners gathered to smoke on 4/20, but as provinces began rolling out distribution plans, and as the number of licensed producers increased, cannabis stories slowly moved from pot busts to business boons. In October 2016, the National Post ran a national series called “O Cannabis,” an in-depth special section. When The Globe and Mail launched its redesigned paper in December 2017, an investigation about personal grow operations appeared above the fold on the front page, and on the next page was a report about the cannabis bill. In a matter of months, cannabis had gone from a faint whisper to an unavoidable conversation.

Just over a month after Trudeau’s government introduced the Cannabis Act, Paul Samyn, the 53-year-old editor of the Free Press, announced his intention to start a growing operation of his own. “We’re looking to hire a reporter to lead our cannabis coverage as Canada moves to legalize pot,” he tweeted, along with a link to a job announcement. “Send us your resume.”

Samyn said he needed to hire someone with “a sophisticated palate” and expertise in the Canadian cannabis industry. It’s fair to say it was the first time the paper ever hired someone based on their familiarity with an illegal substance. Still, Samyn wasn’t looking for a stoner. Dozens of responses to Samyn’s tweet made light of the idea of a cannabis reporter in Winnipeg, but he didn’t mind—more than 40 resumes flew into his mailbox. It was clear to Samyn, who’s been working at the Free Press since 1988, that he’d tapped a market that journalists were eager to cover. “We are now in a situation where the narrative [about cannabis] that has been part and parcel of newspapers and media everywhere in Canada is changing,” Samyn said in his office in October. “And it’s changing very fast.”

While traditional publications have mostly covered marijuana from a political or business perspective, Samyn has a savvy vision of a Free Press vertical becoming a national, and even international, hub for cannabis journalism, featuring coverage ranging from legislation breakdowns to consumer reporting.

The Free Press’s only local competitors are television and radio stations, the Winnipeg Sun, and the provincial Canadian Press correspondent. To cover marijuana, they’re going up against online mainstays like Vice and BuzzFeed; established weed publications like Cannabis Culture and High Times; and dozens of digital start-ups like Lift, Leafly, and the Business of Cannabis (B of C). B of C is a site launched in 2017 by Reva Seth, a respected Toronto lawyer who served as a policy advisor on the 2015 Trudeau campaign, and Jay Rosenthal, who hopes to produce original analysis and news, as well as ready-made sponsored content to run in major publications in Canada.

“The mainstream media hasn’t been getting a full glimpse of the industry,” Rosenthal says. “That’s what we’re trying to give.”

The Free Press has its work cut out for it if it hopes to cut through the haze and earn the national audience Samyn seeks. “This wasn’t a job opportunity that meant someone was going to sit in the back of the office with a bong every day,” Samyn explains. “And if that’s what people thought this was about, they are sorely mistaken.”

Nobody’s quite sure why marijuana was even made illegal in Canada in 1923. In her 2006 book, Jailed for Possession: Illegal Drug Use, Regulation and Power in Canada, 1920-1961, University of Guelph professor Catherine Carstairs writes that few Canadians of the era used cannabis, whose psychoactive compound, tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC, interacts with neural receptors to elicit chemical responses ranging from euphoria to paranoia. Some historians and activists point to Emily Murphy, a Canadian judge and suffragette (with distinctly racist views), as the bell-ringer for criminalization.

Cannabis was hardly an issue at the time, yet “reefer madness” set in, and the national press covered marijuana hysterically. A 1937 Globe and Mail report noted that while the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) didn’t consider cannabis (“the narcotic evil”) to be a national issue, the Mounties were gravely concerned about the green menace. “[Marijuana] has been known to turn quiet, respectable youths into raving murderers, seeking victims to satisfy their delusions,” the Globe report concluded. In 2017, former RCMP deputy commissioner Raf Souccar, ex-Toronto fire chief William Stewart, and Julian Fantino, the former commissioner of the Ontario Provincial Police, all joined forces on the executive board of Aleafia, a medical cannabis therapy network. Two years earlier, Fantino had tweeted, “I am completely opposed to the legalization of marijuana.” Now, he’s the executive chairman of a cannabis company. What a difference 80 years makes.

The Arcview Group, a U.S.-based cannabis market research firm, reported that in 2016, North American marijuana sales totalled $6.7 billion; a January 2018 Statistics Canada report estimated that about 4.9 million Canadians between the ages of 15 and 64 spent $5.7 billion on cannabis for medical and non-medical purposes in 2017; and a 2016 Deloitte report posited that the Canadian cannabis industry could stimulate as much as $23 billion in economic activity each year—roughly equal to the Canadian forestry industry’s economic injection in 2016.

Although those projections are lofty, Canadian Press business editor Sunny Freeman, 35, says they could be much higher, or way lower.“Nobody knows exactly how big it is because nobody knows how many people out there already consume it,” adds Freeman, who started covering marijuana in 2013 while at The Huffington Post. In 2016, she joined the Financial Post as its resources reporter. Cannabis came up there so often that Freeman and her editor decided it would be appropriate to expand her beat description to mining and marijuana. “It was an avalanche of coverage.”

Freeman reported on the business of cannabis, its implications to health and public safety, and policy implications as they arose. “It touches every single beat,” she says. “It was exciting then, and it’s even more exciting now.” The medical industry is racing to legitimize cannabis as a healthcare option, as seen in the evolution of public and institutional opinion on the subject, while entrepreneurs are developing ancillary businesses as public intrigue rises. “Canada really does have a chance to be a global first mover in the marijuana industry,” Freeman adds.

In the United States, The Denver Post hired its first marijuana editor and launched The Cannabist, a weed website with news, reviews, and features in December 2013, just a month before Colorado became the first state to legalize weed. The San Francisco Chronicle hired a cannabis editor and launched Green State, a weed website. The Boston Globe began offering a weekly marijuana newsletter, succinctly titled “This Week in Weed,” offering the chance to “witness the birth of the marijuana industry in Massachusetts.” In January 2018, The Guardian in the United Kingdom launched “High Time,” a “cannabis column for grownups,” and three weeks later, the Associated Press created a 10-person national beat group to cover legalization and regulation.

Twenty-nine other states have since followed Colorado’s lead, although cannabis is still illegal at the federal level in the United States. In January 2018, shortly after California legalized, Attorney General Jeff Sessions rescinded Obama-era policies, suggesting a move toward federal intervention in state legalization efforts. Sessions’s decision created a furor in the cannabis community, and flew in the face of American opinion: 64 percent of Americans favour legalization, according to an October 2017 Gallup poll.

Predictably, Canadian marijuana stocks took a dip, but many Canadian insiders saw the American regression as an opportunity for growth. “I get calls every week from Americans who want to invest in the company,” Gary Symons, the director of communications for Winnipeg’s Delta 9 Biotech Inc., told The Tyee. “Investors are going to look for a safe haven where they can invest in the fastest-growing business in the world.”

On November 21, at exactly 4:20 p.m., The Leaf—the Free Press weed vertical—unfurled. The site’s logo—a white Cannabis sativa leaf superimposed on a red maple leaf—is equal parts patriotic and hydroponic. While the Free Press is paywalled, The Leaf is free, which Samyn hopes will attract “eyeballs” from around the world. The site runs wire copy in its “World News” section, but for the most part, The Leaf is Solomon Israel’s journalistic playground.

Israel tried to establish a similar beat in spring 2017 while working as a web business writer at CBC in Toronto, but says the public broadcaster wouldn’t commit to a dedicated weed reporter. In June 2016, he built a bed into his 2005 Honda Element and drove to Colorado to report on how legalization affected the state, producing three web stories, two of which had accompanying short radio documentaries. It wasn’t a money-making trip, but it was a career-making one. Israel also produced a cannabis documentary, entitled Hashing it Out, at the end of 2017.

Israel found the cannabis industry fascinating, so when he arrived in Winnipeg, he already had an extensive list of story ideas. The first feature posted to The Leaf was an all-encompassing guide to deciding whether to cultivate marijuana at home. “So, you want to grow your own (legal) weed?” ran in the Saturday paper.

It’s a far cry from the experience of Vancouver’s alt-paper, the Georgia Straight. In 1969, its then-editor-in-chief, Dan McLeod, and former managing editor, Bob Cummings, ended up in provincial court over their cannabis growing guide, a front-page story that encouraged readers to “plant their seeds.” The Straight had already earned a notorious reputation. Vancouver mayor Tom Campbell called it a “filthy, perverted paper.” The paper, the Globe wrote, ran everything “from standard apartment-for-rent ads to appeals for sexual liaison.” In 1971, a Moosomin, Saskatchewan, schoolteacher was fired for letting Grade 9 students read the Straight. “The whole town is in an uproar,” the superintendent told the Globe.

For publishing the guide, McLeod and Cummings faced charges of counselling the cultivation of marijuana, a direct violation of the Narcotics Control Act. The charges were eventually dropped. Now, the Straight has a full-time cannabis editor, Amanda Siebert, who took on the role in July 2017. Siebert’s section publishes, on average, two stories per day, and there is no shortage of angles for her to tackle. “I have the opposite problem,” she says. “I have too many stories to write and not enough time.”

Siebert says she was made editor because coworkers noticed cannabis piqued her interest. “I’m open about it. I tell people I’m a cannabis user, and being open helps me get a better grasp on what I’m reporting on,” she says. “I eat, sleep and breathe cannabis.”

Israel wouldn’t go that far, but cannabis is on his mind 24/7. Within The Leaf’s first two weeks, Israel sent out the first edition of The Leaflet, a weekly newsletter; debuted a cannabis advice column, cheekily called “Dear Herb”; and published an interview with Israeli chemist Raphael Mechoulam, a member of the first team to isolate the chemical structure of THC. The site doesn’t run strain reviews, but Samyn isn’t ruling out a more consumer-based reporting strategy in the future, once cannabis becomes legalized.

Israel’s intended audience is larger than the Free Press’s, which, as of 2017, boasts the best reach (64 percent of Winnipeg adults) of any daily newspaper in a major Canadian city. He and Samyn hope to develop The Leaf into a hub for cannabis journalism, and audience engagement has been growing, Samyn says. Since The Leaf’s launch, its monthly traffic has grown by an average of 20 percent, with nearly 30 percent growth in unique visitors, says Wendy Sawatzky, Free Press associate editor. About 12 percent of readers are based in the U.S.

Advertisers are taking note. On The Leaf, the Free Press is charging about double the price for ads that it does on its regular digital platform, says Karen Buss, the paper’s director of ad sales; cannabis ad rates range from $45 to $60 per net CPM (cost per thousand). In Manitoba, the law about advertising cannabis is still somewhat unclear, but it’s expected to follow similar guidelines to tobacco—although nothing has been made official. So while Buss couldn’t run ads for the substance itself, she anticipated having a full slate of cannabis-related advertisements, from tear-proof bags, to leaf cutters and other accessories by January. But, she says in late February, the ads haven’t come in as quickly as she thought they would. Once legalization hits, however, she anticipates that even more companies will be looking for space to advertise. “I believe that it will increase the paper’s overall revenue,” she says.

While not every publication is creating weed verticals, there isn’t an editor in Canada unaware of readers’ interest in cannabis stories. Derek DeCloet, the editor of the Globe’s Report on Business, says that cannabis has moved ever higher on his list of topics of interest since Trudeau’s announcement in March 2017. DeCloet adds that the ROB’s cannabis coverage has seen a noticeable spike in readership, especially among investors.

Legalization, DeCloet observes, has driven up interest in publicly-traded cannabis companies, and during the fall of 2017, Globe reporter Christina Pellegrini began covering them essentially full-time. (DeCloet said she occasionally writes other stories as well.) Pellegrini had started covering the industry with zeal a few months prior. “At some point,” DeCloet says, “myself and the other editors went to her and said, ‘We need someone to cover marijuana full-time, and that person should be you.’” But DeCloet acknowledges that legalization has brought “more stories than any one reporter can do.

“You can expect to see many different reporters’ bylines on stories about cannabis,” he adds. “It’s a pretty big deal, what’s happening.”

Reporters at regional papers are boning up too. Jacquie Miller of the Ottawa Citizen has reported extensively on illegal dispensaries and policy, and has educated herself on the finer points of cannabis to deepen her reporting. “I don’t smoke it, though,” she says, laughing. “I’m a karate mom.”

Lauren Strapagiel, managing editor for BuzzFeed Canada, says her newsroom is too small to justify a full-time dedicated weed reporter. (She is one of two full-time editorial staff dedicated to Canadian news.) However, Justin Ling, a former Vice Canada editor, has been brought in to contribute roughly one story per week related to cannabis, among other topics. Strapagiel emphasizes how important covering overlooked topics—like the effects of cannabis policy on racialized and Indigenous people—will be moving forward. “There are a million angles on this story,” she says.

BuzzFeed Canada belongs to BuzzFeed’s international media network, and Strapagiel knows Canada’s legalization efforts will be of international interest. “The world is going to be looking at Canada to see how we tackle this,” she says, unsurprised that traditional publications are jockeying to cover cannabis. “They have to cover it. It’s a huge story that impacts everybody in the country.”

Adam Greenblatt, the Quebec brand manager of Canopy Growth Corp. (TSX:WEED), the largest publicly-traded licensed producer in the world, says he’s seen a major shift in news coverage of pot. Greenblatt co-founded Montreal’s first medical marijuana clinic, and ran for Parliament in 2004 at the age of 19, as a Marijuana Party representative. “I’ve seen it go from a being a fringe issue to a mainstream one,” Greenblatt adds. “The industry is, too.”

Companies that produce cannabis paraphernalia will seek places to advertise, and mainstream publications like The Leaf are going for the ad revenue. However, some websites, like Lift News have been writing about and reviewing cannabis products and strains for years.

When I first spoke to David Brown, then-editor-in-chief of Lift News, he was following exactly 420 people on Twitter, though it wasn’t clear whether it was social media serendipity or a marketing ploy. “Just to be silly, I guess,” he later confirmed.

In 2014, Brown’s business partner Tyler Sookochoff, founder of Lift, saw that legal cannabis sales were moving toward the web, so he and Brown decided to develop a community for online discussion to create a better-informed medical consumer. Lift features product reviews for weed strains, oils and weed accessories, and posts between 20 and 30 stories each month, which Brown says are non-partisan, along with sponsored content from cannabis companies.

Lift publishes strain reviews, detailed reports on provincial marijuana policy, and information about the growing stable of licensed producers.“It’s really kind of just grown organically,” he says. Lift currently has about 25 staff, including salespeople and marketers, and runs annual cannabis expos in Toronto and Vancouver. “It’s not strictly a media outlet by any means.”

Brown thinks legacy news companies adding cannabis beats will be essential toward understanding legalization and its impact. When reporters know the legislation and its regulations inside and out, they’ll ask more informed questions. “It’s a fascinating topic, and I’m excited to see more media companies invest in this beat,” he says.

The site caters to a small, but increasing, market of medical users, along with industry professionals, policy makers and non-medical consumers. Many cannabis industry insiders and journalists alike point to Brown as the go-to guy for in-depth looks at the Canadian marijuana industry, policy, and international law, rather than puns or jokes about cannabis.

“My goal is to make weed boring,” Brown says.

In January, Brown announced he was leaving Lift to join the federal government’s Cannabis Legalization and Regulation Secretariat, in the policy, legalization, and regulatory affairs commission. He’ll still be trying to make weed boring.

Replacing Brown is Kate Robertson, a graduate of Western University’s journalism school and former digital editor at Toronto’s NOW Magazine. Robertson, who openly uses cannabis, says Lift is expanding, adding managing and associate editors, as well as a content marketing professional to monetize the site’s news section.

Like Brown, Robertson stresses that Lift is objective. “When it comes to news, you have to give readers content that isn’t one-sided,” she says. “If there’s anything that’s been unfortunate about traditional cannabis publishing, it’s the shameless bias that’s made some of those websites unreasonable.”

Canadians need reliable reporting in order to understand the cannabis space, Robertson says.

Brown agrees. “I think that covering this topic is sort of a historic duty.”

A few minutes before the prime minister took his seat at Vice Canada’s Toronto headquarters for a town hall meeting about legalization, Patrick McGuire, the alt-media giant’s former head of content, stood with a smirk on his face and a two-foot-tall replica of a weed plant in his hand. It was over a week after the legalization announcement, so Vice, which since its 1994 launch has covered drug culture extensively, invited Justin Trudeau for a discussion with senior writer Manisha Krishnan, 30, about the “nuts and bolts” of the policy.

“I was hoping we could start with you telling us about the last time you smoked weed, and why was it the last time?” Krishnan asked to open the conversation.

“Um. You know, actually, one of the things is, my friends, my high school friends, everyone who’s known me a long time thinks it’s just really really funny that I’m the one in charge of legalizing marijuana,” Trudeau replied. “Because they know that I am the boringest partier when it comes to drugs of any type.” A number of years earlier, Trudeau continued, a joint was passed around at a party, and he “took a puff.” Across Krishnan’s face crept a grin.

Since starting her career in 2008 as a reporter and editor for North Vancouver’s North Shore News, Krishnan has bounced across the country, working for Maclean’s, the Calgary Herald and the Toronto Star. With a wealth of reporting experience, Krishnan has a deep understanding of what legalization will mean in various pockets of Canada.

The audience was comprised mostly of young people interested in hearing what Trudeau had to say. Zoe Dodd, a harm reduction worker, passionately pleaded for Trudeau to legalize all drugs to combat the opioid crisis. Malik Scott, a young Black man facing charges for possession of marijuana, asked the prime minister if he’d planned to pardon people like him once the law changed. In both matters, Trudeau was noncommittal.

Krishnan has several beats, but counts weed as one of them, as do many other Vice Canada reporters. “I think Vice has so much more weed literacy than any other outlet,” Krishnan says. “I think that our weed coverage is by far the best in the country.”

McGuire says Vice’s mandate for covering marijuana is all-encompassing, focusing on policy, economics, health, and culture, including the “human” side of the story. Yes, in 2016 Vice published an article titled “This Is What Happened When I Ate a Mega-Dosed $500 Weed Sundae.” But the media site has also consistently pushed out some of the most in-depth coverage of cannabis’s black market, harm-reduction efforts, and the industry’s dark underbelly.

A few days before The Leaf launched, for example, Krishnan published an extensive investigation into a national chain of dispensaries allegedly exploiting its workers. Krishnan spent six months reporting, and her story shed light on an industry that few Canadians understand as fully as she does. “Despite the fact that dispensaries have become ubiquitous in major Canadian cities, their inner workings largely remain a mystery,” she wrote.

Vice has the insight to ask intelligent questions of politicians, which Krishnan says all media should, even though some reporters still treat marijuana as a big, green bogeyman. When Ontario’s provincial government announced its plan to distribute weed through its liquor retail shops in October, Krishnan angled to ask Premier Kathleen Wynne a question. One reporter, Krishnan recalls, asked something along the lines of, “Is this stuff dangerous?” Krishnan found the question disingenuous. “I was just kind of rolling my eyes and thinking, ‘Are we still on this?’” Krishnan says. “It’s just such a Weed 101 understanding.”

“I don’t know that [journalists] are making mistakes as much as they’re just a bit late to the party,” McGuire says. “Think of your average Toronto Star reader or Toronto Life reader. The odds of them being directly affected by drug policy, I’d say, is pretty slim.”

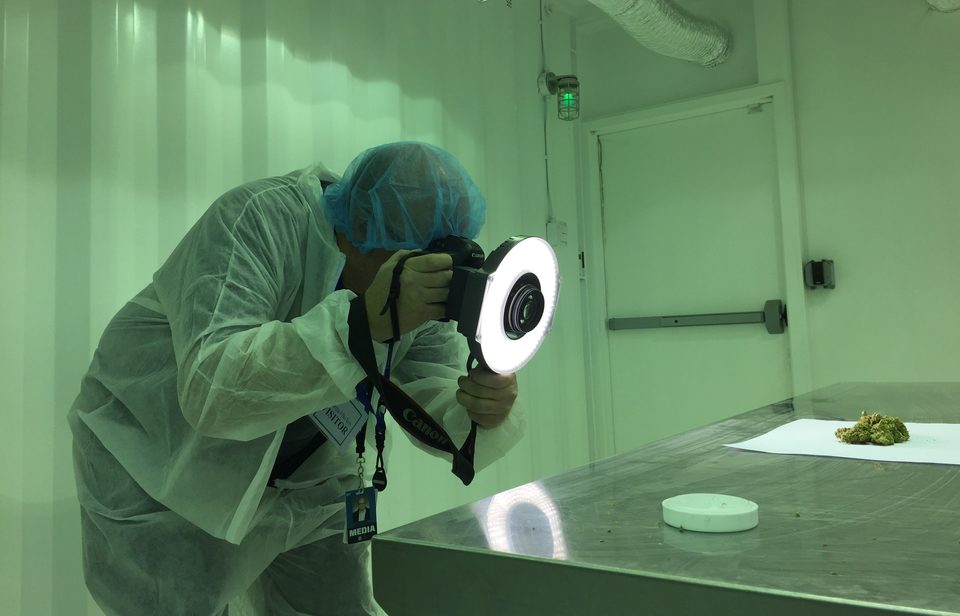

December 2017: Solomon Israel puts one hairnet on his head and another on his bushy brown beard before he walks into a production pod at Delta 9 Cannabis Inc.’s 7,432 square-metre medical cannabis production and distribution facility in Winnipeg’s Transcona neighbourhood. “I’m assuming there are no free samples for the press?” Israel asks Delta 9’s 27-year-old CEO John Arbuthnot, laughing as he walks in.

Wearing his hairnets, a mesh-like bodysuit, and a pair of blue latex booties over his slushy shoes, Israel, along with Free Press photojournalist Mike Deal, goes in for a tour—a rare opportunity to see the inner-workings of a potential industry titan, and to see its cultivars up close. Delta 9 is one of two licensed medical cannabis producers in Manitoba, and the only one with full licensing for cultivation and sale. In November, the company listed on the TSXV exchange with a private placement offering of eight million common shares. A few weeks later, Arbuthnot struck a deal to distribute Delta 9 product through Canopy’s Tweed Main Street online store, a network with over 60,000 members.

Deal, who photographed the facility some months before, is taken aback by its rapid expansion. “So much has changed,” he says.

Arbuthnot leads the pair throughout the vast complex, a nondescript, sheet-metal-covered building tucked neatly under the city’s nose. Despite the thousands of kilograms of cannabis being cultivated in over 15 specially-designed, odour-controlled growpods, Israel can’t smell a thing from the warehouse floor. Delta 9 was approved by Health Canada to add 143 more pods, but the company hopes to one day have 600. Between July 2018 and July 2019, Arbuthnot aims to open 30 retail shops across Manitoba, so long as it’s allowed under provincial regulations. “We’ve got a lot planned,” he told me, although Israel had already reported on all of that.

In the first pod, Israel and Deal get a look at Delta 9’s Super Lemon Haze, a strain that sells for $9 per gram. Justin Roy, the production supervisor, offers smell samples. “It’s got a real citrus scent,” he says as Israel takes a whiff. The tour proceeds to another pod, where juvenile plants grow under bright lights. Delta 9 currently produces about 2,000 kilograms of cannabis per year, but the company is aiming to increase to 17,000 by 2020.

As Delta 9 expands, other cannabis companies will too. According to Health Canada, there are currently 91 licensed medical cannabis producers in Canada, along with over 235,000 registered clients as of September 2017—a number that will only continue to climb. The number of medical practitioners providing documents for clients to access marijuana is increasing too.

Israel is at the centre of the boom, and he doesn’t think The Leaf’s stories will slow down anytime soon. As for his audience, Samyn isn’t concerned about a lack of interest from readers, even those who are nearing retirement age. “Last time I checked, they had weed at Woodstock,” he quips.

In the pod, Israel reaches a latex-covered hand toward a shelf to his left with dozens of tiny green plants. He lifts one up, exposing its roots. It’s like a hockey reporter getting a one-on-one interview with Wayne Gretzky. “That’s beautiful,” he says.

But Israel can’t stick around for too long. He has to go file his third story of the day.

Enlightening Up

A cannabis reporter’s dictionary

The language related to cannabis can be complicated, filled with acronyms, chemistry jargon, and legal terms. Here are 10 terms to help cut through the smoke:

ACMPR: Introduced in 2016, the Access to Cannabis for Medical Purposes Regulations is the federal set of guidelines outlining legal procedures regarding the distribution of, and access to, cannabis required for medical purposes.

LPs: Licenced cannabis producers are allowed to grow and/or sell marijuana issued under the ACMPR to the public. That includes dried or fresh marijuana, cannabis oils, or starting materials for consumers legally allowed to purchase it.

Dispensaries: Unlicenced storefront operations selling cannabis that are illegal under Canadian law. Their supply is grown by unlicenced growers and is not subject to testing or regulation. Canadian police frequently raid and shut down dispensaries.

The Grow: A reference to where cannabis is grown in geographical or spatial terms. “Where’s The Grow?” Indoors or outdoors? In Ontario or Alberta? If you don’t know, ask.

THC: Tetrahydrocannabinol is one of two active compounds in cannabis and the plant’s primary psychoactive component. THC acts on specific binding receptors to elicit the high feeling. The compound was first isolated in 1964 at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel.

CBD: Cannabidiol is a compound found in cannabis that doesn’t produce intoxicating effects when interacting with neural receptors. It’s often cited for its therapeutic applications, notably related to treating childhood epilepsy.

Cannabinoids: THC and CBD are both cannabinoids, plant-based compounds that interact with the human body to produce physiological effects.

Terpenes: Hydrocarbon compounds that produce distinctive scents that are produced by plants, including cannabis. Different terpenes produce unique aromas in different strains of cannabis.

Per Se Limit: In regard to drinking, the per se limit is .08—or 80 milligrams of alcohol per 100 millilitres of blood. Canadian provinces are currently devising per se limits regarding THC, although many have disputed the effectiveness of such a policy given the wide range of effects cannabis has.

The Black Market: Any cannabis business operating outside the ACMPR and other regulations. In certain areas, like Vancouver and Victoria, a “grey market” exists, containing both legal and illegal elements. Those cities have given business licences to storefronts that operate outside of the ACMPR’s purview.

About the author

Managing Print Editor, Ryerson Review of Journalism