Bill S-231, also known as the Journalistic Sources Protection Act, was passed into law on October 4. The news was celebrated nation-wide because—for the first time in Canadian history—both journalists and their sources will be protected from unwarranted searches. But while the law is a step in the right direction, Canada’s source protections fall short of protecting non-journalistic sources.

In a lot of cases, the anonymous sources protected under Bill S-231 are whistleblowers. Not all whistleblowers report their knowledge to journalists, which leaves a group of citizens unprotected by the law.

Whistleblowers—individuals who expose any form of illicit or illegal activity—often turn to journalists to shine light on issues or scandals risking financial and professional setbacks, as well as potential harassment and physical danger by sharing information. Until now, whistleblowers had virtually no legal protection in Canada.

“It is in no sense a perfect bill. It gets us a lot of the way there, but it does have a lot of deficiencies,” said Duncan Pike, a co-director at Canadian Journalists for Freedom of Expression (CJFE), who oversaw their nation-wide campaign for the bill. CJFE lobbied not only to push for the bill’s passage but also to improve upon its shortfalls—which they were unsuccessful in improving.

Among CJFE’s failed efforts was a push to broaden the definition of a “journalist” to include student reporters and part-time reporters. It also wanted the bill to protect non-anonymous yet sensitive sources, not only anonymous whistleblowers. Quebec Senator Claude Carignan, who introduced the bill, also made a strong case to protect whistleblowers as well as journalists.

Even with current changes, Canadian protections fall short. Serbia, one of the global leaders in whistleblower protection, passed the Protection of Whistleblowers law in 2015. This protects government and corporate employees from all retaliation when whistleblowing, bans any acts that prevent whistleblowing and fines organizations for failing to set up whistleblowing protection, according to a report by the Regional Anti-Corruption Initiative’s report.

Other countries with strong whistleblowing laws are Ireland, Australia, the U.K. and the U.S.

On April 15, 2007, the Canadian federal government implemented a law to protect whistleblowers and create a safe process to disclose wrongdoings in the public sector—the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act (PSDPA)—but freedom of expression advocates and industry experts say the law is both outdated and incomplete.

“It’s in complete shambles—it’s a farce,” said David Hutton, a senior fellow at the Centre for Free Expression (CFE) and former board chair and executive director of the Federal Accountability Initiative to Reform.

According to Transparency International—a non-governmental global organization which implements initiatives to fight corruption—for a whistleblowing law to be effective, it must protect the whistleblower against all forms of “retaliation and discrimination in the workplace.”

Progressive whistleblowing laws remove the burden of providing proof from the whistleblower; they remain anonymous so they are not liable for breaking confidentiality agreements.

When the 10-year-old PSDPA was initially put forward, but not yet passed, Hutton analyzed it and found many “serious problems.”

“We decided right then and there, this is not a good effort. This is just made to look like they’re doing something,” he said.

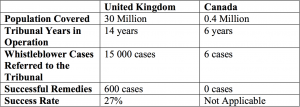

According to a review report of PSDA, written by Hutton and published by the CFE, the key shortcomings of the act was its fail to provide it’s purpose. One big issue with the process of investigating whistleblowing cases under the PSDA, according to Hutton, is its timeliness. Over 10 years, only seven complaints have been investigated and referred to the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Tribunal, and according to James Turke, the director of CFE, not one person has gone through the tribunal process and gone out compensated.

A whistleblowing case must be approved before it can be referred to the Tribunal, which is the only place the complaint can be remedied, and that process can take up to a year or more.

Newly established laws are also supposed to be reviewed every five years in order to make updates and improvements, but the federal government under Stephen Harper blocked examination and review of the system. When the Trudeau government came into power, PSDPA was sent into review in 2017.

Without a proper whistleblowing law in Canada, whistleblowers who do not reveal their findings to journalists will be left unprotected from pushback. For this reason, Sandy Boucher, a corporate investigator with experience working in both the private and public sectors, and a senior fellow at CFE, says S-231 is only improving a small component of freedom of expression in Canada.

“It’s just not in the central theme of where we need to be moving,” said Boucher. “We need to make a law that protects whistleblowers every day in every part of our country and whoever their employer is.”

About the author

Karoun Chahinian was the print production editor of the 2018 issue of the Ryerson Review of Journalism